Louis-Vincent Gave, CEO and co-founder of Gavekal Research, sees a dramatic paradigm shift playing out in the world economy. In this in-depth conversation, he explains how investors should position themselves for the future.

Louis-Vincent Gave is a master of the big picture. The co-founder of Hong Kong-based research boutique Gavekal is one of the most esteemed writers about geopolitical and macroeconomic developments and their impact on financial markets.

In this in-depth conversation with The Market NZZ, Mr. Gave shares his views on the Dollar, stock markets, oil and gold prices – and he explains why the United States are starting to act like a «sick emerging market».

This year’s debt buildup in the US has funded zero new productive investments. No roads, no airports, railroads, nothing: Louis Gave.

Mr Gave, 2020 has been a catalyst for some big shifts in the global investment environment. Looking into the future, what are the biggest topics for you?

I’ve spent most of my career in Asia, so my lens is fundamentally biased towards Asia. With that disclaimer, I would say this: When the Covid crisis started, the view in the West was that this would be China’s Chernobyl Moment. That they completely screwed up, which would eventually weaken the regime. Fast forward to today, and China comes out of this looking much better than most Western countries. If there is one big divergence in the world, it is this: In most Western countries, the population is angry at how their government dealt with the pandemic, either because they think the government did too much or too little. But in China, there is a feeling that there were two big crises in the past 15 years, the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and now Covid, and China in both cases came out ahead of the West. Most of Asia actually came out of this much better than the Western world.

What else do you see?

When I look at markets, there are three key prices in the world economy: Ten year Treasury yields, oil, and the Dollar. One year ago, yields were going down, oil was going down, and the Dollar was going up. Today, Treasury yields are going up, oil is going up, and the Dollar is going down. This is a huge reversal. When I see a market where interest rates are rising and the currency is falling, alarm bells go off.

Why?

This is what you would see in a sick emerging market. If you’re invested in, say, Indonesia, rising interest rates and a falling currency is a signal that investors are getting out, because they don’t like the policy setting there. Today, the US is starting to act like a sick emerging market. We even have a question mark over whether they have the ability to run a fair election. Suffice to say that at least 30% of Americans believe their election system is rigged. This is mindblowing.

What’s the policy setting investors don’t like in the US?

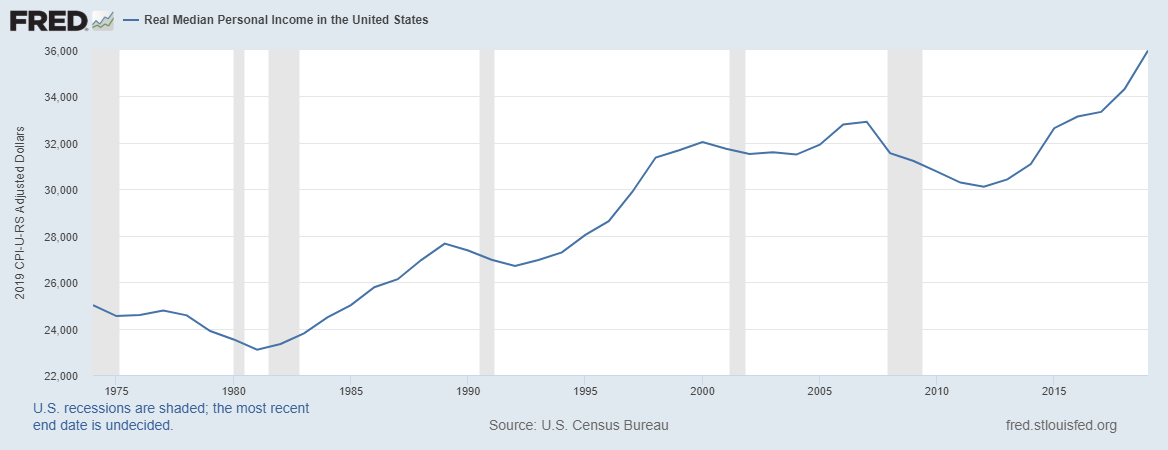

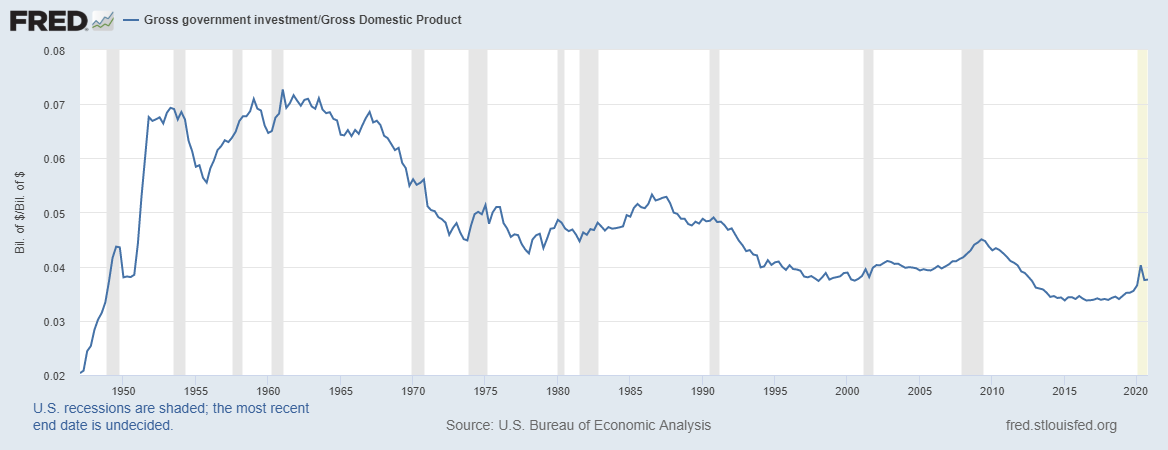

Government debt in the US has increased by more than $4 trillion this year, which adds up to $12,800 per person. This is a world record, but actually most Western governments have gone on a massive spending spree during this crisis. In a way, they’re using the playbook that China followed after 2008, when they allowed a massive increase in fiscal spending and monetary aggregates. Today, Beijing sits on its hands in terms of fiscal and monetary policy, while the West knows no limits.

They’re doing it to soften the blow of the pandemic. What’s wrong with that?

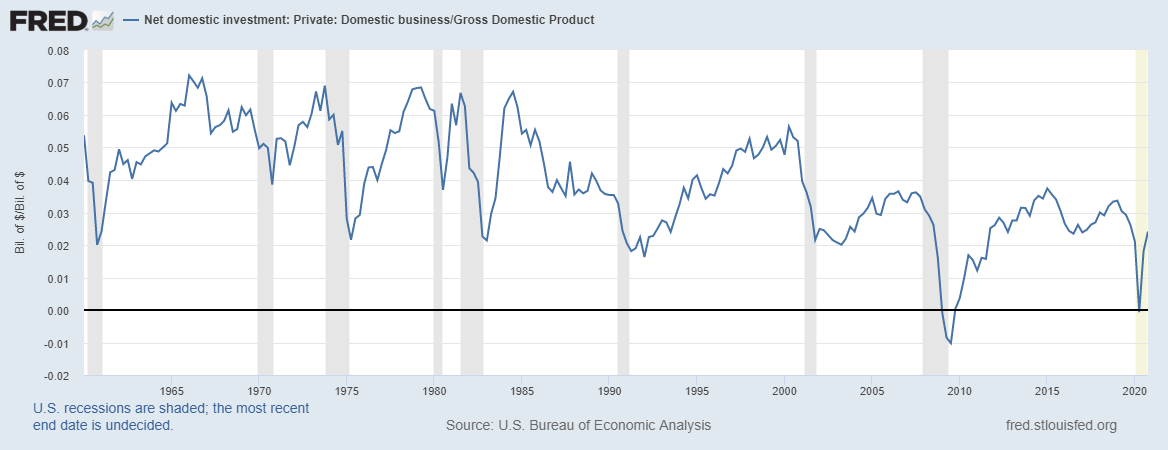

When China did this in 2008, they funded massive infrastructure projects: airports, railroads, roads, ports, you name it. Some of these projects turned out to be productive and some not, but I always thought they would be definitely more productive than social transfers. But this year, the debt buildup in the US has funded zero new productive investments. No new roads, no airports, railroads, nothing. They were basically just sending money to people to sit at home and watch TV. In the end, this buildup of unproductive debt can be reflected in one of two things: Either in the cost of funding for the government, i.e. in rising interest rates, or in a devaluation of the currency. This is what the French economist Jacques Rueff taught us years ago. Very soon, this is going to put the Fed in a quandary.

In what way?

They will have to decide whether to let bond yields rise or not. If they let them normalize to pre-Covid levels, 10-year Treasury yields would have to rise to about 2.5%. But if they do that, the funding of the government becomes problematic. A 50 basis point increase in interest rates is equivalent to the annual budget for the U.S. Navy. Another 30 bp is the equivalent for the U.S. Marines, and so on. The U.S. is already borrowing money to pay its interest today. If rates go up, they’re getting into the cycle where they have to borrow more just to be able to pay interest, which is not a good position.

Do you expect the Fed to move in and cap interest rates?

Yes, I do. And when they do, I’d say the Dollar will take a 20% hit.

Ten year Treasuries currently yield around 0.95%. At what level will the Fed step in?

I think they will have to cap interest rates at 2%, otherwise the drag on the government will become too big. That question will arise rather soon, because come this spring, the base effects for growth and for inflation will kick in. Growth will be very strong, and so will inflation, which means that yields will quickly try to get back up to 2%.

«Capital flows into positive real rates just like water flows downhill.»

You recently wrote a piece where you recommended buying gold and financials to prepare for this event. Why gold, and why financials?

My base case is that Treasury yields will move up to around 2%, at which point the Fed will introduce some variant of yield curve control. In this case, the Dollar would tank, real interest rates would drop and gold would thrive. But maybe I’m wrong, maybe the Fed freaks out when they see inflation rising to 4%, and maybe they decide to let yields rise. If that’s the case, then financials will rip higher, driven by a steeper yield curve. So come this spring, if the Fed caps interest rates, gold will thrive, and if it doesn’t, financials will thrive.

But you’d lean towards gold?

Yes. It’s quite possible that in the coming weeks, the Dollar will rise while Treasury yields move up. This could provoke a sell-off in gold. If that were to happen, I’d take the other side of that trade, I would buy gold. But at the same time, you can buy out of the money call options on financials. That would be the hedge for the scenario of the Fed changing its mind and letting the yield curve steepen.

The Dollar has been strong for the past ten years. Has it entered a new structural bear market?

Yes, there is no doubt in my mind. A year ago, the Dollar was the only major currency offering positive real rates. My view is that capital flows into positive real rates, just like water flows downhill. Today, the U.S. has one of the most negative real interest rates worldwide. Given the year-on-year rise we will see in inflation this spring, real interest rates in the U.S. will drop even further.

Apart from negative real yields, what are the other reasons for the Dollar bear market?

We first have to ask ourselves why we even had a Dollar bull market in the past decade. The answer is the shale oil revolution. As the United States moved towards energy independence after 2011, its trade deficit shrank. The shale oil revolution meant that all of a sudden, the U.S. was no longer exporting money.

And that tide has now turned?

Yes. Oil production in the U.S. is collapsing. The Texan wildcatters have lost out in the price war against the Saudis and the Russians. U.S. oil production has already gone down 2.5 million barrels per day and is slated to go down by another 2.5 million over the next twelve months, because every major oil company is cutting capital expenditures. Just look at Chevron and Exxon, their capital spending plans over the next five years are at half the level they were in 2014. And so, as the U.S. economy picks up after Covid, America will be importing oil on a massive scale again. The U.S. will be back to exporting $100 to $120 billion to the rest of the world, mostly to places that don’t like America, who will turn around and sell those Dollars for Euros. This is bearish for the Dollar.

When we see the oil price heading above $50 again, wouldn’t that cause US production to rise?

You can’t turn up oil production like a tap. It will take at least a couple of years to come back. Plus, shale oil production in the U.S. was hugely capital destructive. More than $350 billion was lost in the shale oil patch over the past ten years. Look at the energy sector today, it’s at 2.5% of the S&P 500. When oil was at $10 per barrel, back in 1999, energy was 5.5% of the S&P 500. So I’m going to answer your question with another question: If oil prices go up, and the U.S. could produce more oil again, it would require hundreds of billions of Dollars in capex. Who will provide that kind of capital, with an incoming Democratic Administration that has been ambivalent about fracking? I don’t see it.

So we are moving back into a world where the U.S. is a structural oil importer and a Dollar exporter?

Yes. The seeds are planted. That’s a huge shift that I don’t think people are taking into account yet.

When the world economy normalizes after the pandemic, where will the oil price settle?

Before Covid, it seemed that the oil market had found a balance between 60 and 80 $ per barrel.

Is that the range we’ll head back to?

I think so, and for a pretty simple reason: Above 80 $, China basically stops buying. That’s a big difference relative to ten to fifteen years ago, when China hadn’t built any sizeable inventory and was a forced buyer of oil. This is no longer the case. In fact, you saw it during the Covid crisis: Between April and June, when the oil price collapsed, China imported about 13 million barrels per day, which was 40% more than normal. Clearly, they were building up inventory, taking advantage of the low price. China is the marginal buyer, and its behaviour is a key driver for the oil price: Above 80 $ they stop buying, and below 60 $ they buy in size. Incidentally, in that range, many oil companies make pretty decent money. Saudi Aramco makes a killing at this price level.

You see the Dollar in a bear market. Meanwhile, the Renminbi has strengthened significantly. Is that also a structural shift?

I think so. In the past, every time there was a crisis, the reaction of the People’s Bank of China was to freeze the exchange rate. During and after the global financial crisis, the RMB flatlined against the Dollar at 6.82 for two years. In 2015, when the Chinese equity bubble burst, the RMB was flat for several months. When things went bad, historically, they froze it. Not this year. This year, we saw the sharpest six month RMB rally in history. That is a clear change in policy.

What’s behind that change?

I don’t know, but the facts are clear. China today is the only major economy in the world that offers large positive real interest rates. Thus, capital flows into the Chinese bond market. The PBoC is the only major central bank publicly saying they won’t destroy their currency and they won’t proceed to the euthanasia of the rentier. The consequences of this are hugely important. A strong RMB is a fundamentally inflationary force for the world economy.

How so?

Manufacturers around the world have to compete with Chinese producers. Therefore, a weak RMB drives prices down, whereas a strong RMB drives prices up. You can compare it to the role of the Yen forty years ago. A stronger RMB means stronger consumption in China and Asia, and it means that whatever we buy from China is going up in price. It’s not surprising that as the RMB rerates, the U.S. yield curve steepens and oil prices go up: It’s all part of the same reflationary backdrop.

Given this backdrop: Do you see a return of structural inflation in Western economies?

Yes, I think inflation will come back with a vengeance. One of the key deflationary forces in the past three decades was China. I wrote a book about that in 2005; I was a deflationist then, as my belief was that every company in the world would focus on what they can do best and outsource everything else to China at lower costs. But now, we’re in a new world, a world that I outlined in my last book, Clash of Empires, where supply chains are broken up along the lines of separate empires. Let me give you a simple example: Over the past two years, the US has done everything it could to kill Huawei. It’s done so by cutting off the semiconductor supply chain to Huawei. The consequence is that every Chinese company today is worried about being the next Huawei, not just in the tech space, but in every industry. Until recently, price and quality was the most important consideration in any corporate supply chain. Now we have moved to a world where safety of delivery matters most, even if the cost is higher. This is a dramatic paradigm shift.

And this paradigm shift will be a key driver for inflation?

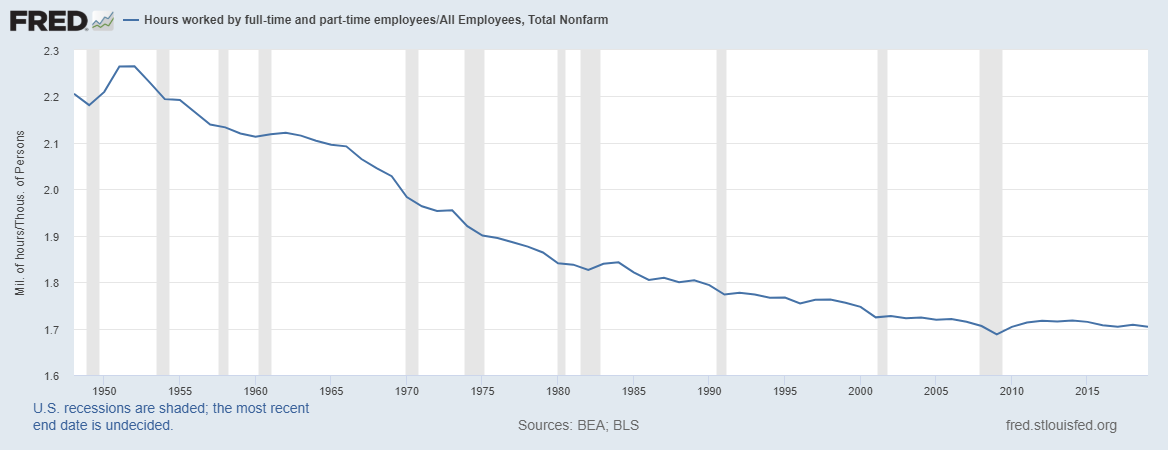

Yes. It adds up to a huge hit to productivity. Productivity is under attack from everywhere, from regulation, from ESG-investors, and now it’s also under attack from security considerations. This would only not be inflationary if on the other side central banks were acting with restraint. But of course we know that central banks are printing money like never before.

«I’m a big bull on Japan.»

What will that mean for investors?

First, there will be two kinds of countries going forward: countries that massively monetized the Covid shock and those that did not. I’d compare the picture to the late 1970s, where countries like the U.S., the U.K. or France monetized the oil price shock, while Japan, Germany and Switzerland did not. This led to a huge revaluation of the Yen, the Deutschmark and the Swiss Franc. Today, the Fed and the ECB were among the central banks that massively monetized, while many central banks in Asia did not. So I expect a big revaluation of Asian currencies over the coming five years, which in itself is inflationary for the world. If you look at the U.S. today, inventories are at record lows. With the economy improving in 2021, companies will have to restock, and they will have to restock with a falling Dollar. The Dollar is down 20% to the Mexican Peso over the past six months, down 10% to the Korean Won, down 8% to the RMB, so whatever Americans buy from abroad will be more expensive. Countries with weak currencies, the U.S. first among them, will have higher inflation.

Where will inflation rates settle?

I don’t know. There is the idea among central bankers that they can engineer inflation rates around 2.5% and keep them there. I doubt that this will be possible to control. But just for the sake of it, let’s assume they manage to do what they say, that they are the perfect engineers they think they are and get inflation at 2.5% for the next five years. Why on Earth would you want to own Treasuries at 0.9% or German Bunds at below zero? You don’t even have to get to a scenario where inflation accelerates to 4 or 5% to see that bonds are madness today. Even if central banks just manage to do what they say, you are guaranteed to lose money with bonds.

What should investors do to position themselves in this new world?

In the old world, where interest rates were falling, the Dollar was strong and oil was weak, you bought Treasuries and U.S. growth stocks and went to the beach. Now, the world has changed. This means you have to stay away from bonds and U.S. growth stocks. In a world of Dollar weakness, you buy emerging market equities and debt, and within emerging markets, I prefer Asia. In a world where either the yield curve will steepen or the Dollar will collapse, either financials or the commodities sector will be doing well. Everything seems to point towards commodities, including energy, but as mentioned, I’d still buy financials as a hedge against a steepening yield curve. So, in a nutshell: Buy value stocks, buy the commodities sector, and buy emerging markets. And for the antifragile part of your portfolio, buy RMB bonds and gold.

How about Japan?

Absolutely, Japan is in a stealth bull market, it has been very strong, and nobody talks about it. We never get questions on Japan from clients. I’m a big bull on Japan, it’s not a crowded trade, so I feel comfortable in it. In a world that is reflating, Japan typically does well. And in this unfolding new Cold War between the U.S. and China, Japanese industrial companies are well positioned.

Aren’t you a bit early in writing off big U.S. tech?

Growth stocks have had their run in the past ten years, with falling bond yields and a rising Dollar. In a reflationary world, they will underperform. Plus, tech is the main battleground in the war between the U.S. and China. I see the tech world breaking into three separate zones, one dominated by America, one dominated by China and India evolving into a zone by itself. You can own the champions in each zone, which means you can own Amazon or Google for the West, or Tencent in China. In danger are companies that straddle the two worlds. Huawei tried, and we saw it being killed. I see Apple at risk, too. I know I said this to you a year ago, and I turned out to be completely wrong, but I still think Apple is in danger, as it straddles the U.S. and Chinese tech spheres.

We should think of Taiwan the way we used to think of Saudi Arabia.

In the middle of this tech war sits Taiwan. What are your thoughts about Taiwan and the semiconductor industry?

Taiwan today is what Alsace-Lorraine was 120 years ago. There were two hugely important events this year that most people have missed because of the Covid crisis. One, the market value of the global semiconductor industry has moved above the market value of the global energy sector. The market is telling us that semiconductors are more important than energy; they are the commodity of the future. We should think of Taiwan the way we used to think of Saudi Arabia.

What’s the second important event?

At the end of 2019, the market value of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing was $200 billion, while the market value of Intel was $350 billion. Today, TSMC is $450 billion, while Intel has dropped to $200 billion. Why? This summer, TSMC came out and said they can produce 7 nanometer chips and will be able to produce 3nm chips in 2023. A week later, Intel came out and said they won’t be able to produce 7nm chips by 2021. So in the summer of 2020, we witnessed the passing of the technological baton from Intel to TSMC. The leadership in the semiconductor industry now belongs to Taiwan.

Why does this matter?

It matters because Washington has decided to make semiconductors the battleground in its war against China. And that means that Taiwan is the battleground in the great conflict of the 21st Century, an island that Beijing regards as a renegade province, sitting 60 miles from its shore. Taiwan has always been a sore point between China and the U.S., even when Taiwan produced plastic toys and bicycles. Imagine if Saudi Arabia was a political uncertainty between America and China, where the regime depended on Washington for survival, but the territory was claimed by China. We’d be very worried.

How will that conflict play out?

I don’t know what will happen. But I’d just say that the fact that the Trump Administration decided to make semiconductors the battleground in its fight with China strikes me as extremely dangerous, given the fact that the U.S. has just lost the technology leadership baton to Taiwan. That, to me, will be the most important event in 2020, more important than Covid.

https://themarket.ch/interview/louis-gave-inflation-will-come-back-with-a-vengeance-ld.3307

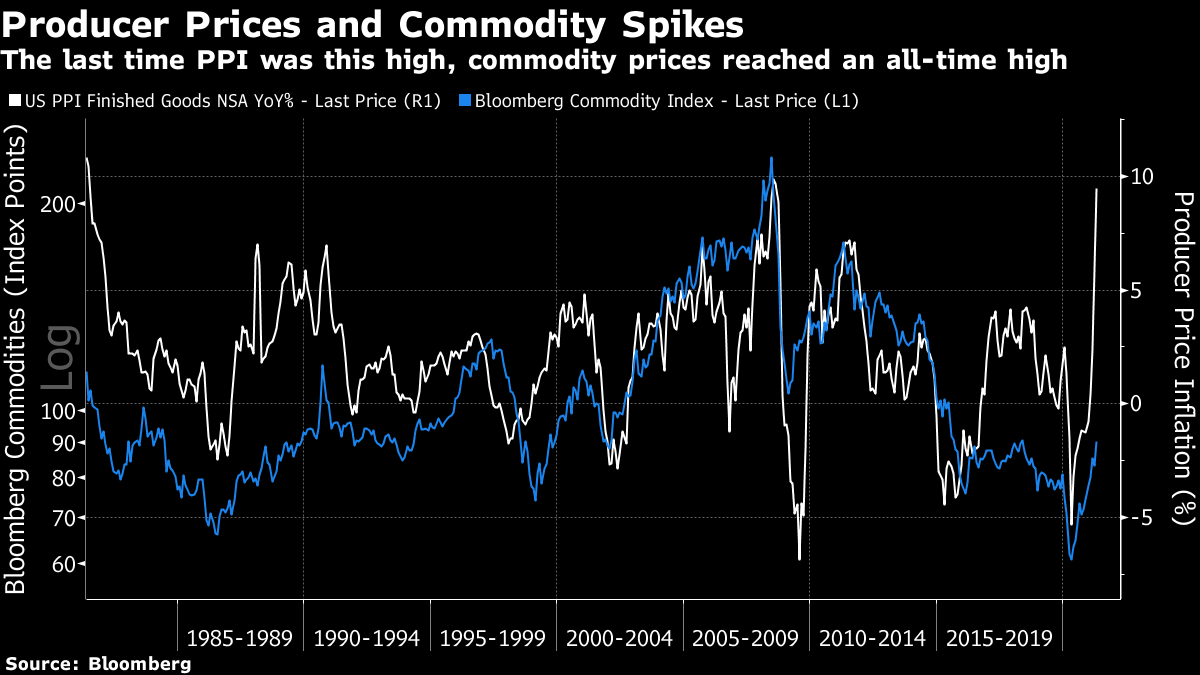

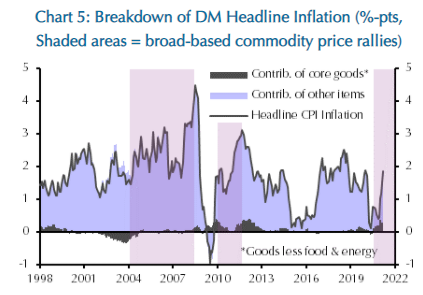

The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher:

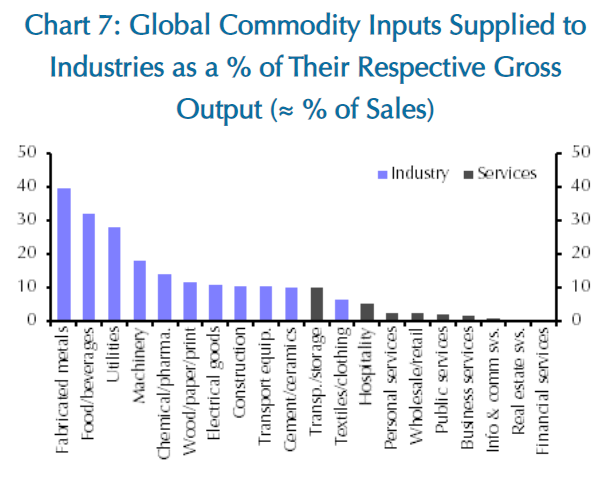

The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher:  The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics:

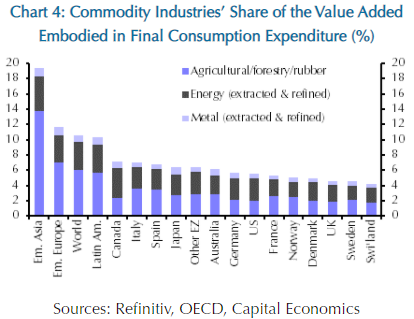

The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics:  But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent:

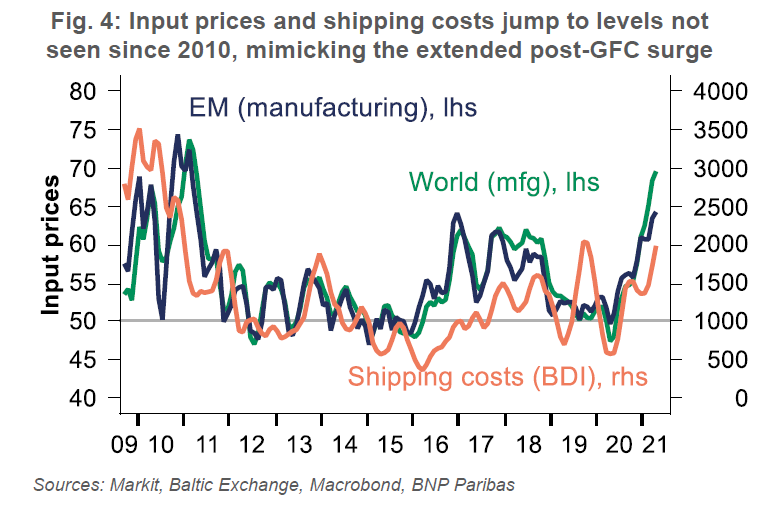

But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent:  One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over:

One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over:  This raises the disquieting prospect of

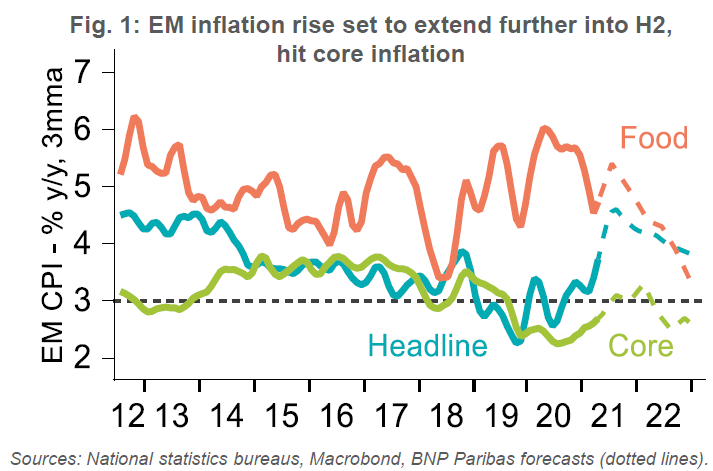

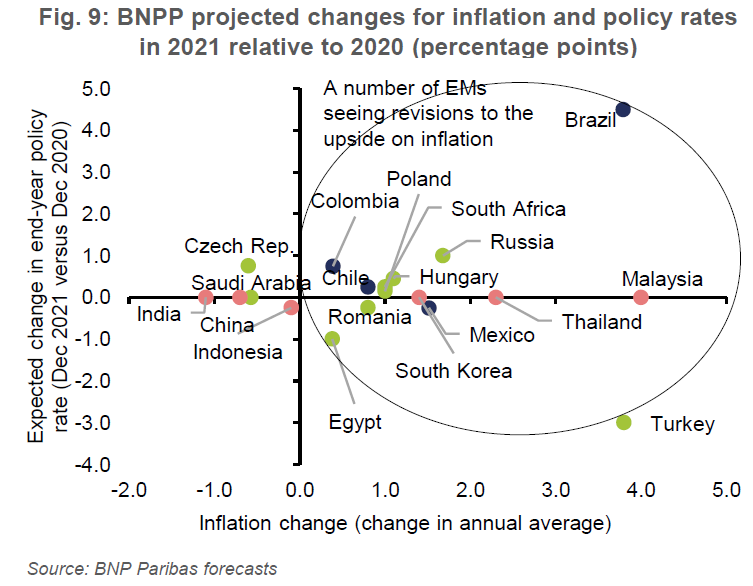

This raises the disquieting prospect of  This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course.

This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course.  Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge.

Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge.