The Growth model for less developed economies for the past two decades was to leverage global demand by utilizing cheap and abundant labor resources and attracting foreign capital and technological knowhow.

It was globalization of the 1850s-1910s that was underwritten by the British capital, industry and navy that offered an opportunity for the US and Germany. By 1913, the level of globalization reached levels that were not again surpassed until the 1990s. Hence, the frequent arguments in 1909-13, that a war in such a globalized world was impossible to contemplate. Th at prediction turned out to be disastrously wrong. The next major globalization phase started in the 1970s but significantly accelerated in 1980s-90s and peaked just before GFC in 2007. This period provided the necessary boost for Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and of course China, and in a different way, Israel and to some extent Thailand and Malaysia. Alas, as discussed in our past notes, this latest period of globalization has now gone into reverse.

The rhetoric has now changed and shifted towards favouring local interests over globalisation.

Similar to the currency trilemma, one cannot have nation states, local politics and globalisation at the same time. Nation states and local politics seems unlikely to disappear and thereby what will be affected is globalisation.

So, globalisation will reverse and create winners and losers. The winners are unlikely to compensate the losers in an acceptable time frame. Losers tend to concentrate in certain geographies, occupations and racial groups.

In view of the current technological, financial and demographic environment, globalisation is set to reduce further and accelerate the atrophying of supply chains while removing development opportunities for emerging and developing economies.

So the options for Emerging Markets to accelerate their per capita gdp growth rates are

- Size of Domestic Market

Size of local domestic market increases in importance thereby China and India will be at an advantage vis – a-vis Malaysia or Thailand.

- Ability of Emerging Market countries to restart respective business cycles –

The ability to combine fiscal and monetary policy to restart domestic cycle depends on level of monetary sovereignty, quality of state institutions, supply side bottlenecks and capacity utilization flexibility.

- Ability to improve efficiency of non-tradeable sectors and provide structural reform to remove rent seeking vested interests.

- Emerging Markets ability to embrace the intangible sector as tangibles sector decline. This will require intellectual capital. Building intangibles requires careful nurturing for long time periods.

The above challenges are accelerated by the compounding of significant demographic changes.

In an Industrial age, demographics and urbanisation can become productivity and wealth enhancers. In this world, increase in size of young people accompanied with improvement in human capital and Core infrastructure growth led to growth.

In the new world, where key to productivity growth are no longer humans as need for labour input decreases as proportion of gains from intangible assets rise. The rise on young cohorts and urbanisation would increasingly be associated with poverty, squalor and disease.

Thus, in the Information Age, rapidly rising younger cohorts will likely lead to lower per capita income, less growth and more violence. On the other hand, an ageing population might not excessively strain budgetary or financial systems, as technology and greater fiscal flexibility change this dynamic.

Having fewer people especially young people becomes a positive demographic trend.

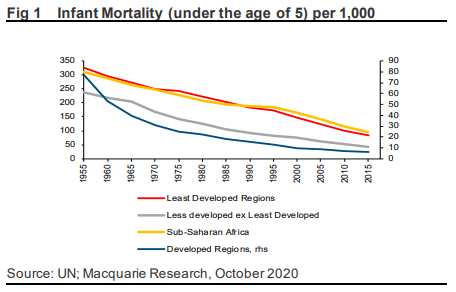

The collapse in infant mortality rate in emerging and less developed countries is causing a significant explosion of populations across emerging market countries.

Emerging market population under 15 is likely to exceed 1.8 Bn with most growth coming from outside of China, with Ems ex China cohort passing 1.5 Bn.

On the other younger cohort is going to drop below 200 Mn in more developed economies.

According to the UN database, EMs ex China labour force is likely to grow by 0.5bn in the next ten years and by almost 1bn over twenty years. It is estimated that by 2040, ~72% of the global labour force will be based in less developed economies, excluding China vs 55% in 1990 and 60% in 2010. In other words, less developed economies ex China need to create more than 45m jobs pa.

The avenues for deploying a bulge in working population is being gradually shut down.

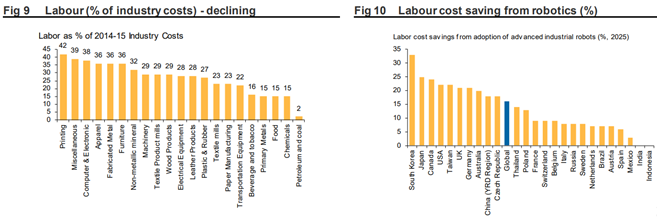

Manufacturing employs a large number of low to mid skilled people which Emerging markets have in abundance. Manufacturing also leverages global demand as compared to local demand. Manufacturing also has one of the largest domestic economic multiples i.e. an estimated $3 for every $ of manufacturing.

Technology coupled with anti-globalisation sentiment has reduced the importance of merchandise trade compared to value of services, technology & intellectual capital.

In the last decade non-tariff barriers along with robotics and automation is on the rise. This is reducing demand for labour in labour intensive industries at a time when there is an even more urgent need of jobs.

These trends are already visible, even before full merger of cloud computing, AI and 3D printing, which will further accelerate disintermediation of the supply and value chains while eliminating a large portion of factories and significantly simplifying every product, with production and consumption increasingly residing in the same place.

The importance of services, intangibles compared to merchandise trade is rising.

Services now constitute as much as 1/3 of what is today classified as merchandise trade. If adjusted for the value of digital and intangible services, it is likely that the overall value of services already exceeds value of merchandise trade, even though in purely reported terms, merchandise is ~2.5x larger.

Intangibles do not have the same capacity limitations as tangible assets and offer significant synergies and spill-over effects while maintaining higher pricing power and delivering sustainably higher returns.

It is intangibles that are now the driver of growth and wealth as pricing power and value of tangible assets erodes.

Countries relying on cheap labour and basic commodities will fall behind countries that rely on intellectual capital and intangible assets.

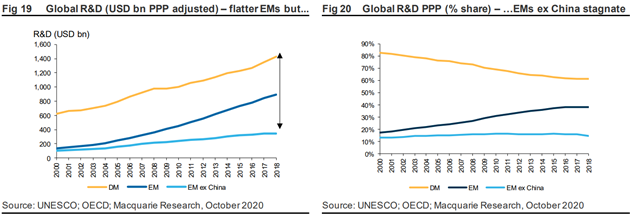

Emerging Markets have relatively less access to intellectual and intangible assets. R&D spending in Emerging markets excluding China is around $130 Billion representing 7% of the worlds total.

At the same time more than 75% of R&D spending globally is spent in developed economies. China has increased its share from 2% in 2000 to 17% in 2018.

In 2017, the less developed economies excluding China had only 3% of the global patents as compared to 85-90% belonging to developed economies. Meanwhile, China’s share increased to 8% from negligible in the year 2000.

Less developed economies, excluding China, currently have just over two million researchers or ~25% of the global total. This compares to almost 2m researchers in China alone, around 2.5m in the EU-28, almost 1m in Japan and 0.5m in Korea.

In most developed economies at least 35%-50% of the private sector GDP is now driven by intangible assets, with the US at the highest level at more than 60%. However, in less developed economies ex China, it appears that intangibles do not exist in any meaningful form. Even in China, estimates point to intangibles being perhaps not much more than 10%-15% of private sector GDP.

The main issue to contend is that currently approximately 2/3 of the worlds population has too much labour which is becoming less important as compared to the resources required for success in the future i.e. intellectual and intangible information age assets.

With, Emerging markets unable to accelerate GDP per capita growth rates significantly over last 6 decades, the future is even more treacherous. Other than a massive Marshall Plan like policy response it is hard to see any other measure that would unleash uncontrollable immigration, social, geopolitical, and healthcare pressures.

Is China in a class of its own ?

The growing deglobalization and technological disintermediation when combined with political backlash against globalization in more developed economies and the rise of geopolitical pressures seem to suggest that China might transit from being the greatest beneficiary of globalization to becoming its most significant loser.

However, the new information age will favour countries with a significant domestic market and no emerging market comes close to China’s US$5-6 Trillion domestic consumption.

The new Information Age also requires a much greater reliance on local fiscal and monetary pulses. China is the only EM that has already been practising a version of MMT while liberally mixing fiscal and monetary levers.

China has the right demographics for the New Age. China’s under 15-year-old cohort peaked in the late 1970s-early 1980s at around 370m. Today, it stands at 255m and is expected to drop to ~200m by 2040. Hence, China has benefited from a massive rise in the working age cohorts through 1980s-00s, but the labour force peaked in 2015 and should drop to ~890m by 2040.

Increasingly productivity is derived not from labour or tangible assets but from intangibles. Thereby, China has relatively less pressure to generate high number of good paying jobs.

China is the only major developing economy that is succeeding in building a broad range of intellectual and intangible assets. China is already responsible for 17% of global R&D spending. It is also employing more than 20% of global researchers and has become the leading publisher of cross-referenced scientific publications while its internationally recognized patterns now account for ~8% of the global pool vs nothing in 2000.

It is not surprising therefore that the new economy now accounts for more than 50% of MSCI China while these sectors are also responsible for the highest ROE’s and the greatest profit generation.

China still does face a myriad of challenges.

Most of China’s R&D as well as patents (over 60%) are mostly small incremental improvements rather than brand new breakthroughs. In other words, China is much better at innovation rather than inventiveness, and it continues to heavily depend on the bank of Western intellectual breakthroughs.

China lacks independent institutions and is heavily centralised, while developed countries are moving in the same direction, they are still much more independent. This clash between the Anglosphere and Sinosphere is still to play out yet and it is to be seen how China navigates through these complexities.

As the world atrophies into sinocentric and other global value chains, the only feasible response is for China to create and effectively ring-fence its own sphere of influence while emphasizing the domestic economy.

China will need to invest even more aggressively in robotics and automation. Thus, one of the key challenges facing China is to redefine and strengthen its welfare and social policies while massively expanding its current modest basic income guarantee schemes.

China has the tool kit to manage this transition, as long as the geopolitical tensions are kept under a degree of control. Most importantly, it has monetary sovereignty and extensive experience of mixing fiscal and monetary policies, and indeed, for decades it has already practiced MMT. China also remains highly competitive across a range of industries, including many labour intensive and low value added segments, while it is growing an impressive Information Age footprint.

Thereby, the investable universe for Emerging markets had already shrunk to China, a bit of India and a few themes in Brazil. The other countries are cyclical proxies and even if the right corporates are invested in , many of these countries will suffer long term depreciation.

However, unless political and geopolitical tensions are contained, ESG and societal demands, might increasingly make China uninvestable for most investors.

As we move away from a world characterized by ‘freedom, choice and inefficiency’ towards ‘equality and fairness’, previously acceptable practices such as exuberant CEO compensation, excessive share buybacks, polluting the environment, engaging in uncontrolled surveillance or running labour camps will be heavily penalised. It is therefore possible that an increasing number of China’s stocks and sectors might be ‘blacklisted’, not by the US State Department, but by ESG and societal norms, turning China into effectively an off-index market. While most investors argue that one cannot ignore the world’s second-largest market, we disagree. It can be ignored, and indeed, even China might eventually view it as the best ‘dual circulation’ outcome.