Russell Napier writing for The solid ground gives his final warning to get out or get slaughtered

He writes in this must read post……

Regular readers will know that this macro analyst is not particularly interested in the business cycle. This is a form of heresy for those of us who have spent our careers studying and analysing the impact of macro factors on asset prices. Sometimes, however, heresy is what is necessary, though of course it is never welcomed. It becomes a necessity when we face a profound structural change to the nature of the global monetary system. Just such a change is now upon us.

Your analyst is asked regularly, ‘Where are we in the cycle?’ and in recent days many seasoned investors have offered an opinion that we are late cycle. The sport of determining which stage of the cycle we are in is, of course, normally the key to macro investing, but today it is not relevant. Its irrelevance is because we are clearly living through the breakdown in the global monetary order – a profound structural change. I once mentioned this breakdown to the wonderful Jim Grant who replied, in his usual laconic tone, “There’s a global monetary order?”

Well, there is such an order even if, unlike Bretton Woods or the Gold Standard, it does not have a name. It is the order in which China and then, after the Asian Economic Crisis, other emerging markets were allowed to link their exchange rates in varying degrees to the USD. The result was the fastest growth in world foreign exchange reserves ever recorded and thus record purchases of US Treasury securities matched by the creation of money, commercial bank reserves, in the emerging markets.

What nirvana for equity investors when we enshrine a lower global risk-free rate and a higher global growth rate in the seeming structural setting of a monetary order! The agents of debt take full advantage of such opportunities and have thus geared the hell out of assets to increase their own cut on the asset price inflation. To paraphrase William Wordsworth, ‘Bliss in that dawn it was to be alive/But to be geared was very heaven.’ Now the sun is setting.

There is now no growth in world reserves and the US Federal Reserve is actively destroying USD bank reserves. not many can grasp the importance of this)The decline in emerging market share prices from January this year is just the beginning of the adjustment that will now follow. The decline in commodity prices since October now confirms that adjustment, pointing the way to a deflationary, not an inflationary, adjustment.

To worry about what stage we are at in the business cycle today is akin to worrying about the stage of the cycle we were at in 1968 and ignoring the probability that the Bretton-Woods agreement was about to collapse. As the excerpt from the 1968 Wall Street Journal above shows, there was considerable faith that investing in equities for the long term would pay off, particularly as a protection against inflation. Such faith was misplaced. When Rotnem was writing the DJI was just above 900 and as late as 1982 it was just below 800. The general price level, as measured by the CPI, rose by 174% over the same period.

Even for those who worked out that there would be a collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement and also that this would unleash very high levels of inflation equities did not offer wealth protection. When a major structural change comes along other factors such as technological breakthroughs, institutional demands for shares, and supposed inflationary protection, all cited as positives by Rotnem in 1968, are just not that important. That collapse of Bretton Woods sparked an inflationary wave that produced massive negative real returns for investors in both equities and bonds. Those investors who were focused on whether we were in the mid or late cycle in 1968 missed the major post-war structural turning point that brought massive losses to anyone not prepared to adjust for a new monetary system, replete with inflation, by buying commodities, gold and Swiss government debt.

Subscribers will be aware of the arguments behind the call for a breakdown in the global monetary system, and the consequences for asset prices both short-term and long-term. The Newsletter has made it clear that the initial adjustment following such a collapse is probably deflationary rather than inflationary. This, of course, has not been a popular opinion, as not long ago the consensus foresaw synchronised global growth and now we can all witness that the US economy has been buzzing along with a tight labour market. Isn’t the lesson from history that a breakdown in the global monetary order will unleash inflation? Indeed it is, but this need not be the first impact of such a breakdown. There is much evidence of an initial deflationary adjustment, as subscribers will know, but for now let us focus on perhaps the most surprising item of news – there is not enough money in the world!

In the summer of 1987 the well-known monetary guru of Greenwell’s, Gordon Pepper, forecast that there would be a crash in the stock market. He based this forecast on a dramatic slowdown in the growth of inflation-adjusted broad money growth in the UK ( how many track this measure) How, he pondered, could such a slowdown in real broad money be reconciled with the consensus view for solid economic growth, inflation, and a rising stock market? Across the Atlantic Ocean Milton Friedman was staring at similar data for the USA. The Friday before the stock market crash of October 1987 he spoke in New York to warn of a forthcoming recession based upon the slowdown in real broad money growth.

As it turned out we got the stock market crash, but not the recession. The stock market was the key factor that had to adjust and perhaps the economy would have followed if Alan Greenspan, the artist formerly known as ‘The Maestro’, had not slashed interest rates and birthed his now infamous ‘Greenspan put’. So, money may not always matter, but sometimes it behaves in such an extreme way that it matters very much. The collapse in real broad money growth across the world is thus something well worth paying attention to, precisely because nobody is paying attention to it.

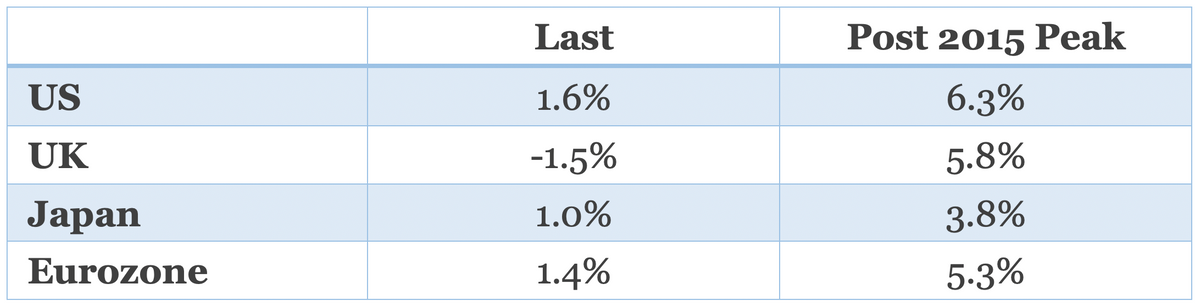

The table below looks at what has happened to real broad money growth in the developed world from recent peaks.

The Solid Ground has long pointed out the failure of the monetary authorities to create sufficient broad money to justify belief in a combination of higher assets prices, continued growth in the real economy and rising inflation. Outside of the US this call has played out very well. The MSCI World ex USA Capital Index is now back at its 2011 level, and bank investors have been particularly heavily punished by the failure of the monetary transmission mechanism over the period.

Of course, in the USA this lack of broad money growth has not prevented a surge in asset prices, a rise in inflation, and reasonable economic growth. Why this is so is probably a large enough topic for a quarterly Solid Ground, but in essence it is because corporate cash-flow has surged during this period, particularly following the Trump tax cuts. Massive share buy-backs in the US have very much kept the equity bull market on track.

However, the table above shows that even in the US we are not living in a world of monetary stasis. As The Solid Ground pointed out in 1Q 2018 (Crowding Out: Higher US Real Rates and Lower Inflation), the added new challenge for the US is that broad money growth remains low while the supply of treasury securities, from the Treasury and the Federal Reserve, at circa US$1.4trillion is rather formidable! If it’s morning in America, who will buy this wonderful morning? In the forthcoming 4Q report The Solid Ground assesses the extent to which that funding burden will fall upon the US or non-US savers. Much depends upon how that funding burden is shared and the greater the burden taken by the non-US saver, the more the divergence of returns between US and non-US equities.( exactly, they will suck worlds saving)

Now we need worry about the fact that real broad money growth has declined dramatically since 2015 and the risks of a deflationary adjustment, through lower real GDP or lower asset prices that undermine cash flows and collateral values, can augur another debt deflation. This slowdown in money is particularly important as the BIS report shows the world’s non-financial debt to GDP ratio has reached yet another all-time high of 246%. So this analyst will not advise investors to play the mid cycle or the late cycle. He advises investors to prepare for the breakdown in the global monetary system and a deflation. Those still sceptical can watch commodity prices as a guide to whether such an outcome is increasingly likely. Those who are prepared to accept that money makes the world go round might contemplate the rapid slowdown in the pace of money supply growth and conclude that something is already stopping.

So as we approach Christmas, the time of carols, why not join the chorus from the musical Oliver!, filmed in 1968 by Carol Reed, and ask how we reconcile ever expanding goods prices, ever expanding asset prices and ever expanding economic activity with the fact that there is too little money.

‘There’ll never be a day so sunny

It could not happen twice.

Where is the man with all the money?

It’s cheap at half the price!

Who will buy this wonderful feeling?

I’m so high I swear I could fly

Me, oh my! I don’t want to lose it

So what am I to do

To keep a sky so blue?

There must be someone who will buy…’

Lionel Bart, Oliver!, 1960