Shumita Deveshwar- Director India research TS Loambrd writes in a note

“If the last major state elections being held just five months before the 2019 national polls can serve as a barometer, then Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reelection bid will be a tough race. We travelled last week through several parts of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan – two of the five states currently holding elections. At present, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is in power in those two states and is fighting head-to-head with the main opposition Congress. There is a real possibility of a BJP loss in all three states currently governed by the party in its Hindi heartland stronghold of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, and such an outcome will spook investors who have been counting on Modi’s re-election next year. The pace of implementation of the BJP’s myriad welfare and development programmes is frustratingly slow, causing voter discontent. Corruption at the lower levels of government and administration is rampant, while economic progress remains sluggish, with basic services such as good roads, water supply and teaching staff at government schools still lacking in many areas. Modi’s 2014 national election campaign motto of “Better Days” seems to be backfiring; his current campaign is negative, focused on attacking the opposition, rather than fighting on a pro-development plank. A BJP defeat in the state polls will likely increase pressure on Modi to ramp up spending with all the resulting macroeconomic risks and market volatility. A strong showing for the Congress will give it the momentum to form alliances with smaller, regional parties; a united opposition will likely prove a major challenge to the BJP in the national elections next year.

Modi eyes the national polls

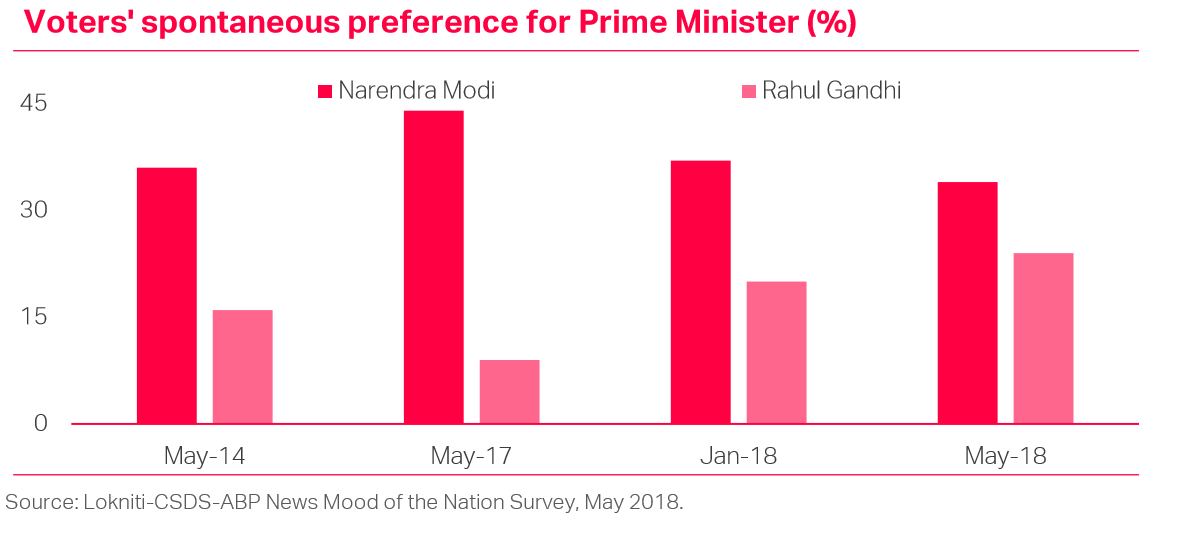

The Prime Minister’s emphasis on attacking the Gandhi dynasty suggests that his strategy for the 2019 general elections will be to pitch himself against Congress President Rahul Gandhi. As the chart below shows, Modi’s personal popularity far exceeds Gandhi’s, although the gap has been closing this year. State elections in India are often based on local and regional issues, such as how much connect the chief minister of a state has with the

people or a state legislature candidate has with the population of his or her own constituency. This was confirmed in our conversations with many voters as well as with local party leaders. Modi’s personal popularity will matter far more in the national elections.

The cost of a BJP defeat

The repercussions of a BJP defeat in the state elections currently under way will be serious, coming as they do just months before the national polls. For one, a BJP loss in more than two states will give the Congress a boost to rally regional parties around itself. An alliance of regional partners even helped defeat the BJP in its stronghold of Gorakhpur, the hometown of Uttar Pradesh (UP) Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, just a year after the ruling party swept the UP state elections in a landslide victory. Another major consequence of a big BJP defeat will be that the party will likely have a smaller number of seats from its Hindi heartland bastion in the April-May national polls. To some extent, voter discontent against the BJP in these state elections is likely to translate into a vote against the party in the national elections, too, despite Modi’s personal popularity. Since 2014, the year it came into power in New Delhi, the BJP has expanded its national reach, gaining control over 21 of India’s 29 state legislatures from just seven beforehand. The current state elections may signal the reversal of that trend. This will have implications for both houses of the parliament. In the lower house, where the BJP won a majority in the 2014 national elections, the party gained 62 of the 65 parliamentary seats up for grabs in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. By contrast, the BJP won only 30 of those 65 seats in the 2009 general elections with major losses in Rajasthan, where a Congress government had come to power in the 2008 state polls . To be sure, voting patterns in the state elections do not always match those of the national elections, but the BJP does need to do well in its traditional stronghold of the Hindi heartland to be able to return with a majority in the parliament. Furthermore, a loss in these states will reduce the BJP’s chances of gaining a majority in the upper house of the parliament as its representation in the state legislature determines the number of seats in the upper house to which it can nominate party members

The constant supply-demand mismatch

Even the BJP leaders we met in both states acknowledged the fact that fast-rising aspirations are not being met. “All the schemes announced by the government are incomplete,” said one BJP leader we met in the Rajasthan city of Kota. “Whoever you give a glass of water to, make sure you give him the full glass, and not half.” He was referring to the various development schemes, including the construction of toilets in poor households, for which the government provides funds.As we had found out in a Madhya Pradesh village that we had visited just one day earlier, toilets had been built for just a handful of houses and the women residents we spoke with complained of no water supply. “It is a toilet by name, not by function,” said one voter. The women also spoke of rampant corruption by administrators in the handing out of funds to construct the toilets. One woman in the village (located in the Narsinghgarh constituency, 80km northwest of Bhopal) protested against the bribe that the district level officers had demanded to issue voter identification cards for herself and her children. “We don’t have money to eat, there are no jobs, no factories here… how can we give money to get voter cards made?” she asked. “We have to give a commission for any work to be done,” said another woman who was standing next to her. Rural distress was glaringly obvious even though many observers acknowledge that Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Chouhan has tried to frame favourable policies towards farmers. However, food prices are low – as evidenced by persistently low food inflation, which, in turn, means that the returns for farmers for their crops are limited. Despite the sharp increase in minimum support prices for many crops announced by the Modi government earlier this year, none of the farmers we met seemed happy. At a wholesale agricultural market in ChachauraBinaganj, almost 70km further north of Narsinghgarh, farmers who had come to sell their produce said they were not getting good prices for vegetables and products such as garlic and coriander. On the other hand, many of the poor grumbled about the rise in fuel prices and other input costs that had left a hole in their pockets.

To be sure, some BJP supporters in the wholesale market credited the government for enabling funds to be transferred electronically and directly to their bank accounts. However, as we witnessed on the following day in Kolaras, another town close to the Madhya Pradesh-Rajasthan border, bureaucracy and the banks can break the trust of the people. One man we met said that getting money from the banks was not an easy process and hinted at corruption by bank officials. We decided to walk into a nearby branch of the State Bank of India, the country’s largest bank, which is also government-owned, to enquire why people face problems in getting their cash. The bank officials claimed it was due to technical problems, such as the way cheques are signed. Whatever the reason may be, voters seem unhappy with the way the state functions and this leads to frustration despite government efforts to improve efficiency and transparency. “People haven’t all got the benefits of the schemes,” said a BJP leader in nearby Shivpuri, even as she claimed that her party will still win the Madhya Pradesh election, albeit with a “wafer-thin

majority”. As we crossed over the border to Rajasthan, we found several more instances of voter discontent. In the village of Mundiya, people complained of negligible development, government schools that lacked teachers and limited employment opportunities that meant men had to travel to the city of Kota, 100km away, or even further to the state of Gujarat in order to find jobs. Indeed, the Rajasthan state poll seems to be a foregone conclusion with an overwhelming number of voters we spoke to saying that they will choose the Congress ticket. Even many of those who said they will vote for the BJP believed that the Congress will still form the government in the state. The margin of victory, however, will show whether it is a vote for the Congress or just a manifestation of anti-BJP sentiment in the states.

Conclusion

The ongoing state elections will determine whether Modi’s re-election bid in the AprilMay 2019 national elections will succeed easily or whether he will face a tough fight. A strong or even mixed outcome for the BJP – defined as a win in at least two of the three Hindi heartland states – will be welcomed by investors, as it will indicate that Modi’s party can overcome political headwinds. However, the findings from our visit to Madhya Pradesh suggest that the BJP may lose in that crucial state – even though the Congress requires a large vote swing in its favour to claim victory. With Rajasthan expected to go to the Congress and the buzz that Chhattisgarh, too, is likely to have voted out the BJP government, a 0-3 defeat for the BJP will be a shock to the markets. Moreover, it will lead to a serious rethink of poll strategies for the BJP, raising the risk of macroeconomic instability if it decides to ramp up welfare spending or political instability under pressure from Hindu hardliners in the party to try to turn voter attention to communal issues.

About T.S.Lombard (TS Lombard is a globally renowned independent research provider with a formidable 29 year track record in providing actionable investment ideas driven by unique understanding of economics, politics and markets. Our economic and political analysis drives our asset allocation recommendations which are both strategic and tactical. We also provide thematic equity calls through TS Lombard Research Partners. TS Lombard was formed through the merger of Lombard Street Research and Trusted Sources in August 2016. The merger has brought together two of the leading, and longest established, IRPs to create a unique offering combining best-in-breed macroeconomic forecasting and political and policy analysis. The group has a team of 25 analysts and strategists across offices in London, New York, Hong Kong, Beijing, Sao Paulo and New Delhi.)