by Apra Sharma

Tackling Income Inequality Requires New Policies

The hollowing out of the middle class, rising social and political tension, lack of education, globalization, and rapid technological change are just a few of the many drivers of growing income inequality.

“Inclusive growth is one of the critical challenges of our time,” IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said at a recent event on income inequality at the IMF Spring Meetings.

“The bitter-sweet reality is that despite economic growth there are still far too many people who are left out,” Lagarde added.

“If you look at advanced economies there’s certainly a trend towards an increase in inequality between 1990 and now,” she said. “But then when you look at emerging and developing economies, it’s more mixed.”

Though global income inequality has dramatically decreased, lifting millions out of poverty over the last several decades, inequality has risen dramatically within countries. For instance, the top one percent owns about half of the world’s wealth.

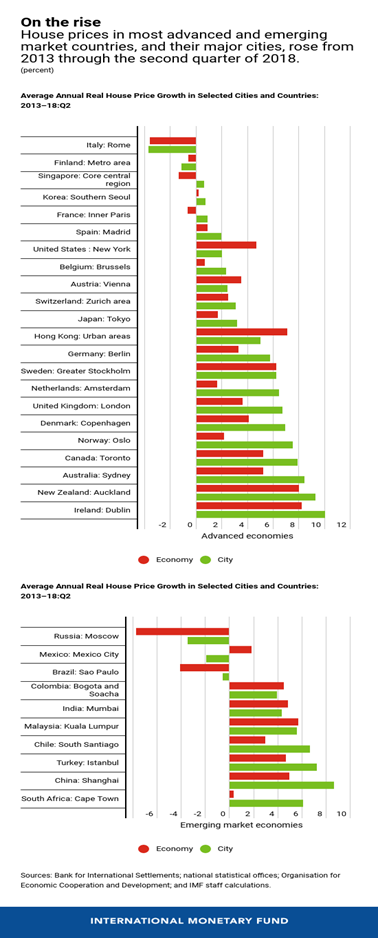

House Prices Are Up: Should We Be Happy?

IMF research shows that there is a tight link between movement’s in house prices, on the one hand, and economic and financial stability, on the other.

In fact, more than half of the banking crises in recent decades were preceded by boom-bust cycles in house prices. So it’s no wonder that central bankers in Australia, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere have expressed concern about the potential for large declines.

The Chart of the Week shows average annual price changes in 32 advanced and emerging market economies and their major cities from 2013 through the second quarter of 2018. Dublin tops the gains among major cities in advanced economies, at 10 percent. Among cities in emerging market economies, Shanghai takes the prize, with an annual increase of almost 9 percent.

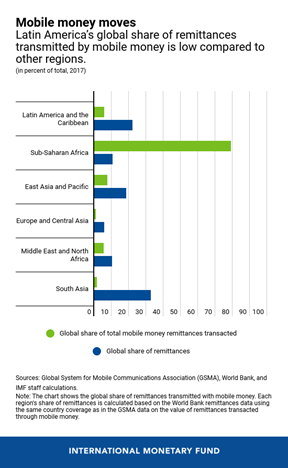

Fintech Can Cut Costs of Remittances to Latin America

For Latin Americans living abroad, sometimes sending money back home can be a complicated and costly ordeal. Most people rely on traditional banking methods and money transfer operators to send their remittances. But using these financial services for cross-border payments is costly—about a 6 percent charge on the total amount—and these fees are typically paid by the sender. This means less money left over for the family or friends receiving the money.

A more cost-effective approach for Latin American countries relies on using fintech, like mobile banking, to send money across borders, according to a recent IMF staff Working Paper.

Our chart of the week shows Latin America’s share of remittances transmitted with mobile money along with its overall share of remittances on a global scale. As the chart shows, Latin America’s use of mobile money both to send and receive remittances is relatively low—despite the region’s high share in total world remittances, which was about $80.5 billion in 2017. This stands in contrast to Sub-Saharan Africa, which is more advanced in using mobile money for remittances. Globally, Latin America’s share of remittances is larger than Sub-Saharan Africa’s share. But, as the chart shows, Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for the bulk of global mobile money remittance transactions, followed by East Asia and the Pacific.

According to the paper, mobile operators and mobile money can transmit remittances at a relatively low-cost, about 3 percent, compared to the cost of transfers using more traditional financial service providers, which is about 6 percent. Global Fintech companies are starting to partner with local mobile network operators, money transfer operators, and banks in the region to provide financial services. Across the region policymakers are already taking measures to improve the efficiency of payment systems. In addition, a supportive regulatory environment will be crucial to spur the development of Fintech solutions for remittance transfers in Latin America.

https://blogs.imf.org/2019/05/07/fintech-can-cut-costs-of-remittances-to-latin-america/