Ray Dalio writes in his LinkedIn Post https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/paradigm-shifts-ray-dalio/

One of my investment principles is:

Identify the paradigm you’re in, examine if and how it is unsustainable, and visualize how the paradigm shift will transpire when that which is unsustainable stops.

Over my roughly 50 years of being a global macro investor, I have observed there to be relatively long of periods (about 10 years) in which the markets and market relationships operate in a certain way (which I call “paradigms”) that most people adapt to and eventually extrapolate so they become overdone, which leads to shifts to new paradigms in which the markets operate more opposite than similar to how they operated during the prior paradigm. Identifying and tactically navigating these paradigm shifts well (which we try to do via our Pure Alpha moves) and/or structuring one’s portfolio so that one is largely immune to them (which we try to do via our All Weather portfolios) is critical to one’s success as an investor.

How Paradigm Shifts Occur

There are always big unsustainable forces that drive the paradigm. They go on long enough for people to believe that they will never end even though they obviously must end. A classic one of those is an unsustainable rate of debt growth that supports the buying of investment assets; it drives asset prices up, which leads people to believe that borrowing and buying those investment assets is a good thing to do. But it can’t go on forever because the entities borrowing and buying those assets will run out of borrowing capacity while the debt service costs rise relative to their incomes by amounts that squeeze their cash flows. When these things happen, there is a paradigm shift. Debtors get squeezed and credit problems emerge, so there is a retrenchment of lending and spending on goods, services, and investment assets so they go down in a self-reinforcing dynamic that looks more opposite than similar to the prior paradigm. This continues until it’s also overdone, which reverses in a certain way that I won’t digress into but is explained in my book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, which you can get for free here.

Another classic example that comes to mind is that extended periods of low volatility tend to lead to high volatility because people adapt to that low volatility, which leads them to do things (like borrow more money than they would borrow if volatility was greater) that expose them to more volatility, which prompts a self-reinforcing pickup in volatility. There are many classic examples like this that repeat over time that I won’t get into now. Still, I want to emphasize that understanding which types of paradigms exist and how they might shift is required to consistently invest well. That is because any single approach to investing—e.g., investing in any asset class, investing via any investment style (such as value, growth, distressed), investing in anything—will experience a time when it performs so terribly that it can ruin you. That includes investing in “cash” (i.e., short-term debt) of the sovereign that can’t default, which most everyone thinks is riskless but is not because the cash returns provided to the owner are denominated in currencies that the central bank can “print” so they can be depreciated in value when enough money is printed to hold interest rates significantly below inflation rates.

In paradigm shifts, most people get caught overextended doing something overly popular and get really hurt. On the other hand, if you’re astute enough to understand these shifts, you can navigate them well or at least protect yourself against them. The 2008-09 financial crisis, which was the last major paradigm shift, was one such period. It happened because debt growth rates were unsustainable in the same way they were when the 1929-32 paradigm shift happened. Because we studied such periods, we saw that we were headed for another “one of those” because what was happening was unsustainable, so we navigated the crisis well when most investors struggled.

I think now is a good time 1) to look at past paradigms and paradigm shifts and 2) to focus on the paradigm that we are in and how it might shift because we are late in the current one and likely approaching a shift. To do that, I wrote this report with two parts: 1) “Paradigms and Paradigm Shifts over the Last 100 Years” and 2) “The Coming Paradigm Shift.” They are attached. If you have the time to read them both, I suggest that you start with “Paradigms and Paradigm Shifts over the Last 100 Years” because it will give you a good understanding of them and it will give you the evolving story that got us to where we are, which will help put where we are into context. There is also an appendix with longer descriptions of each of the decades from the 1920s to the present for those who want to explore them in more depth.

Note: I have only reproduced below the second paradigm

Part 2: The Coming Paradigm Shift

The main forces behind the paradigm that we have been in since 2009 have been:

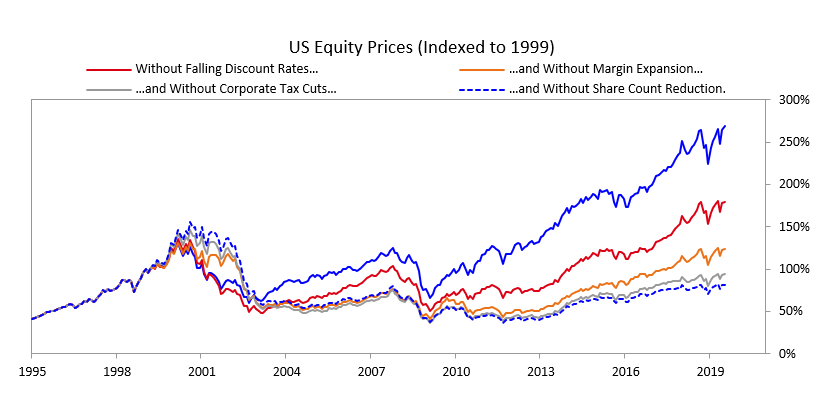

- Central banks have been lowering interest rates and doing quantitative easing (i.e., printing money and buying financial assets) in ways that are unsustainable. Easing in these ways has been a strong stimulative force since 2009, with just minor tightenings that caused “taper tantrums.” That bolstered asset prices both directly (from the actual buying of the assets) and indirectly (because the lowering of interest rates both raised P/Es and led to debt-financed stock buybacks and acquisitions, and levered up the buying of private equity and real estate). That form of easing is approaching its limits because interest rates can’t be lowered much more and quantitative easing is having diminishing effects on the economy and the markets as the money that is being pumped in is increasingly being stuck in the hands of investors who buy other investments with it, which drives up asset prices and drives down their future nominal and real returns and their returns relative to cash (i.e., their risk premiums). Expected returns and risk premiums of non-cash assets are being driven down toward the cash return, so there is less incentive to buy them, so it will become progressively more difficult to push their prices up. At the same time, central banks doing more of this printing and buying of assets will produce more negative real and nominal returns that will lead investors to increasingly prefer alternative forms of money (e.g., gold) or other storeholds of wealth.

As these forms of easing (i.e., interest rate cuts and QE) cease to work well and the problem of there being too much debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., pension and healthcare liabilities) remains, the other forms of easing (most obviously, currency depreciations and fiscal deficits that are monetized) will become increasingly likely. Think of it this way: one person’s debts are another’s assets. Monetary policy shifts back and forth between a) helping debtors at the expense of creditors (by keeping real interest rates down, which creates bad returns for creditors and good relief for debtors) and b) helping creditors at the expense of debtors (by keeping real interest rates up, which creates good returns for creditors and painful costs for debtors). By looking at who has what assets and liabilities, asking yourself who the central bank needs to help most, and figuring out what they are most likely to do given the tools they have at their disposal, you can get at the most likely monetary policy shifts, which are the main drivers of paradigm shifts.

To me, it seems obvious that they have to help the debtors relative to the creditors. At the same time, it appears to me that the forces of easing behind this paradigm (i.e., interest rate cuts and quantitative easing) will have diminishing effects. For these reasons, I believe that monetizations of debt and currency depreciations will eventually pick up, which will reduce the value of money and real returns for creditors and test how far creditors will let central banks go in providing negative real returns before moving into other assets.

To be clear, I am not saying that this shift will happen immediately. I am saying that I think it is approaching and will have a big effect on what the next paradigm will look like.

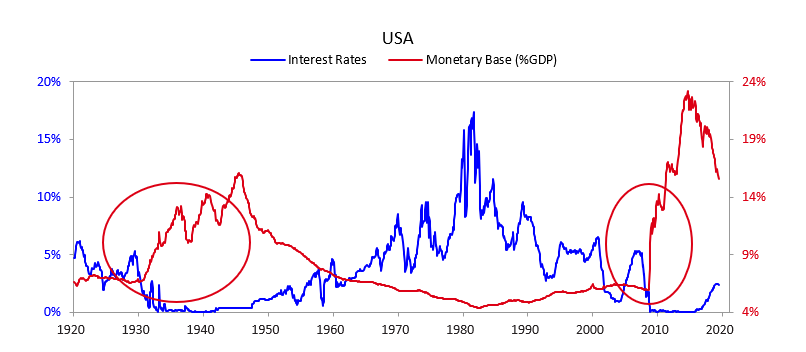

The chart below shows interest rate and QE changes in the US going back to 1920 so you can see the two times that happened—in 1931-45 and in 2008-14.

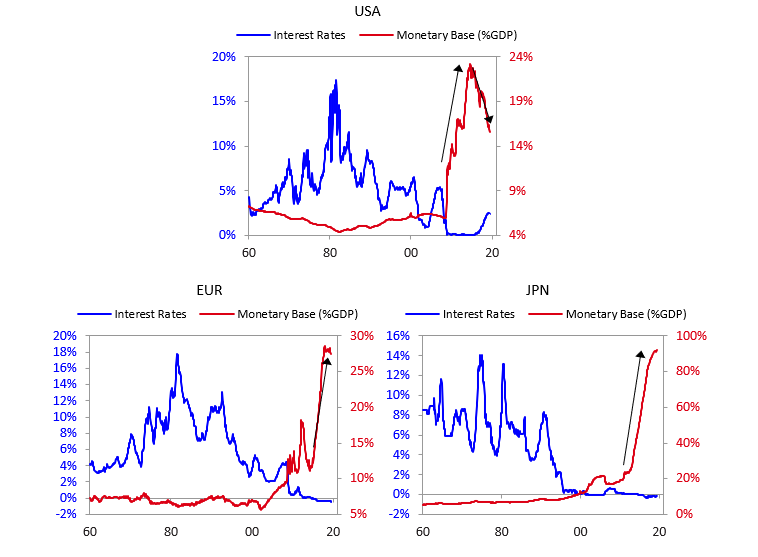

The next three charts show the US dollar, the euro, and the yen since 1960. As you can see, when interest rates hit 0%, the money printing began in all of these economies. The ECB ended its QE program at the end of 2018, while the BoJ is still increasing the money supply. Now, all three central banks are turning to these forms of easing again, as growth is slowing and inflation remains below target levels.

2. There has been a wave of stock buybacks, mergers, acquisitions, and private equity and venture capital investing that has been funded by both cheap money and credit and the enormous amount of cash that was pushed into the system. That pushed up equities and other asset prices and drove down future returns. It has also made cash nearly worthless. (I will explain more about why that is and why it is unsustainable in a moment.) The gains in investment asset prices benefited those who have investment assets much more than those who don’t, which increased the wealth gap, which is creating political anti-capitalist sentiment and increasing pressure to shift more of the money printing into the hands of those who are not investors/capitalists.

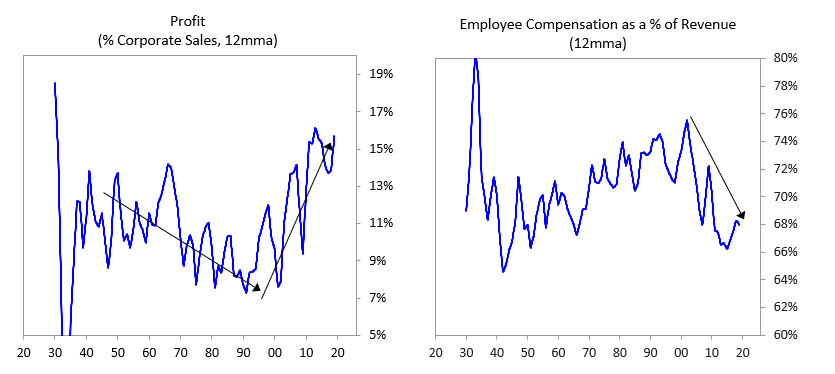

3. Profit margins grew rapidly due to advances in automation and globalization that reduced the costs of labor.The chart below on the left shows that growth. It is unlikely that this rate of profit margin growth will be sustained, and there is a good possibility that margins will shrink in the environment ahead. Because this increased share of the pie going to capitalists was accomplished by a decreased share of the pie going to workers, it widened the wealth gap and is leading to increased talk of anti-corporate, pro-worker actions.

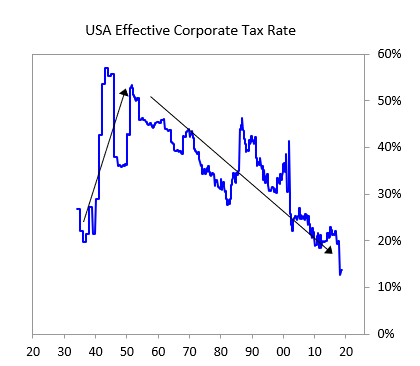

4. Corporate tax cuts made stocks worth more because they give more returns. The most recent cut was a one-off boost to stock prices. Such cuts won’t be sustained and there is a good chance they will be reversed, especially if the Democrats gain more power.

These were big tailwinds that have supported stock prices. The chart below shows our estimates of what would have happened to the S&P 500 if each of these unsustainable things didn’t happen.

The Coming Paradigm Shift

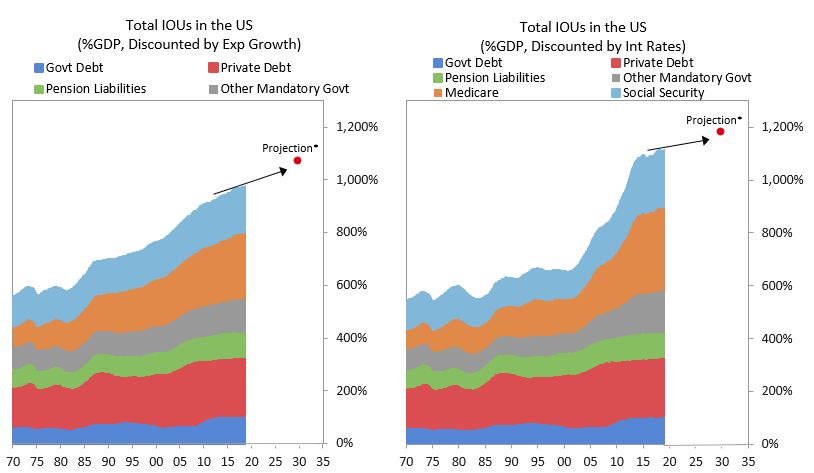

There’s a saying in the markets that “he who lives by the crystal ball is destined to eat ground glass.” While I’m not sure exactly when or how the paradigm shift will occur, I will share my thoughts about it. I think that it is highly likely that sometime in the next few years, 1) central banks will run out of stimulant to boost the markets and the economy when the economy is weak, and 2) there will be an enormous amount of debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., pension and healthcare) that will increasingly be coming due and won’t be able to be funded with assets. Said differently, I think that the paradigm that we are in will most likely end when a) real interest rate returns are pushed so low that investors holding the debt won’t want to hold it and will start to move to something they think is better and b) simultaneously, the large need for money to fund liabilities will contribute to the “big squeeze.” At that point, there won’t be enough money to meet the needs for it, so there will have to be some combination of large deficits that are monetized, currency depreciations, and large tax increases, and these circumstances will likely increase the conflicts between the capitalist haves and the socialist have-nots. Most likely, during this time, holders of debt will receive very low or negative nominal and real returns in currencies that are weakening, which will de facto be a wealth tax.

Right now, approximately 13 trillion dollars’ worth of investors’ money is held in zero or below-zero interest-rate-earning debt. That means that these investments are worthless for producing income (unless they are funded by liabilities that have even more negative interest rates). So these investments can at best be considered safe places to hold principal until they’re not safe because they offer terrible real returns (which is probable) or because rates rise and their prices go down (which we doubt central bankers will allow).

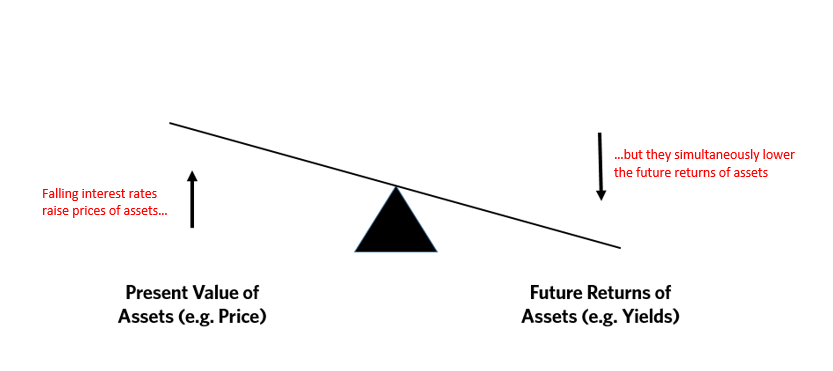

Thus far, investors have been happy about the rate/return decline because investors pay more attention to the price gains that result from falling interest rates than the falling future rates of return. The diagram below helps demonstrate that. When interest rates go down (right side of the diagram), that causes the present value of assets to rise (left side of the diagram), which gives the illusion that investments are providing good returns, when in reality the returns are just future returns being pulled forward by the “present value effect.” As a result future returns will be lower.

That will end when interest rates reach their lower limits (slightly below 0%), when the prospective returns for risky assets are pushed down to near the expected return for cash, and when the demand for money to pay for debt, pension, and healthcare liabilities increases. While there is still a little room left for stimulation to produce a bit more of this present value effect and a bit more of shrinking risk premiums, there’s not much.

At the same time, the liabilities will be coming due, so it’s unlikely that there will be enough money pushed into the system to meet those obligations. Then it is likely that there will be a battle over 1) how much of those promises won’t be kept (which will make those who are owed them angry), 2) how much they will be met with higher taxes (which will make the rich poorer, which will make them angry), and 3) how much they will be met via much bigger deficits that will be monetized (which will depreciate the value of money and depreciate the real returns of investments, which will hurt those with investments, especially those holding debt).

The charts below show the wave of liabilities that is coming at us in the US.

*Note: Medicare, Social Security, and other government programs represent the present value of estimates of future outlays from the Congressional Budget Office. Of course, some of the IOUs have assets or cash flows partially backing them (like tax revenue covering some Social Security outlays). 10-year forward projections are based on government projections of public debt and social welfare payments.

*Note: Medicare, Social Security, and other government programs represent the present value of estimates of future outlays from the Congressional Budget Office. Of course, some of the IOUs have assets or cash flows partially backing them (like tax revenue covering some Social Security outlays). 10-year forward projections are based on government projections of public debt and social welfare payments.

History has shown us and logic tells us that there is no limit to the ability of central banks to hold nominal and real interest rates down via their purchases by flooding the world with more money, and that it is the creditor who suffers from the low return.

Said differently:

The enormous amounts of money in no- and low-returning investments won’t be nearly enough to fund the liabilities, even though the pile looks like a lot. That is because they don’t provide adequate income. In fact, most of them won’t provide any income, so they are worthless for that purpose. They just provide a “safe” place to store principal. As a result, to finance their expenditures, owners of them will have to sell off principal, which will diminish the amount of principal that they have left, so that they a) will need progressively higher and higher returns on the dwindling amounts (which they have no prospect of getting) or b) they will have to accelerate their eating away at principal until the money runs out.

That will happen at the same time that there will be greater internal conflicts (mostly between socialists and capitalists) about how to divide the pie and greater external conflicts (mostly between countries about how to divide both the global economic pie and global influence). In such a world, storing one’s money in cash and bonds will no longer be safe. Bonds are a claim on money and governments are likely to continue printing money to pay their debts with devalued money. That’s the easiest and least controversial way to reduce the debt burdens and without raising taxes. My guess is that bonds will provide bad real and nominal returns for those who hold them, but not lead to significant price declines and higher interest rates because I think that it is most likely that central banks will buy more of them to hold interest rates down and keep prices up. In other words, I suspect that the new paradigm will be characterized by large debt monetizations that will be most similar to those that occurred in the 1940s war years.

So, the big question worth pondering at this time is which investments will perform well in a reflationary environment accompanied by large liabilities coming due and with significant internal conflict between capitalists and socialists, as well as external conflicts. It is also a good time to ask what will be the next-best currency or storehold of wealth to have when most reserve currency central bankers want to devalue their currencies in a fiat currency system.

Most people now believe the best “risky investments” will continue to be equity and equity-like investments, such as leveraged private equity, leveraged real estate, and venture capital, and this is especially true when central banks are reflating. As a result, the world is leveraged long, holding assets that have low real and nominal expected returns that are also providing historically low returns relative to cash returns (because of the enormous amount of money that has been pumped into the hands of investors by central banks and because of other economic forces that are making companies flush with cash). I think these are unlikely to be good real returning investments and that those that will most likely do best will be those that do well when the value of money is being depreciated and domestic and international conflicts are significant, such as gold. Additionally, for reasons I will explain in the near future, most investors are underweighted in such assets, meaning that if they just wanted to have a better balanced portfolio to reduce risk, they would have more of this sort of asset. For this reason, I believe that it would be both risk-reducing and return-enhancing to consider adding gold to one’s portfolio. I will soon send out an explanation of why I believe that gold is an effective portfolio diversifier.