The turmoil in technology stocks continues. Since early September, the Nasdaq 100 has corrected almost 13%. Heavyweights like Apple, Amazon and Facebook lost around 18%.

Gavin Baker knows how to keep a cool head in difficult situations like these. The founder of the US investment firm Atreides Management has been investing in technology companies for twenty years and ranks amongst the most renowned investors in the sector.

His core strengths include investments in semiconductor stocks like Nvidia, Intel or Micron Technology. «In the past, the semiconductor industry has gone through three negative demand shocks. Now, we have a positive demand shock in the form of artificial intelligence,» says Mr. Baker during an interview via Zoom from his company headquarters in Boston.

In this in-depth interview with The Market/NZZ, Mr. Baker explains what it takes to be a successful investor, why semiconductors become ever more important for the global economy and what the tech war between the US and China means for the industry. He also explains why he wouldn’t write off Intel despite recent production issues with its next-gen processors.

Mr. Baker, after the phenomenal run since the lows of March, technology stocks are experiencing some weakness. What’s your take on the current market environment as a veteran tech investor?

For the last forty years, technology has consistently been the most alpha-rich sector. This means there are always a lot of opportunities. Because of the pandemic, many technology companies were certainly accelerated this year. In many ways, Covid has pulled the world into the years between 2025 to 2030 which has resulted in some pretty spectacular moves for some stocks. But now, a lot of these stocks are at valuations that are historically quite extreme – and valuation actually always does matter. On the other hand, a lot of the big names that are driving the market are trading at less than 30x earnings. In the context of ten-year interest rates under 1% that’s not an aggressive multiple.

How can investors navigate today’s challenging environment?

To succeed as an investor, you have to be able to deal in paradoxes. You have to find the right balance between conviction and flexibility, between arrogance and humility: The arrogance to believe you can have a differentiated view on a stock in such a competitive market, and the humility to recognize that you could be wrong. As a technology investor in particular, you have to balance imagination with reality. You have to find the right balance between enthusiasm and dispassion. You also have to be very knowledgeable. What’s more, tech and consumer have kind of merged as a sector. For example, how can you look at Amazon and not study Walmart? How can you look at Airbnb and not be intimately familiar with Marriott and Hilton? All these businesses are merging in profound and important ways, and the lines between tech and consumer are blurring.

What does this mean for future investment returns in tech stocks?

It is a very interesting time in technology. Truth, valuation, interest rates and probability are gravitational forces for stocks. But trends in Free Cash Flow and Return on Invested Capital are quantum forces. One of the most fascinating things is that in the past, ROICs were highly mean reverting: Companies with high returns would generally see those returns mean revert over time. That stopped being true roughly fifteen years ago. Since then, high ROIC companies are maintaining those returns and they are showing no sign of falling.

How come?

I think it’s because of technology. Traditionally, we used to think about a natural monopoly of being a business with high fixed costs and extremely low variable costs. That’s why it makes sense to have only one cable, pipeline or railroad system because the costs of building these networks are so high. But today, a lot of these mega cap technology companies are natural monopolies of an entirely new kind the world has never seen – and that means they are much tougher to compete with.

Why are these companies a new kind of monopoly?

If you’re willing to spend enough capital, you can recreate the railroad systems in America with $500 billion. With a lot of money, you can also build a new cable system or a new electric or gas utility network. FedEx and UPS have shown us that you can recreate the postal system. But you actually cannot spend any amount of money and create a search engine that is better than the world’s dominant search engine today. People have tried: Amazon had an internal effort to build a search engine, and they concluded it was impossible. Microsoft has worked at Bing for many years and never really gained market share. The reason is that with any product where the quality is driven by artificial intelligence, it’s almost impossible to compete with the market leader.

What’s the reason for that?

To improve the quality of AI, you have to increase the amount of data you use to train the model. In essence, if you train an algorithm with 10x the data, the quality of the algorithm doubles. So you get these feedback loops: If you have a great product like a search engine, more people use it, you get more data, the product gets better, even more people use it and so forth. That fly wheel just spins and this is why it’s hard to replicate Google. It’s a game of cumulative knowledge and data. The primacy of data for AI quality means that some of these companies are truly unique because their competitive advantage is not just growing every year, it’s literally growing every second. Those are great dynamics for investors, but for society they create very difficult trade-offs: How do you regulate these monopolies? Do you regulate them in such a way that the product gets worse?

How does this impact a sector like semiconductors which propel artificial intelligence and the digital transformation of the world in general?

In the past, the semiconductor industry has gone through three negative demand shocks. Around eighteen years ago, the world’s most powerful computers were not utilized most of the time, meaning a lot of memory and microprocessor capacity was sitting idle. So the first negative shock was virtualization which helped to utilize servers much more efficiently. The next shock, at the beginning, was cloud computing because it increased the utilization of servers even further and decreased the importance of client devices like laptops. Strangely enough, the iPhone and smartphones in general were the third negative shock. That’s because they slowed down the growth of the PC market, and PCs are a lot more semiconductor intensive than smartphones in dollar terms. As semiconductors had to go through these three negative demand shocks, the whole industry, the whole supply chain, consolidated. As a result, you have one or two dominant companies in almost each area of semiconductors today.

So what’s next for the chip industry?

Now, we have a positive demand shock in the form of artificial intelligence. Sure, PCs have leveled out, smartphones are slowly additive, the electronic content of cars is growing and so is the internet of things. But AI, because data quantity is so important for quality, is much more semiconductor intensive. For me, a light bulb went off when I read this article in «Wired» about how Google’s engineers started to deploy voice recognition based on AI to Android smartphones. They realized that if each Android phone used Google’s voice search for just three minutes a day, Google would need to build twice as many data centers. What that means is that AI is so incredibly computation intensive that it led Google to develop its own chip called the Tensor Processing Unit or TPU. It’s kind of a graphics processor competitor and it saved Google from building a dozen new data centers.

How will AI translate into demand for semiconductors in general?

AI as a demand driver is just getting going. When humans write software, they understand that we want to limit the amount of computational resources. They write software in very elegant ways to minimize compute and memory. Artificial intelligence is none of that. AI is all about semiconductor brute force. Marc Andreessen wrote this famous op-ed article called «Why Software Is Eating The World». But if you were to rewrite it, you would say AI is eating the world. And, as AI eats the world, software not only becomes more important to every industry, but also more and more of that software is going to be created by artificial intelligence and not humans. That’s why one of my beliefs is that in fifty years, it will be illegal for humans to write software. It will be too important to be trusted to a human being. That means that naturally, the semiconductor intensity of global GDP will rise significantly as AI rises, and it’s happening against the backdrop of a very consolidated industry.

Exhibit A of this ongoing consolidation is Nvidia’s $40 billion Arm deal. What’s your interpretation of the largest semiconductor acquisition in history if approved?

Remarkably, Nvidia is basically paying the same price that SoftBank acquired Arm for four years ago, net of the earnout. The larger take away from this deal is the importance of software: Semiconductor companies themselves are writing a lot of software to enable AI algorithms to run on their chips. Specifically, in the data center you need to take a more holistic ecosystem approach. You’ve had that for Intel’s x86 architecture, but not with Arm. So one axis of the deal is creating a software ecosystem in the data center space for Arm. The other axis is embedding Nvidia’s graphics chips and Tensor cores IP with Arm and pushing that model out to the edge and to places where it makes sense for their chips.

In other words: This mega deal further cements Nvidia’s dominant status as the global leader for graphics processing units or GPUs?

The industry has certainly consolidated, but we will see what happens. Somebody once joked that Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia, had single handedly brought back semiconductor venture capital because of the company’s success in the data center space. Most of the world’s deep learning runs on GPUs, and most of these GPUs are made by Nvidia. But over the last five years, billions of dollars have gone into semiconductor venture capital. In contrast to that, there was almost no venture activity in semiconductors until deep learning really took off. So at the same time as the industry has consolidated, you have a lot of new venture funded, innovative competitors like Cerebras or Mythic coming for different corners of the semiconductor industry and for Nvidia in particular.

Semiconductor stocks like Nvidia have yielded astonishing returns over the last decade. How hard is it to find attractive investment opportunities in the chip sector at these valuations?

There is a lot of dispersion. Nvidia is an expensive stock today, but other areas of the semiconductor industry are quite cheap. GPUs are very important for artificial intelligence, but so is memory. In fact, AI uses six times more memory computing power than software written by human beings. So memory chips are an interesting subsector of semiconductors today, and it’s heavily consolidated. It is a cyclical industry, and it’s slowly becoming less cyclical.

And what about analog chips? With the merger between Analog Devices and Maxim Integrated we’re seeing attempts for further consolidation in this subsector as well.

The analog space is really attractive. It’s an incredible long-term compounder, and the industry is already very consolidated. A lot of people used to make the mistake of thinking that we wouldn’t need analog chips in a digital world. That is not true at all because the world is analog, and taking analog information – light, sound and power – and helping to translate those signals into digital streams of 1s and 0s and manage them is super important. I often say semiconductors are the closest thing to magic in the modern world. Analog is like the black magic because there are only a small number of people in the world today who can design these analog chips. It’s trial and error, it takes a very long time, and it’s almost as much of an art as it is a science.

When it comes to developing leading-edge chips, semiconductor companies have to take bold and costly bets. How do you cope with these risks as an investor?

You watch them very carefully. It’s incredible what’s going on: Another part of magic are these leading-edge process nodes where Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing, Intel, Nvidia, Xilinx, Samsung and Micron are playing. It’s almost like they are developing recipes: Mainly, they are all using the same machines from Lam Research and ASML, and they are putting them together in slightly different ways, using slightly different materials on each layer, or they have slightly different transistors. So they are making these huge ten, twenty billion dollar bets on the right recipe. That’s because you have a big advantage if you get to a node first since you can optimize that node and learn and then apply those learnings for getting to the next node first.

Those giant bets can also go wrong as we just witnessed in the case of Intel.

Intel guessed correctly for the last forty years, and then they guessed wrongly. They probably inserted extreme ultraviolet lithography too late. That resulted in them losing process leadership to Taiwan Semi. This is one of the highest stakes games being played in the world today: In the logic space between Taiwan Semi, Intel and to some extent Samsung. Even in the processor design space Intel, AMD and Nvidia are making giant two, three, four billion-dollar bets on designing a processor, making it work on a manufacturing process. They have to continuously guess right.

For the first time ever, Intel has lost its technological leadership to Taiwan Semi. Is this the end of an era in the semiconductor industry?

The media loves narratives, big turning points and headlines like “The End of an Era”. It’s certainly possible, but Intel is a great and proud company. They have a lot of brilliant engineers, and they are one of the most important national assets for the United States. Today, the leading-edge semiconductor fabrication plants are in America, there are two Intel fabs in Israel, and then there are fabs in South Korea and Taiwan – that’s it! So as an American, I hope that’s not the end of an era for Intel. I would not be as quick to count them out, but for sure they have their work cut out for them. They were always ahead, and now they are behind. That’s a position that is new to them.

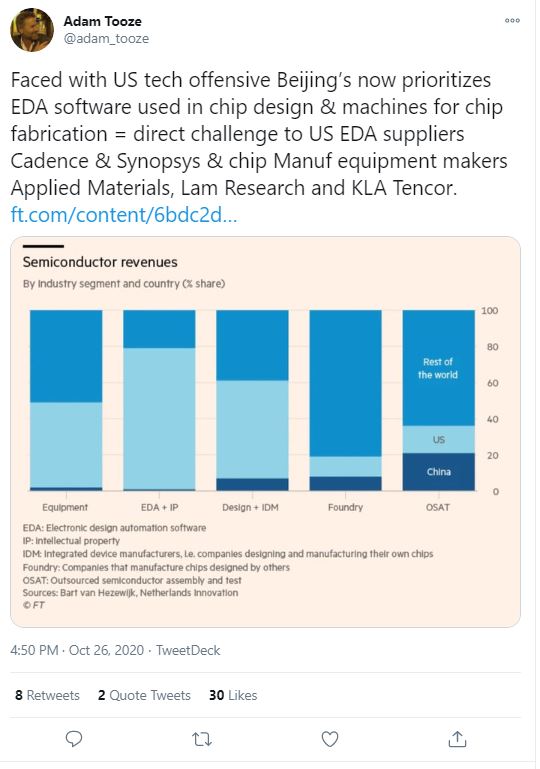

Against that backdrop: What are the implications of the rising tensions between the US and China for semiconductor investors?

If Intel falls further behind and leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing becomes concentrated in Taiwan then Taiwan will become geopolitically important in a way that the Middle East never was. Modern semiconductor manufacturing is at least as important to the economy as oil was in the 1970s. But in the case of oil, at least it was available all over the world albeit at higher prices than in the Middle East. Imagine a world where oil only came from one country, and how important that country would have been for the last hundred years. That is what the world would look like if Intel cannot find its footing and continue to manufacture chips at the leading-edge here in America. Taiwan could become by far the most geopolitically important country in the history of the world.

In accordance with the latest US sanctions, most chip suppliers have suspended dealings with China’s tech giant Huawei. How much of a concern is the tech war when it comes to investments in technology?

It does feel like the US and China are beginning to de-couple somewhat. A lot of companies have been moving manufacturing out of China. But outside of some of the obvious impacts, there is not much to say beyond this: If Huawei isn’t able to sell base stations and phones in much of the world because of US policy and if Huawei is unable to acquire the parts and components it needs to make phones even in China, then there are going to be a lot of winners and losers. But in general, I would just say that the current US industrial policy is very strange.

What do you mean by that?

Essentially, the US is saying to China: We are not going to sell you these semiconductors, but we are going to sell you all the equipment you need to make your own semiconductors. This means that in several years it may be irrelevant. In some ways, the entire global economy rests on a couple of relatively small American, Japanese and European semiconductor capital equipment manufacturers; whether it’s Lam Research, KLA-Tencor, ASML or Tokyo Electron or a couple of American electronic design automation companies with Cadence and Synopsys. Without those companies, you cannot build a semiconductor. In a metaphorical sense, it’s almost like current industrial US policy is saying to China: Airplanes are important. We are not going to sell you airplanes anymore, but we are going to teach you how to make your own airplanes. It’s very strange. If our goal is to limit China’s access to these advanced technologies, the US is doing the exact opposite of what would be logical.

What are you doing differently?

A lot of capital allocators like to ask me about the concept of edge. To me, an edge means a repeatable process that drives alpha. But I don’t believe in edge. I think it’s a fairy tale. The world is too competitive. Going back to AI, investing is where chess was in 1996, when there was an enormous race between human grandmasters and algorithms, and Deep Blue started to beat Garry Kasparov by using brute compute force. Today, that’s why value strategies have stopped working: Value investors used to have an edge. They were very quantitative. Maybe, they had a strong stomach and were willing to buy companies because they were cheap no matter how bad it sounded. But the problem is that anything that can be put in a spreadsheet will no longer generate alpha because it has been arbitraged away by quant investors. There is so much quantitative money chasing those same metrics.

So how do you try to generate alpha for your clients?

To me, all alpha comes from insights. An insight is kind of a differentiated long-term viewpoint about a stock. It’s a differentiated view about the long-term state of the world. Often, these insights are very simple, and a lot of them are right brain: imaginative, being slightly better in seeing the future states of the world. These insights need to be grounded and tested in reality regularly. Also, it pays to boil them down to just a few variables. Like Occam’s razor, the injunction not to make more assumptions than you absolutely need, simple is beautiful when it comes to investing. With electric vehicles for instance, all that matters is efficiency: battery capacity and range to get miles per kWh. You want to focus on the variables that are important instead of the variables that are interesting. So what I spent the most time on is focusing on competitive advantage, because in tech competitive advantage is never static. If you’re not growing your competitive advantage in technology, it is probably shrinking.

https://themarket.ch/interview/semiconductors-are-the-closest-thing-to-magic-in-the-modern-world-ld.2719