Russell Napier writes….

The solid ground

For many investors the meltdown in emerging market exchange rates is just some temporary contagion from Turkey; it will go away. The reasoning goes that it is a myopic liquidation of perfectly good assets, just because Turkey happens to be classified as an emerging market. Your analyst has long disagreed with that and late last year outlined the consequences for emerging markets from the bankruptcy of Turkey – The New Debt Crisis and What it Means (The Solid Ground 4Q 2017).

Of course the greatest surprise for investors is not that this is a problem for emerging markets but that it is, much more importantly, the beginning of a European crisis (see When Monetary Systems Fail – A Guide For The Cautious 2Q 2018). However, it is not just the negative impacts from the broad financial forces outlined in these reports that are depressing emerging market exchange rates. There is something much more important and insidious undermining these exchange rates: the rise of the rule of man and the decline of the rule of law.

Professional investors have become entirely distracted from the structural decline in the rule of law in emerging markets, as they beat themselves up about Brexit and the Trump Presidency. Given the backgrounds of the average investment manager, it is not surprising that their attention should be diverted to these local issues that challenge not just their portfolio values, but also their personal values. Whatever these two political shifts represent, however, they do not represent a decline in the rule of law. If the US does have a President, whether Republican or Democrat, who breaches the law then it is highly likely that they will be held to account by the legal process.

Similarly, with Brexit the UK’s exit from the EU represents no threat to the rule of law, simply a different and more directly accountable legislature that will enact those laws. Whether you like the impacts that Brexit and Trump are having on your belief system or your way of life they are not a threat to the legal systems that protect your clients’ savings. Sadly, in emerging markets the rise of the strong man and the decline of the rule of law are indeed undermining savers’ legal title to their assets and the cash-flows from those assets.

Investors simply refuse to see it, so intent are they on traducing what they see as the failings of their own political systems. It is time to refocus on what really counts for investors and above all else, above who runs the country and even how they run it, investors must worry first about whether the return of their capital is protected by law. Crucially, even if foreign investors refuse to acknowledge the decline in property rights in key emerging markets, the local investor, being much more fully exposed in his person as well as his property, acts to remove his property. Across key emerging markets we are not just witnessing a contagion from Turkey, but the outflow of local capital that follows when the rule of man rises and the rule of law declines.

Now I fully expect to get a flood of emails from distressed investors questioning such a pessimistic outlook for emerging markets. After all, they don’t have Trump and they don’t have Brexit, so they must be OK. However, they do have Duterte, Erodgan, Xi, Orban, Amlo, Maduro, Putin, Kaczyniksi, and Manangagwa – amongst others. Few if any strong men can ultimately strengthen the rule of law that is ultimately the only protection for investors. In strengthening the law, they weaken themselves.

Investors brought up in the developed world take for granted the stability and continuation of the rule of law. They expect it to be as available and constant as air. Anyway, what role can a consideration of the rule of law play in trying to obtain index beating quarterly returns? It is this myopia and not the myopia associated with the short-term dumping of assets, because they are labelled ‘emerging markets’, that is particularly dangerous. The history of emerging markets is the history of populism, the real populism that subverts human rights and property rights. On the rise in emerging markets, this populism is resulting in a growing exodus of what are now very large sums, even in global terms, of local savings.

It is the shift in local savings, more so than foreign savings, that is pushing emerging market exchange rates to ever lower levels. It is not the flighty financial capital seeking slightly better interest rate differentials that departs in situations like this. It is the financial capital that funds development and growth that flees, as the rise of the rule of man begins to squeeze out the rule of law. The loss of such capital has profound long-term economic impacts.

There is a key reason why the strong men are on the rise and the rule of law on the decline: the world is failing to inflate away its debts. Even before we invented paper money, there was a well recognized method of inflating away debts. Perhaps most famously Henry VIII’s so-called great debasement (1554-1551) inflated away the excessive debts run up to fund wars with France and Scotland, as well as a bit of lavish spending by the king himself. Your analyst meets investors almost every day who believe that inflation is currently playing a similar role. However, such an assertion ignores the fact that the global non-financial debt to GDP ratio is now 244% up from what seemed a dangerous level of 210% of GDP as the global economy peaked in December 2007.

All the evidence suggests that the authorities have so far failed to inflate away their debt burdens and thus some are now turning to more extreme solutions. As The Solid Ground has long pointed out, it is impossible to inflate way debts denominated in somebody else’s currency, and once again many emerging markets find themselves with too much foreign currency debt. It is thus emerging markets that will be forced to take extreme measures first, and extreme measures require extreme leaders.

Default is one solution, particularly if one has the luxury of defaulting on a foreigner, or sequestration of private wealth under various guises is another. Given the need for such extreme measures when countries fail to inflate away their debt, it should be no surprise that the rule of law is on the ebb and the rule of the strong man is creeping in.

Of course, investors have found themselves threatened with sequestration before in times of crisis in emerging markets. However, in recent decades they have always had the foot soldiers of the IMF to intervene on their behalf. For a generation the IMF conditions for large bail-out loans enforced private property rights and enforced economic policies that would ultimately be to the benefit of both local and foreign investors. Now the IMF has changed its mind. In November 2012 it published The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows: An Institutional View. That document concluded on page 6 “capital controls form a legitimate part of the policy toolkit”, and the executive summary of the document places their appropriate use in context:

‘Rapid capital inflow surges or disruptive outflows can create policy challenges. Appropriate policy responses comprise a range of measures and, involve both countries that are recipients of capital flows and those from which flows originate. For countries that have to manage the macroeconomic and financial stability risks associated with inflow surges or disruptive outflows, a key role needs to be played by macroeconomic policies, including monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate management, as well as by sound financial supervision and regulation and strong institutions. In certain circumstances, capital flow management measures can be useful. They should not, however, substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustment.’

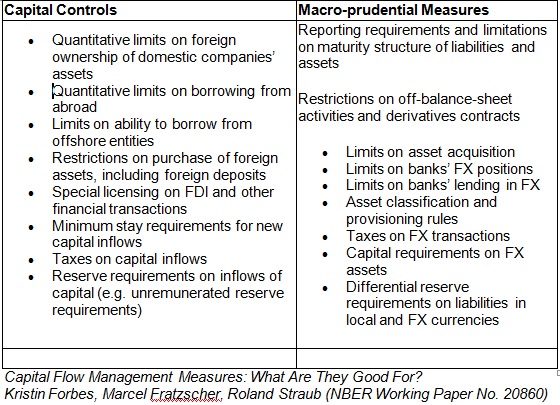

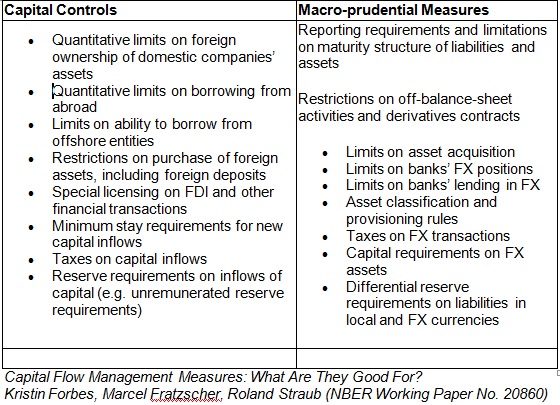

Capital controls do not need to be called capital controls. Your analyst has long argued that so-called macro-prudential regulation tools can be used as tools of financial repression, to keep the yield curve below the rate of inflation. A key part of any successful repression is to control capital flows and force savers to hold assets that offer a high prospect of negative real returns. In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2015, the authors also recognise that ‘capital flow management’ and ‘macro-prudential regulation’ can both be used to achieve restrictions on the free movement of capital. The authors’ list of measures provides a guide as to the measures from each toolkit that can amount to de facto as well as de jure capital controls.

Types of Capital Flow Management Techniques

Investors must not be surprised if an IMF bailout package contains capital controls and the IMF goes from enforcing your rights to stripping you of those rights. Capital controls lock investors into a pot of assets denominated in one currency, and thus leave them at the mercy of the government policies of that particular jurisdiction. Capital controls have been the first step in the process through which wealth is re-assigned, whether through inflation or more directly, from the private sector to relieve the debt burdens of the state. Importantly capital controls destroy liquidity in assets increasingly held in open-ended structures offering daily redemptions in developed world currencies. We cannot know when the IMF will finally endorse the use of capital controls as part of a bailout programme, though it is worth noting that the IMF worked as part of the troika in Greece keeping in place capital controls originally imposed by the Greek government. Similarly, in Cyprus IMF involvement with the country occurred with capital controls in place. According to Panicos Demetriades, former central bank governor of Cyprus, the policy makers that investors rely on to defend their property rights have a very different view on their role –