Market strategist Russell Napier talks about why he sees structurally rising inflation coming, why central banks are impotent – and what that means for investors. Mark Dittli 13.07.2021

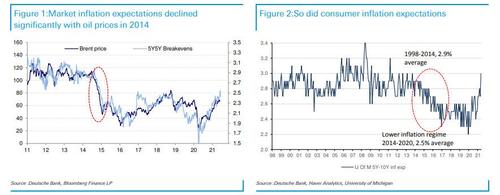

Russell Napier caused a stir in the financial world one year ago when he made the call for a regime change: After almost thirty years in which the global economy was characterized by deflation, the market observer thinks that a phase of structurally rising inflation is beginning.

Just like after World War II, Napier believes that governments will pursue a policy of financial repression in which the interest rate level is deliberately kept below the rate of inflation to get rid of the high levels of debt.

The Market NZZ spoke with Napier about his inflation call. In this in-depth conversation, which has been redacted for clarity, he explains which developments will shape the coming years, how investors can prepare for them – plus why trying to forecast the velocity of money is akin to juggling an incontinent squid.

Mr. Napier, it’s been a year since your inflation call. Today, we do see higher headline inflation. Do you take that as proof that you were right?

Yes, but we need to distinguish here. My call is based on money, on the growth rate of broad money, to be precise. My argument rests on the observation of a deep, structural shift taking place. What we see today in terms of published inflation is partially based on supply shortages. These will ultimately be solved.

Most of the discussion circles around the question whether current inflation is transitory or persistent. What tells you that it will be persistent?

First of all, I agree that a lot of the inflation we see today is caused by the supply side, which will adjust. That element of inflation will come down again, hence we can say it’s transitory. I would put one red flag over the supply side issue though, and that is China. Remember, in 1994 China devalued its currency, as I show in my upcoming book «The Asian Financial Crisis 1995-1998», and this triggered a wave of cheap exports from China. For years, we had a massive deflationary wind coming out of China. That isn’t going to happen again for two reasons: One, labour prices in China are up significantly. And two, we are entering a new cold war, which means we won’t be buying as much from China. But let’s leave this issue aside and assume that the supply side will adjust. In the longer term, inflation will be driven by the growth of money in circulation.

How so?

My bottom line is we have an exceptionally high growth in broad money at the moment. The US got to 27% year-on-year growth in M2 at one point. That’s coming down now, given the base effect, but I think M2 growth in the US will settle at around 10%. In Europe, it is about 10%, and even in Japan it’s well above its post bubble-era average. So I think we will settle down with broad money growth at close to 10%, persistent, over several years. The consequence of this kind of broad money growth is an inflation rate above 4%.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/gKfCV/1/

Why?

First, it’s important to stress that I’m not calling for 10 or 20% of inflation. There are people running around with hyperinflation forecasts, but I think this is unlikely. I’m calling for an inflation rate above 4% for a number of years, and that is based on an analysis of the quantity of money. Have we ever seen a country in history persistently running a broad money growth rate at 10% that didn’t have inflation at 4% or above? The answer is No. Plus, it is fair to assume that there will be spikes in the velocity of money, which means there can be temporary bursts taking inflation above 4%.

What time frame are we looking at?

Over the next ten years, I’d forecast something between 4 and 5,5% in terms of the rate of inflation in the developed world. But mind you: The most important part of my forecast is not the inflation rate per se. It’s that interest rates will not be allowed to reflect that rate of inflation. That is what changes the entire structure of finance. This is the key question: Will interest rates, short and long, be allowed to reflect 4% inflation? My answer is No. This is because we will be entering a period of financial repression, where governments keep interest rates below the rate of inflation, just like after World War II.

What’s the base for your forecast of a broad money growth rate of 10%?

The reason that I come up with this number is the revolution that happened last year: Governments got involved in the commercial banking system, by guaranteeing private sector loans. When I look at the latest data, I see bank balance sheets growing at about 10%, which translates into broad money growth of around 10% per annum. People have to understand that it’s not central banks that create most of the money, but commercial banks. So now governments, through their loan guarantees to commercial banks, can create as much money as they like. Out of thin air.

Sure, but those were emergency measures to combat the effects of the pandemic.

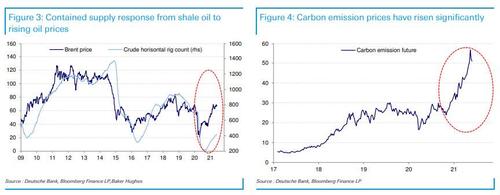

Many people will say it was an emergency measure, and when the pandemic is over, governments will stop it and bank credit growth will collapse. Well, we shall see. Governments have huge political goals, like reducing inequality, boosting green investment, infrastructure, you name it. I think we will see more government guarantees, particularly for green lending. As it happens, there is also, for the first time in my career, likely to be a series of private investment booms by corporations, be it for green investments or investments into new supply chains. So the forecast of 10% broad money growth is based on a rapid expansion of bank balance sheets, which is either driven by private sector demand, and if that fails then driven by the government getting in to manage the expansion in bank credit they require to meet their political goals.

And central banks will have no say in the management of broad money growth?

No, they won’t. This is exactly what happened after World War II. Central banks were impotent during that time. The supply of money was dictated by governments controlling the commercial banking system. I strongly believe that we’re going back to that system. The government can never tell you that, because the whole point of financial repression is to steal money from savers slowly. But this is a fantastic thing for politicians: It isn’t fiscal spending, it isn’t higher taxation, it’s a contingent liability on the government’s balance sheet but not an actual liability. It creates politically directed growth, and it creates inflation. For politicians, it’s the magic money tree.

And your case is that politicians won’t let it go again?

Exactly. Let me give you an example: In the UK, usually the longest term fixed mortgage you could normally get was five years. Boris Johnson has now created a 25 year fixed mortgage for first-time buyers, offered by banks, guaranteed by the government. Nobody can pretend that this has anything to do with Covid, and in fact when Johnson announced it, his stated aim was to give young people access onto the housing ladder. This is a good example of how the magic money tree was discovered for Purpose A, i.e. Covid, and is being used for Purpose B, furthering social justice.

Don’t you see a possibility that politicians will return to being fiscally responsible?

Of course it’s possible that politicians, having discovered the easy route to re-election, decide not to use it. I’m betting against it. The introduction of the income tax in the UK was an emergency measure in 1798. It’s still in effect today. Many emergency measures, such as Regulation Q introduced by the US government to control deposit rates in the 1930s, lasted for decades.

Seeing how Republicans in Congress are trying to block Joe Biden’s infrastructure plans: Perhaps there will be a push towards austerity again?

The Republicans were in charge during most of Covid. They came up with the Payment Protection Programme, which was exactly using the banking system for this purpose. History shows that when Republicans are in power, they have endorsed fiscal largesse, price controls, credit controls. Just think of Richard Nixon. Of course it’s possible that some sort of rectitude descends on politicians. But I think it’s unlikely. Politicians will push credit for green investments. There will no doubt be other political problems for which more cheap bank credit is seen as the answer.

The bond market today clearly does not reflect your inflation call. Why?

Bond yields are depressed by central bank action, and I would argue that they are also depressed by government action. Many insurance companies must hold government bonds due to asset liability models that their regulators have imposed upon them. We are going to discover that, as time progresses, bond yields are entirely decoupled from inflation. That’s the most important thing here. You won’t find one economic textbook which says that bond yields can be decoupled from inflation. And yet there is a long period of history, from 1939 to 1979, where they were largely decoupled. All the textbooks work on the assumption of a free market economy where the free will of investors results in bond markets pricing in inflation expectations.

Is that not the case anymore?

Bond yields are telling us today that this is history. They are not set in a free market anymore. And therefore most of the skills investors have learned since 1979 are obsolete. Bond yields will not be a free market price anymore for at least 15 years. We are in a new structure of how things work. I am not making a business cycle call here, this is a structural call. We are entering a time of financial repression.

Why are yields not just signalling that they are not convinced that inflation is going to stick?

As you know, I was on the deflation side of the argument for 25 years. The reason I changed is because the structure has changed. Banks didn’t lend up until 2019, broad money was stagnant, velocity fell, so you had to be on the deflation side. But now banks do lend, because they are compelled to by the government, broad money is growing, and, as we will find out, the velocity of money will be rising. That’s why I’m in the inflation camp now.

In the US, velocity of money is stuck at rock bottom. What does that tell you?

It tells me that many things are still difficult to buy: Part of the service sector is still effectively closed down until people feel confident about the health issue. In other parts of the economy, velocity is shooting up. The building trade is the obvious one, where people take their cash balances and buy building materials they don’t actually need yet. That’s the classic example of rising velocity.

Velocity has been on a structural downward shift since 2009. Why?

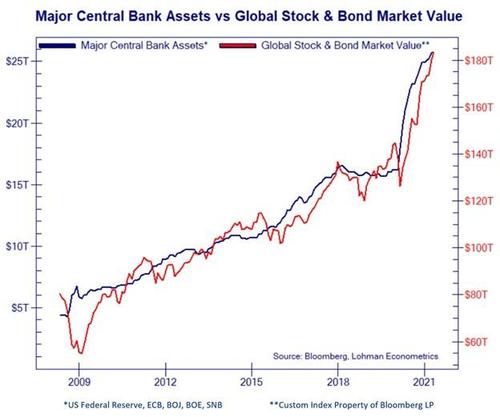

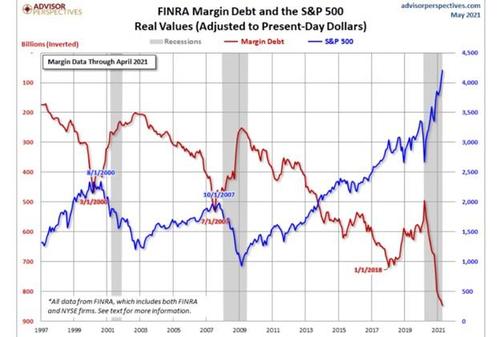

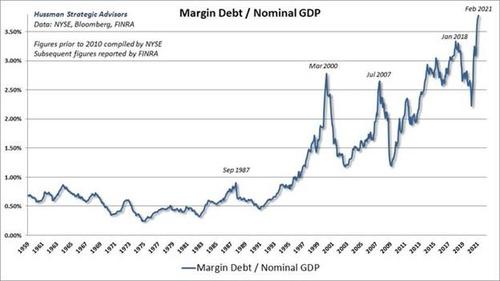

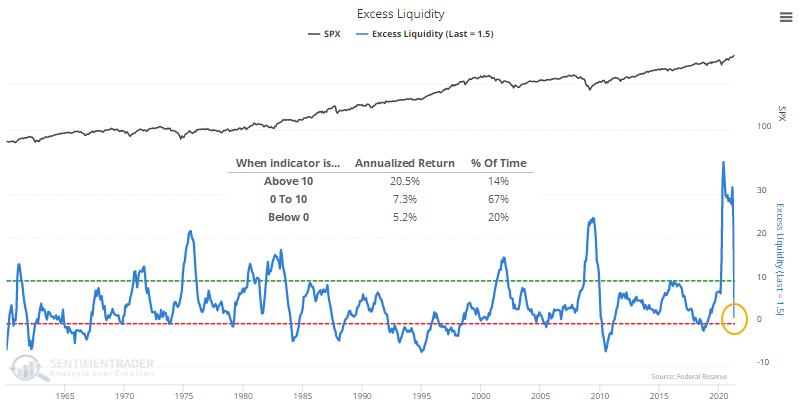

If you look at US financial history, velocity was in a rather stable range above 1.6 from 1959 to 2009. The downward shift after 2009 was, in my view, the result of the Fed’s quantitative easing policy. With QE, the Fed bought financial assets in the market, and it basically bought them from savings institutions. The only thing these institutions could do with the newly created liquidity was to buy more savings assets. So the QE policy never reached the real economy, it never created broad money growth, it just pushed up asset prices. But now, with broad money created by the banking system, it will hit the real economy, therefore velocity will normalize.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/Ho3JA/1/

To what level?

I think the great surprise over the coming years will be when velocity goes back up towards 1.6. But forecasting velocity is fiendishly difficult. It’s like trying to juggle an incontinent squid: Something you really don’t want to do, and you’re very unlikely to be successful. The change in velocity downward after 2009 fooled everybody. Many people at the time said that QE must create inflation. But because velocity collapsed, there was no inflation. I think it will surprise on the upside this time. So while we can’t forecast velocity, we can put a risk to it, and I think the risk of velocity shooting up is higher than any time since the 1970s.

What will cause velocity to take off?

When people decide their savings can’t be sustained and do something with it. This will happen when the government starts to cap bond yields at a level permanently below inflation.

Won’t this just provoke another leg up in real assets, like equities?

Yes. That’s why I’m bullish on equities and real estate. As the experience during the three decades after World War II has shown, in the early stages of financial repression, equities and real estate are beneficiaries.

What do you make of the hawkish pivot of the Fed, and their beginning of the taper talk?

I think central banks are irrelevant, because they don’t control the growth of money anymore. Of course, when you have a regime change, people will keep looking at the old regime. Investors still take their leads from central bankers. But look at the British Covid bounce-back loans: The government has dictated the quantity, the interest rate, the duration, and the credit risk. What role does the Bank of England have to stop that? None. All the tools central banks have are fairly meaningless should governments continue to dictate the extension of bank credit on the terms they deem necessary. The power is gone from central banks. The most important call I’m making is that the institutions investors thought were important are in fact irrelevant.

So you say it’s the governments that will put a cap on bond yields, not central banks through a policy of yield curve control?

Yes, and that’s important. It comes in two stages. In the first stage, the one we are living through now, bond yields are largely driven by the central banks. But there will come a time when they don’t want to continue QE as it is a pledge to add unlimited liquidity which is dangerous when market participants believe in higher inflation. Many people think yields will shoot up once central banks stop buying bonds.

Won’t they?

No, because then the government will force savings institutions to buy bonds. That’s stage two of bond yield control. Mind you, the transition from stage one to stage two won’t be smooth. Legislation will have to be passed to allow governments to in effect allocate private sector savings through greater control over regulated financial institutions. So there could be a period where bond yields rise too quickly and markets will panic. But ultimately governments will cap interest rates by using the savings system. Just like they did after World War II. In basically all our economies, our total government and private sector debt to GDP is above 1945 levels. Why should we not expect governments to use the same mechanisms they used after the war to get those debt levels down? It is a transfer of wealth from savers, forced to own fixed interest securities on low yields, to debtors who see their revenue rise with inflation while their interest payments remain low.

In order to be able to do that, any idea of central bank independence would have to be scrapped?

Yes. It’s like the Holy Roman Empire: It existed for a thousand years, but it wasn’t powerful. It was there, people talked about it, but it was powerless and meaningless. We can say central banks are independent, but all the power is with the government. Andy Haldane, the outgoing chief economist of the Bank of England, wrote in his retirement epistle that for years after World War II, the Bank was effectively a think tank, and the government set interest rates. We can go back to that. You will never formally relinquish independence, but your power slips away. There is no independence in central banking anymore, it’s gone, it’s passed, it has ceased to be. This has happened before, and it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Haldane also wrote that he thought the most important task of central banks today was avoiding an upside inflation surprise.

If I were leaving, and if I wanted to be seen favourably by history, I would also tell the institution that they should do something. But they can’t. It’s not up to them. They don’t control the creation of money anymore.

But in the short term, central banks could provoke a tapering scare anyway?

Winston Churchill used to say it’s better to jaw-jaw than war-war: If you don’t have any power anymore, then talk like you do and sometimes it works for a while. That’s what they will do, and this talking in the short run can be effective. Teddy Roosevelt said «talk softly and carry a big stick». At some point people realize that the central banks don’t carry a big stick anymore. It’s like in the last chapter of the Wizard of Oz, when they discover that the mighty wizard is just a tiny little man behind a curtain playing an organ. They pretend that they are still carrying a big stick. It can work until it doesn’t.

So let’s take the playbook after the war: For about twenty years, we saw high nominal growth, followed by a long period of stagflation. What are we looking at today?

For the average guy in the street, financial repression can look quite good. Let’s say your wage is going up at 5%, and your mortgage rate is 3%. This is not a bad world to be in at all, arguably for the majority of the population even if their wages only grow in line with inflation. The person who pays the price for this is the saver. Even if you just took the period from 1945 to 1957, which was the period where everybody was doing quite well, you lost 35% of your savings if you held British sovereign bonds.

It was a fantastic time for equities, though.

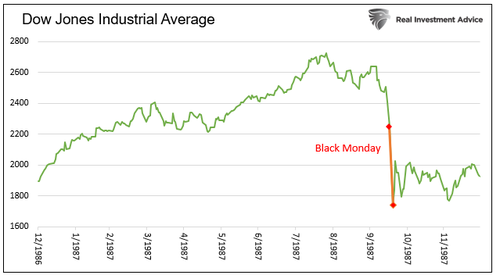

Absolutely, if you had been in equities during that time, you did very well. That’s why I’m bullish for equities today. However, there is one crucial difference: At the end of the war, the yield on ten year Treasuries was 2,5%, and the dividend yield for equities was 10%. Equities started the period of financial repression at dirt cheap valuations. From 1945 to 1966, you had this catch-up where the cyclically-adjusted P/E went from 9x to 25x. Today, equities enter this period at an already very rich valuation.

And then came the era of stagflation.

Starting in the late Sixties, we entered stagflation. There were many factors, and the oil crises were certainly important. But basically the problem is, in the long run, if you put the wrong cost of capital into the economy, you get a misallocation of capital. The word stagflation wasn’t invented until 1966, because we had never seen it before. It was invented by Iain Macleod, who was then the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Over a prolonged period of time after 1945 capital was misallocated, and this resulted in productive capacity not being added in the right places and people not being employed.

Do you expect a repeat of this pattern, first a boom, and then stagflation?

Yes, but I wouldn’t expect the boom phase to last that long. So even though I’m bullish for equities at the moment, the difference this time is they start at an overvaluation, rather than at an undervaluation. A repeat of the long boom from 1945 to 1966 for equities is unlikely.

How long can the good times last?

The first stage can go on for three or four years. That’s short compared to after World War II, but it’s long for many people. The time to sell equities is when governments formally force savings institutions to buy more bonds. Because in order to buy, they will have to sell equities.

And after that, there will be stagflation?

If we agree that stagflation is a consequence of a long period of misallocated capital driven by financial repression, then we have to expect it to happen again. You misallocate capital, and you get high inflation and high unemployment.

One argument that is often heard why a Seventies style stagflation won’t be possible is that unionization of labor is gone.

People always say unionization caused inflation. The statistical evidence suggests that it was the other way around, that inflation caused unionization. People banded together and joined unions to protect themselves from inflation. When there is no inflation, you don’t need to be in a union. I think we will see more unionization again.

Given your bullishness on equities, shouldn’t you also be bullish on gold?

I’m very bullish on gold. The problem for gold in the last year was that interest rates have gone up, because people still believe there will be a link between inflation and interest rates. If people believe there will be inflation at 4%, they will say interest rates will ultimately be at 5 or 6%, hence they don’t want to own gold. It’s only when they begin to realize that that link is broken, that the gold price will lift off.

You have a new book out, «The Asian Financial Crisis 1995-1998». What can we learn from that period today?

I thought it was a good time to write about why we ended up in this kind of situation, where our debt to GDP ratio is above the levels after World War Two. The Asian crisis launched this. After the crisis, Asian authorities introduced policies of exchange rate management, they bought up a huge pile of foreign reserves and Treasuries. By holding their exchange rates down, they pushed a lot of cheap products into the developed world, which pushed down inflation and forced central banks to hold down interest rates. This led to this depression in interest rates and this massive rise in debt. The other thing that happened during the Asian Crisis was the Fed bailed out LTCM, and they cut interest rates to support the bailout. So a lot of people considered this a sign that you can speculate with debt. The foundations for where we are today were laid in 1998. The book explains where our current predicament came from and how the financial repression we now live with is a fusion of the two forms of capitalism, social capitalism and financial capitalism, that did battle in Asia in 1997 and 1998.

Russell Napier

Russell Napier is author of the Solid Ground Investment Report und co-founder of the investment research portal ERIC. He has written macroeconomic strategy papers for institutional investors since 1995. Russell is founder and director of the Practical History of Financial Markets course at Edinburgh Business School and initiator of the Library of Mistakes, a library of financial markets history in Edinburgh. Russell is a CFA Society Fellow.

https://themarket.ch/interview/russell-napier-we-are-entering-a-time-of-financial-repression-ld.4628