By Michael. A . Gayed CFA

Summary

COVID-19 has acted as a ‘Great Accelerator’ to many pre-existing socioeconomic and technological trajectories.

Trends in monetary and fiscal policy have also been accelerated. Not only in the amount of stimulus but also in merging the two forms of policy.

In many ways, merging the two is necessary, given that the historic reliance on monetary tools has left the real economy struggling while asset prices have rebounded.

A powerful narrative has emerged in the wake of COVID-19. ‘The Great Acceleration’ is the concept that previously existing socioeconomic developments have been pushed into overdrive. Tele-commuting, the dominance of big-tech, and the shift to online learning have all taken multi-year jumps forward in the space of just months. For instance, NYU Stern Professor Scott Galloway explains that post-secondary education models are permanently shifting here.

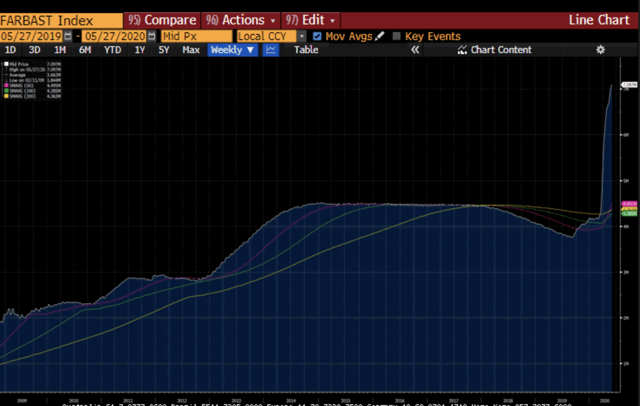

The economic fallout from COVID-19 has also provided new fuel for the prevailing trends in monetary and fiscal policy. The Fed has expanded its balance sheet by around $3 trillion in around 90 days.

Even before COVID-19 appeared, monetary easing was already ongoing. The Federal Reserve cut overnight rates three times before the global pandemic shocked the world (July, September and October of 2019). The ferociousness of the Fed’s response to the virus indicates that policymakers believed that liquidity conditions were tight, despite a 1.5% Fed Fund rate pre-virus.

Policy, Currencies, And Credit

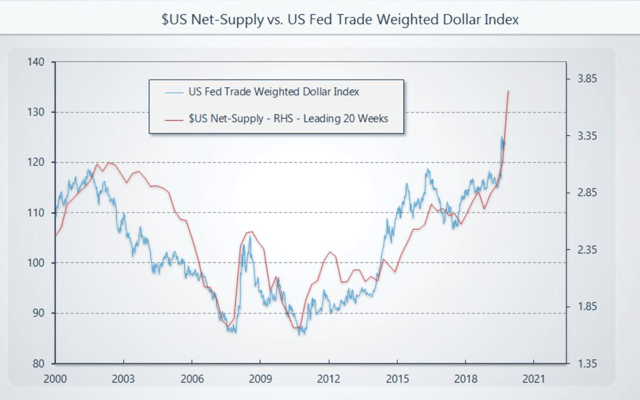

A strengthening USD amidst a growing Fed Balance Sheet has been a hallmark of the post-GFC period. This is somewhat counterintuitive to traditional economic doctrine. The rapid balance sheet expansion in March accelerated the post GFC trend. Below is a chart of net USD supply (M2 – Total US Denominated Debt) compared to the Trade Weighted Dollar Index.

Source: GMI

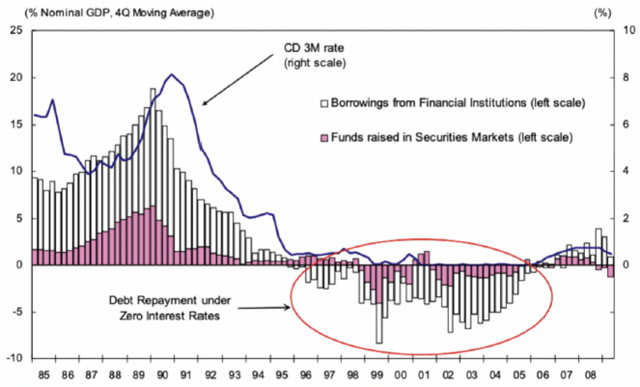

One explanation for this relationship is that through Quantitative Easing (QE), the money supply sits as excess reserves at institutions, while borrowing demand remains weak. Smaller entities that need dollars have a hard time getting them from banks. Larger, formerly highly-indebted companies focus on de-leveraging. This was a hallmark of Japan’s ‘lost decade’ through the 1990s.

Source: Bank of Japan

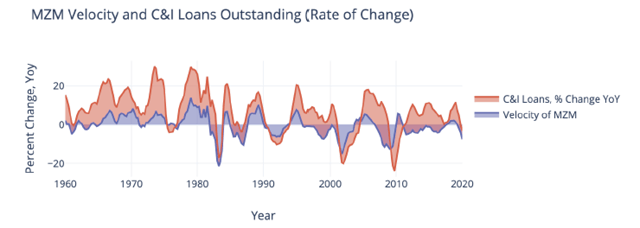

As monetary policy becomes easier, the velocity of money decreases. Central bank balance sheet expansion through QE and asset purchases increases asset prices but does not stimulate corporate capital expenditures. Below is a graph of U.S. money velocity as compared to commercial and industrial (C&I) loans outstanding.

Source: St. Louis Fed, BIS

The Japanese experience through the 1990s was somewhat different in the sense that the Yen did not carry the same global reserve currency status that the USD maintains. The offshore dollar borrowing market (Eurodollar market) has exploded in size over the past decade. This is the classic currency carry trade – the USD as a funding market for offshore recipient markets.

The market liquidity event through March caused massive stress in offshore dollar funding markets. As U.S. policymakers announced an unprecedented $7 trillion in monetary and fiscal stimulus through March and April, the trade-weighted dollar was unchanged over that period. This indicates how short of dollars global markets have been for years, punctuated by a liquidity event that exacerbated the prevailing trend.

The Next Chapter

So long as the U.S. dollar maintains strength, it’s likely that policymakers continue with massive fiscal and monetary initiatives to address the economic fallout from COVID-19. Policymakers would prefer a lower dollar, but the past ten years have shown the disconnect between dovish policy and the dollar.

The disconnect between market prices and the real economy is historic. The importance of fiscal policy to restore employment and consumer spending cannot be understated. The distinction between monetary and fiscal policy has effectively shrunk. As the U.S. Treasury issues stimulus cheques to individuals funded by Treasury bond issuances and the Fed purchases these securities through open market operations, we’ve crossed a bridge into MMT.

Difficulties in walking back balance sheet expansion were illustrated by the Q4/18 rejection of Powell’s quantitative tightening (QT) program. Given massive headwinds in employment, it will be incredibly challenging for policymakers to consider reductions in fiscal stimulus. If anything, policymakers will likely err on the side of more, rather than less.

The most prominent effect of stimulus is not CPI inflation, dollar weakness, or material increases in economic growth. Instead, it’s an appreciation in asset prices. The Fed is incentivized to continue to stimulate asset prices further.

Unfortunately, a major consequence of asset price inflation is the exacerbation of wealth inequality. This was traditionally due to ownership of assets being increasingly concentrated in the hands of the wealthy. Now we face another source of income equality: the benefactors of new economic stimulus being disproportionally large businesses while Main Street does not have the same access to capital. This was observed in Japan in the 1990s, and already there are signs of the same trend in the U.S.

In Conclusion

The reliance on monetary policy as a stimulus tool has accelerated through the coronavirus epidemic, just like many other trends across society. The emergent phenomena of combining fiscal and monetary policy is also making a surge forward.

This combination is necessary given the disconnect between asset prices and the state of the real economy. History suggests that businesses prefer to de-lever rather than borrow after facing insolvency scares. Policymakers have much more experience in monetary expansion compared to directly injecting capital into individuals’ bank accounts. The transmission mechanisms for the former are tried and tested, whereas the implementation of policies resembling MMT is embryonic.

The widening gap between the well-being of the average American and the level of asset prices adds to the palpable state of societal unease, particularly among low-income earners. Policymakers understand this, and I would expect a massive fiscal response. However, these tools are new and less battle-tested than monetary policy, which will also continue to be used heavily. The implications for further monetary expansion are easier to see (higher asset prices) than an acceleration in monetization of fiscal deficits. But it’s hard to imagine that the usage of both sets of tools will not continue to accelerate at breakneck speed.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4351530-great-accelerator-dollar-credit-and-stimulus