Covid came as a shock to the world, but in many cases it is merely accelerating fundamental trends that were already unfolding anyway. The US-China rift, the debasement of western currencies, the de-dollarization of emerging markets, the attempts to replace carbon energy with renewables, the increase in social tensions linked to living in multicultural societies: everything now seems to have gone into hyperdrive.

This probably shouldn’t be a surprise. If there has been one constant theme in Gavekal’s research over the last 15 years or so, it is that we are living in an age of accelerating creative destruction. This idea is the common thread that ties together the books Charles and I have written, from Our Brave New World, through A Roadmap For Troubling Times, to Clash Of Empires, and it is one most clients seem happy to agree with.

And this forces us face-to-face with an almighty capital allocation paradox. As the world changes at an ever-increasing rate, and the future becomes ever more challenging, more and more money pours into private equity funds and other forms of locked-up investments. This is odd. In a world in which the future is increasingly uncertain, surely investors should be avoiding illiquid strategies like the plague, and instead falling over each other to seek shelter in the financial industry’s more liquid offerings? Instead, we are seeing precisely the opposite.

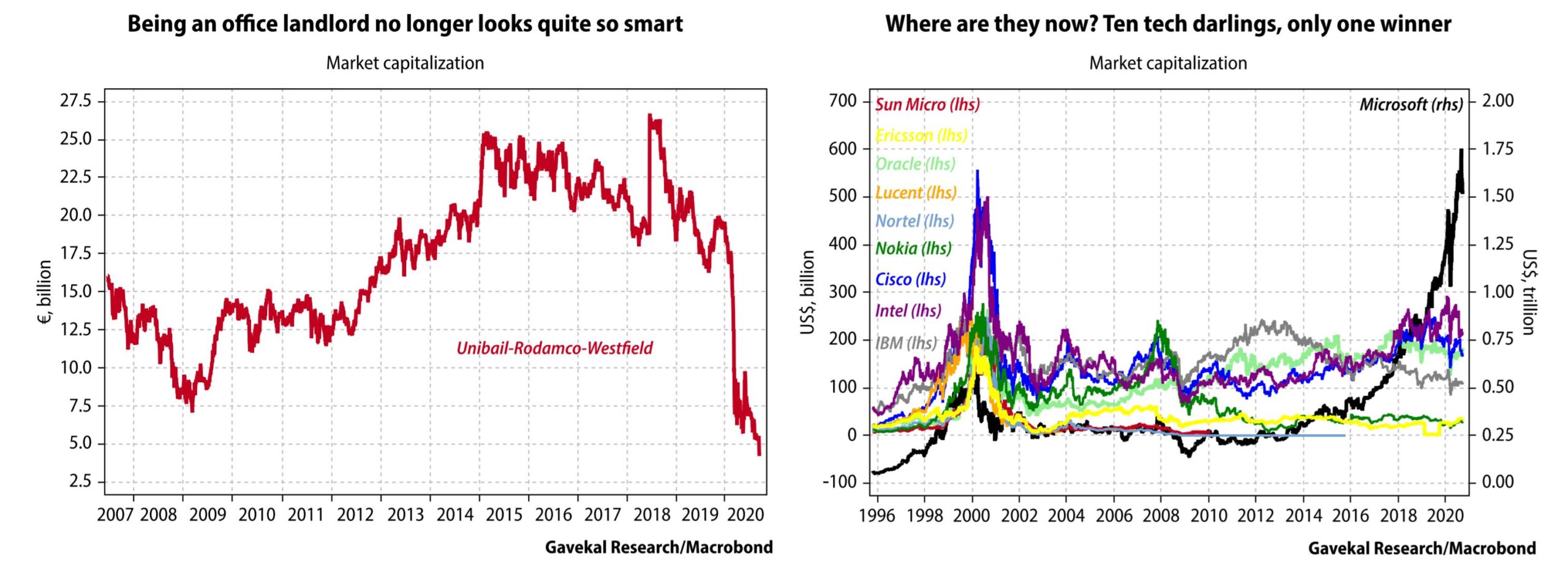

To take one example: a year ago, owning an office building in Midtown Manhattan, London’s Canary Wharf or downtown San Francisco might have seemed as “safe as houses”. But in the age of the unexpected, what was a sure bet yesterday can turn into a certain loser today. Just look at UnibailRodamco-Westfield, one of Europe’s largest office and commercial property landlords. In two years, it has seen its market capitalization collapse from €27bn to €4.2bn. Two years ago, owning commercial and office space seemed like a good idea. Today, it is toxic.

Alternatively, consider an investor who in January 2000 decided that new technologies were bound to change the way we live, work and play, and that the way to play this change was to put capital into the 10 tech companies with a market cap at the time of over US$200bn (figuring that size and scale would be the key drivers of long-term performance). Our investor would have bought Microsoft, Oracle, Intel, IBM, Cisco, Lucent, Ericsson, Nokia, Sun Microsystems and Nortel Networks.

Reinvesting all his dividends, he would have ended up two decades later with one winner (Microsoft), three washes (Oracle, Intel and IBM), three big disappointments (Cisco, Nokia and Ericsson) and three donuts (Lucent, Sun Micro and Nortel). His total compound annual growth rate (dividends included) would have been 1.4%. And he would have missed out on the likes of Amazon (with a November 1999 peak market cap of US$35bn) and Apple (US$23bn in March 2000).

Clearly, in a single generation, the tech world has changed almost beyond recognition, and the companies which offered scale 20 years ago mostly failed to cope with that change despite all the advantages of size (or perhaps because of them?).

This makes investors’ enthusiasm for illiquidity all the more strange. Why, in a world that is changing so fast, would investors rush headlong into illiquid strategies? Why should they so readily give up the opportunity to say: “The world is changing. My portfolio needs to evolve?”

There are two possible reasons: extra income, and extra growth.

In a world in which income is ever-harder to find, giving up liquidity (especially for those who do not need it immediately) in exchange for extra income might seem to make a lot of sense. However, more often than not, the excess income is delivered by gearing up balance sheets. And increasing leverage typically increases fragility. In a time of accelerating creative destruction, rapid societal shifts and growing geopolitical uncertainty, does increasing fragility (by increasing leverage) really make sense?

Gearing up balance sheets might make sense in an environment of structurally falling interest rates. As interest rates fall, asset prices get rerated and the value of equity increases rapidly. Of course, this cuts both ways: once interest rates stop falling and either flatline or rise, gearing, instead of boosting shareholder returns, begins to destroys them.

Not that rising interest rates are needed to destroy shareholder returns. Think again of a hypothetical Canary Wharf* landlord: gearing up the balance sheet to buy buildings whose yields were higher than the interest rates charged seemed like a no-brainer. Then Covid-19 hit, and rent payments stopped. Very quickly, the equity in the business was facing a wipe out. In this context, shouldn’t the Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield faceplant raise questions over the value of the equity in a whole swathe of real estate private equity funds?

I could go on, but it suffices to say that with interest rates at record lows and with the world changing ever more rapidly, accepting illiquidity in return for the promise of increased income seems like a dangerously shortsighted proposition. Once again, investors are picking up pennies in front of steamrollers.

This leaves the prospect of growth as the only reason to accept illiquidity. This can make excellent sense: investors offering entrepreneurs both capital and time to succeed is what capitalism should be all about. And in a world that changes ever more rapidly, the entrepreneur who can adapt, safe in the knowledge that he is backed by investors that are not pressed for time, has an important competitive advantage.

It follows that when looking at the illiquid strategies institutional investors have poured capital into over recent years, there are two key questions to ask:

- Is the competitive advantage of this strategy derived from some kind of financial engineering?

- Or does the competitive advantage of this strategy flow from the ability to identify entrepreneurs and business leaders who need capital?**

In a world that is changing ever more quickly, the first type of strategy will become ever riskier. Meanwhile, in a properly functioning capitalist system, investors who are successful at implementing the second type of strategy will continue to be rewarded very handsomely indeed.

https://blog.evergreengavekal.com/illiquidity-and-creative-destruction/