Doug Noland 11th April

Sitting at the dinner table, our eleven-year old son inquired: “If a big meteor was about to hit the earth, how much money would the Fed print?” I complimented his sense of humor. Yet it was a sad testament to the historic monetary fiasco that will haunt his generation.

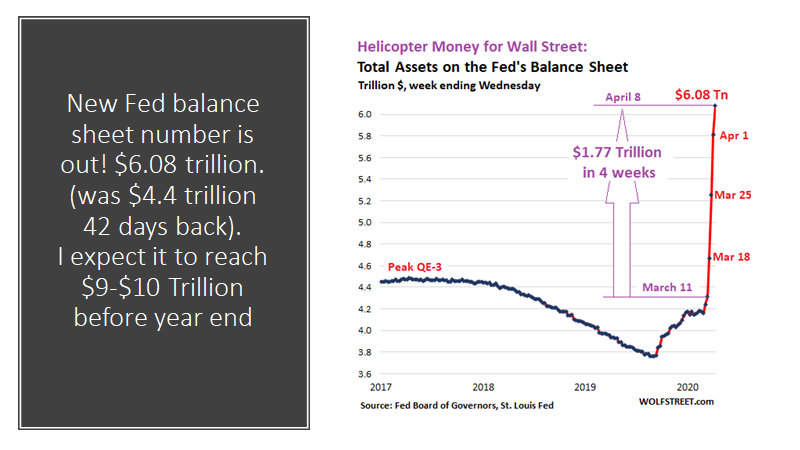

Federal Reserve Assets surpassed $6.0 TN for the first time, having inflated another $272 billion for the week (to $6.083 TN). Fed Assets inflated an astonishing $1.925 TN, or 46%, in only six weeks. Bank of American analysts this week suggested the Fed’s balance sheet could reach $9.0 TN by the end of the year.

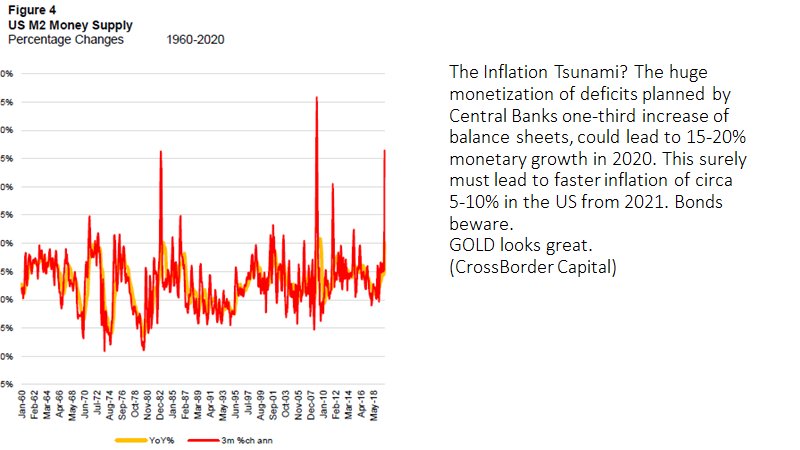

M2 “money supply” surged another $371 billion for the week (ending 3/30) to a record $16.669 TN. M2 expanded an unprecedented $1.136 TN over five weeks (up $2.123 TN, or 14.6%, y-o-y). For some perspective, M2 has expanded more during the past six months than it did during the entire nineties (no slouch of a decade in terms of monetary inflation). Not included in M2, Institutional Money Fund Assets expanded an unparalleled $676 billion in five weeks to a record $2.935 TN. Total Money Fund Assets were up $1.375 TN, or 44%, over the past year to a record $4.473 TN.

There was a sordid process – rather than a specific date – for When Money Died. But it’s dead and buried. There are a few things that should remain sacrosanct. Money is absolutely one of them. Money is special. Sound Money is precious – to be coveted and safeguarded. As a stable and liquid store of value, Money is the bedrock of Capitalism, social cohesion and stable democracy. Society trusts Money – and with that trust comes great responsibility and risk.

Analysis I read some years back on the Gold Standard resonates even more strongly today: Limiting the capacity for inflating its supply, the structure of backing Money with gold worked to promote monetary and economic stability. Yet just as critical were the officials, bankers, businesspeople, market operators and common citizens all adhering to norms and behaviors fundamental to sustaining the monetary regime and resulting Sound Money.

In particular, there was a crucial corrective dynamic that would emerge as a system began to stray from monetary stability. Recognizing that policymakers (fully committed to the regime) would be employing measures to defend stability, market participant behavior in anticipation of policy moves would tend to reinforce stability. For example, if market participants expected officials to respond to credit and speculative excess with tighter policies, markets would exhibit a self-correcting dynamic (reduced lending and risk-taking) prior to the adoption of restrictive policy measures.

I’ve been an avowed naysayer of this global experiment in unfettered global finance for more than 25 years. We have witnessed a unique period in financial history. Never before has the world operated without limits to either the quantity or quality of “money” and Credit. Global finance moved to a massive ledger of electronic debits and credits virtually divorced from real economic wealth – debit and credit entries backed by little; and little holding back the creation of Trillions of additional new “money.” Credit is inherently unstable, and this new “system” early on proved highly destabilizing.

As degraded private Credit turned increasingly unstable, government-based “money” (central bank Credit and government debt) was employed in expanding quantities in repeated attempts to bolster waning market confidence. Witnessing the extent governments were willing to go in post-Bubble reflationary measures, just about 11 years ago I began warning of the unfolding “global government finance Bubble.”

Early on in the Bubble reflation, I warned that QE would distort markets and fuel asset price Bubbles. I would repeatedly get similar pushback: “Doug, how is it possible for QE to be distorting the markets when these Fed liabilities are just sitting (inertly) within the banking system? How can Federal Reserve “money” be in two places at once?”.

Recent weeks have offered a rather straightforward example of the mechanics. When the Fed creates new liabilities (Rothbard’s “money out of thin air”) to purchase Treasuries (along with MBS, corporate bonds, bond ETFs, municipal debt and, going forward, junk bonds and “main street” loans), these “immediately available funds” flow into the banking system where they are exchanged for bank deposits (new bank deposit liabilities matched against an asset “reserves at the Fed”). Some of these deposits will flow immediately into the money markets, especially to institutional money funds after Federal Reserve market purchases from the institutional investor community. It is certainly no coincidence that M2 plus Institutional Money funds have increased $1.81 TN in five weeks as Fed Credit inflated $1.82 TN.

Questions following Chairman Powell’s April 8, 2020, speech, “COVID-19 and the Economy”:

David Wessel, Director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institute: “The Fed has cut interest rates to zero – you’ve bought hundreds of billions worth of Treasury bonds and mortgages; you’ve launched an alphabet soup of lending programs – including some new ones today for state and local governments and mid-sized businesses – that you say could lend up to $2.3 TN dollars. Is there any limit to how much money the Fed can create – how much it can lend – without having some unwelcomed side effects – like inflation or asset price Bubbles?

Powell: “These programs that we’re using – under the law we do these…, as I mentioned in my remarks, with the consent of the Treasury Secretary and with fiscal backing from the Congress through Treasury, and we’re doing it to provide Credit to households, businesses, state and local governments, as we are directed by the Congress. And we’re using that fiscal backstop to absorb any losses that we have. And what we’ve been doing is looking for places that are very important to the real economy – things that really affect people’s lives and economic output – and where Credit to those parts of the economy has broken down… That’s essentially what we’re doing. And we can keep doing that as long as those needs arise. Our ability to do that is, really, limited by the law. We have to find unusual and exigent circumstances. The Treasury Secretary has to agree. And we are using this fiscal backdrop. But there are really no limits to how much we can do other than it must meet the test under the law as amended by Dodd Frank.”

Wessel: “Isn’t there a risk that with all of this money coming out of Congress – the money and lending – that we’ll end up with something that we don’t like, as in more inflation than we’d like or asset Bubbles?”

Powell: “Inflation has been an interesting phenomenon. Back 12 years ago, when the financial crisis was getting going and the Fed was doing quantitative easing, many people feared that the increases in the money supply, as a result of quantitative easing asset purchases, would result in high inflation. Not only did it not happen, the challenge has become that inflation has been below our target. So that is – globally the challenge has been inflation below target. Honestly, it is not a first-order concern for us today that too high inflation might be coming our way in the near-term. Far from it. These are programs that we’re developing at a high rate of speed. We don’t have the luxury of taking our time the way we usually do. We’re trying to get help quickly to the economy as it’s needed. I worry that in hindsight you will see that we could have done things differently. One thing I don’t worry about is inflation right now.”

The Fed Chair ducked the “asset Bubble” question – twice. AP: “Wall Street Caps Best Week Since 1974 on Fed Stunner” – and in only four trading sessions. Bloomberg: “U.S. Junk Bonds Rally Most in Two Decades with Fed Now a Buyer.”

There are important reasons why the Federal Reserve (and central bank generally) traditionally limited purchases to T-bills. Any central bank purchase outside of money-like instruments will impact its price along with market perception of safety. And the farther a central bank goes out the risk spectrum the greater the distortion. A popular high-yield ETF (HYG) surged 12% this week with the Fed announcing it would begin purchasing some junk bonds, a glaring example of a distorted market diverging from underlying fundamentals. And the greater the divergence, the more destabilizing the eventual collapse back to reality.

In stark contrast to gold standard dynamics, contemporary markets move only further away from stability in anticipation of only more vigorous policy inflationary measures (unsound “money” promoting the opposite of self-correcting market dynamics).

Dr. Bernanke argues that had the Federal Reserve recapitalized the banking system early in the downturn, the U.S. would have avoided the Great Depression. I have posited the key issue was not replacing some finite quantity of depleted bank capital – but rather a much greater amount of ongoing system-wide Credit required to sustain maladjusted financial and economic structures following the historic “Roaring Twenties” Credit inflation.

Non-Financial Debt (NFD) expanded $2.485 TN in 2019. This was the strongest Credit growth since 2007’s record $2.521 TN, and 42% above average annual NFD growth over the previous decade. Asset markets (stocks, bonds, corporate Credit, residential and commercial real estate, etc.) have never been so inflated. The Fed, the Trump administration and Congress are determined to immediately reflate the U.S. economy and asset markets back to where they believe are sound and sustainable levels.

This will prove a Herculean endeavor. The Fed’s aggressive liquidity measures and resulting market recovery have created a precarious dynamic whereby badly distorted and inflated markets will require persistent liquidity support. Never have such incredible “money” creation operations been used only weeks from record stock prices and economic boom conditions. I believe to sustain recovery of such an economic structure will require unending massive fiscal deficits. Regrettably, there’s no end in sight to today’s reckless monetary inflation – consequences of this Scourge of Inflationism to unfold over months, years and decades.

I worry greatly about exacerbating already threatening inequality (a consequence of When Money Died). One of the cruelest aspects COVID-19 is how hard it is hitting our minority and poorer communities. The Fed will create Trillions and Washington will spend Trillions more, and large segments of our population will undoubtedly have issues with how all this “money” was allocated. The Fed knows better than to be in the allocation game – Credit, “money” or otherwise. And I doubt their new “Main Street” program will absolve the Fed of responsibility in the eyes of the general population. The Fed now “owns” these dreadfully unstable markets – placing its institutional credibility – and trust in “money” – in peril.

When Money Died globally…

April 9 – Reuters (Judy Hua and Kevin Yao): “New bank lending in China rose sharply to 2.85 trillion yuan ($405bn) in March, with total social financing hitting a record, as the central bank pumped in more liquidity and cut funding costs to support the coronavirus-ravaged economy… New loans in March far exceeded market expectations of 1.8 trillion yuan and were three times more than February’s 905.7 billion yuan. That nudged bank lending in the first quarter to a record 7.1 trillion yuan, beating a previous peak of 5.81 trillion yuan in the first quarter of 2019… Household loans, mostly mortgages, rebounded sharply to 989.1 billion yuan in March from a net decline of 413.3 billion yuan in February… Corporate loans almost doubled to 2.05 trillion yuan from 1.13 trillion yuan the previous month. Growth of outstanding total social financing (TSF), a broad measure of credit and liquidity in the economy, quickened to 11.5% in March from a year earlier and from 10.7% in February.”

I’m left to ponder how the Chinese renminbi would trade in this environment against a sound U.S. dollar. First quarter Chinese Bank Loans of $1.008 TN were up 22% from Q1 2019 – a truly incredible expansion in the face of collapsing economic activity. Total Q1 Aggregate Financing was up 29% y-o-y to an amazing $1.574 TN. In a number difficult to fathom, Chinese M2 “money supply” surged $2.720 TN, or 10.1%, over the past year to $29.382 TN.

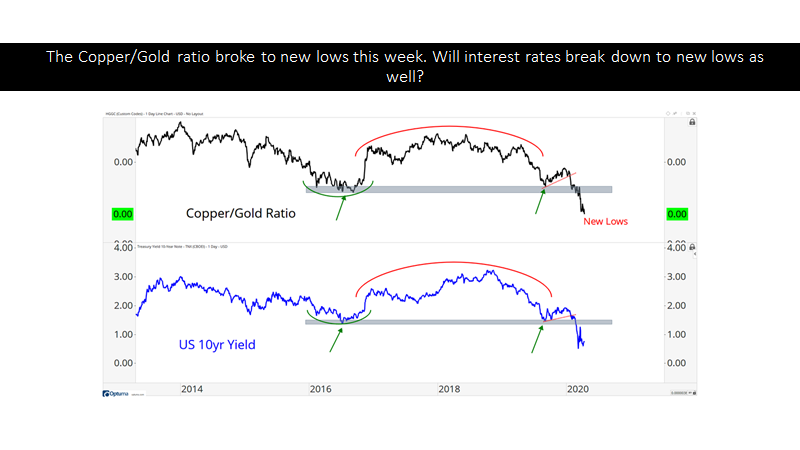

Fed and PBOC “money” notwithstanding, global financial conditions have tightened. Borrowers, stung by job losses, collapsing demand and risks unforeseen, will add debt more cautiously going forward. Lenders, shocked by the prospect of massive defaults across business lines, will extend Credit more cautiously. Unappreciated risks associated with myriad sophisticated financial structures have been exposed. Moreover, confidence in central banks’ capabilities has been shaken. Even in the face of massive central bank liquidity injections and market support, I still believe the risk vs. reward calculus for global leveraged speculation has been fundamentally altered. If this is correct, the Fed’s balance sheet will be getting a whole lot bigger as it continues to struggle mightily to sustain unsustainable market Bubbles.

I often highlight how the “Terminal Phase” of Credit Bubble excess experiences an exponential rise in systemic risk, with ever-expanding quantities of increasingly risky Credit. I fear we’ve commenced the “Terminal Phase” of monetary inflation, with systemic risk now rising parabolically. When Money Died.

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2020/04/weekly-commentary-when-money-died.html