Making sense out of Chaos

The financial markets seem disoriented. The mood on Wall Street changes daily, the S&P 500 keeps trading sideways. Rising counts of Covid-infections in Europe and in the US as well as political uncertainty keep investors on their toes.

Jim Bianco advises caution. When we last spoke to the internationally renowned macro strategist from Chicago in mid-March, panic was in the air. There were even fears that markets would have to close. «Luckily we didn’t get that far,» says Bianco. «But it was a lot closer than most people realize.»

Today, things seem calmer. Nevertheless, Mr. Bianco sees no reason for complacency. According to his view, there are obvious signs of a full-blown retail mania in the stock market. He also warns that the Federal Reserve could lose control over the bond market if inflation picks up next year.

In this in-depth interview with The Market/NZZ, the outspoken investment specialist explains why he thinks the risk of renewed lockdown measures is significant, what kind of market reaction investors should expect with the respect to the US elections and how to position your portfolio for the current environment.

Mr. Bianco, trading has become quite choppy as investors cope with an uncertain outlook for the economy and political risk in Washington. What’s your take on the financial markets?

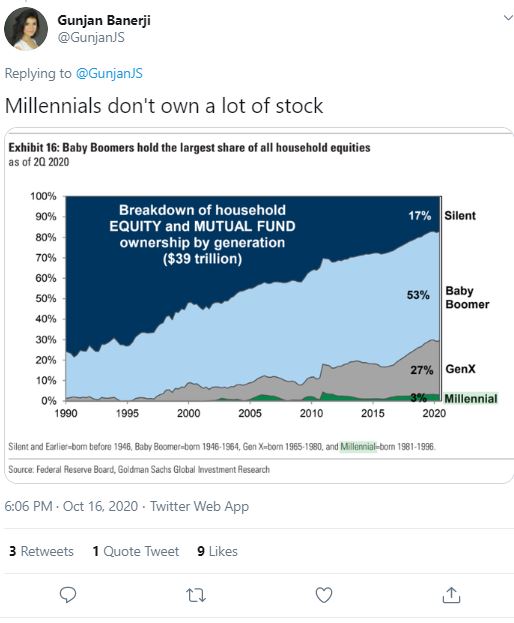

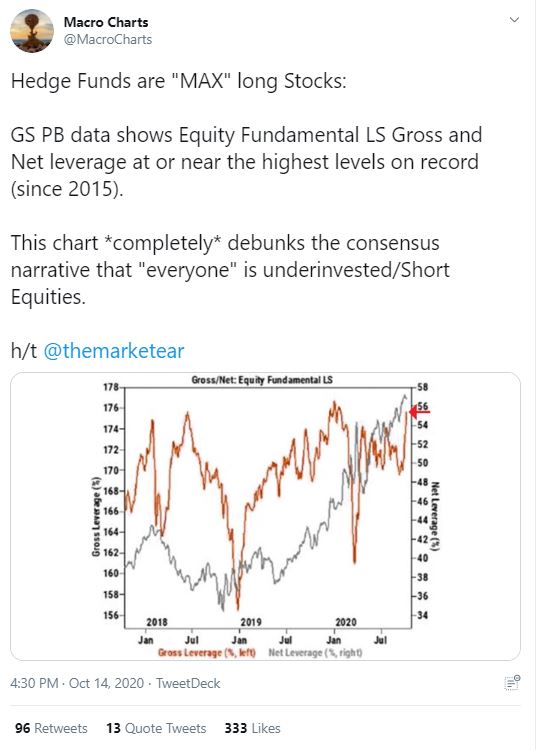

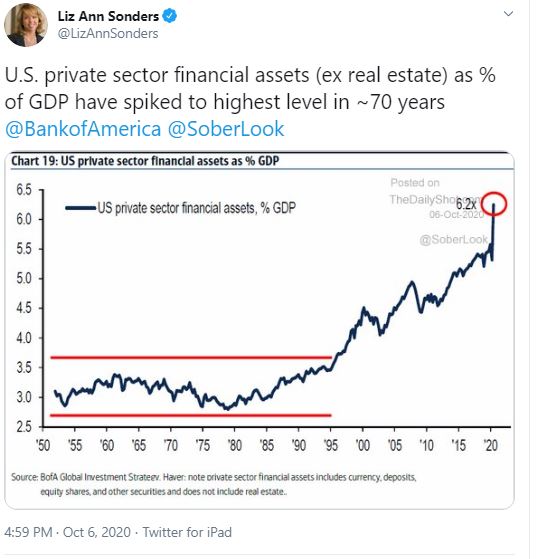

The stock market has a two-fold issue. On one hand, retail investors are dominating the market. There’s no doubt that we’re seeing a full-blown mania coming from the single-stock options market. What’s more, valuations are at or near the 2000 peaks. Whether you’re looking at forward P/E ratios, market capitalization to GDP or other metrics. If you take out the FANG stocks, valuations are even higher than in 2000. This all sounds really bearish: You’ve got mania, and you’ve got stretched valuations.

What’s the second aspect of this two-fold issue?

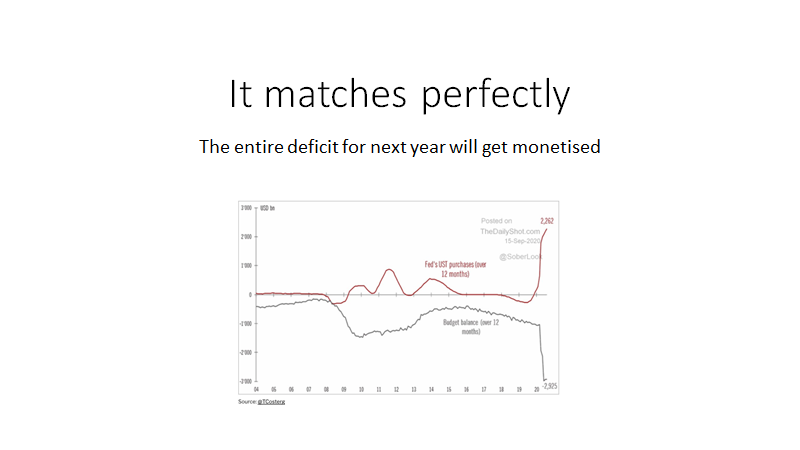

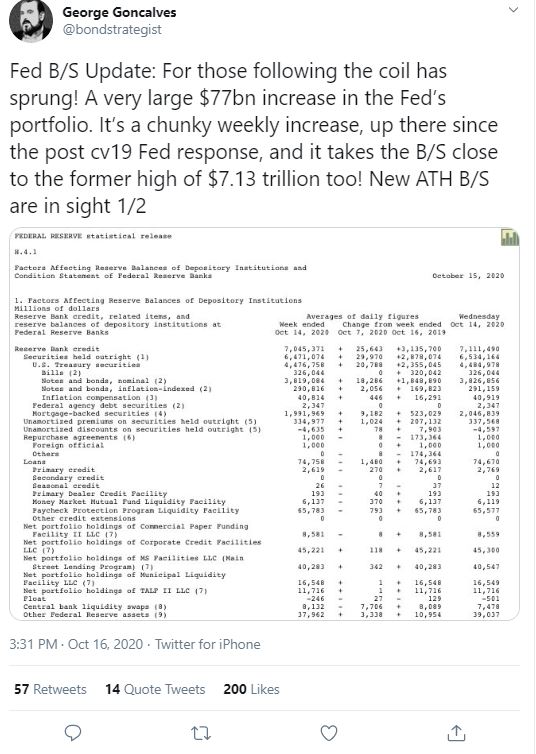

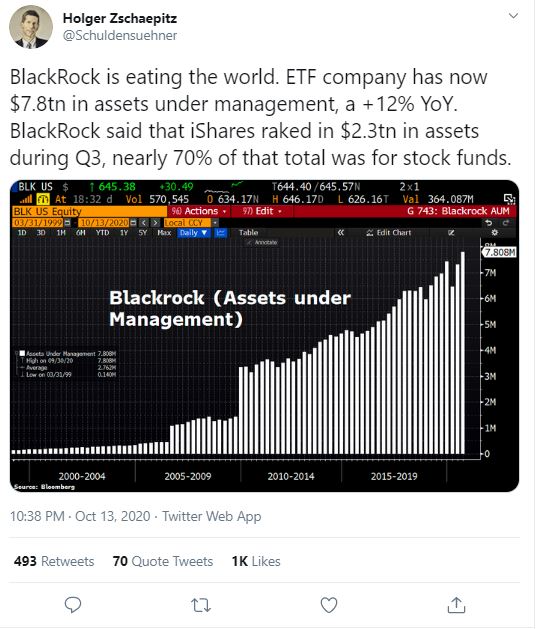

On the other side of the equation you have the Federal Reserve, and they have kitchen sinks which they can throw at the market. At least, that’s the feeling. This is more than traditional monetary policy. The Fed was always involved in the markets, but never to this degree. They maintain facilities to buy corporate bonds, ETFs, municipal securities, PPP loans and other things – and that’s in addition to quantitative easing on levels no one would have ever imagined.

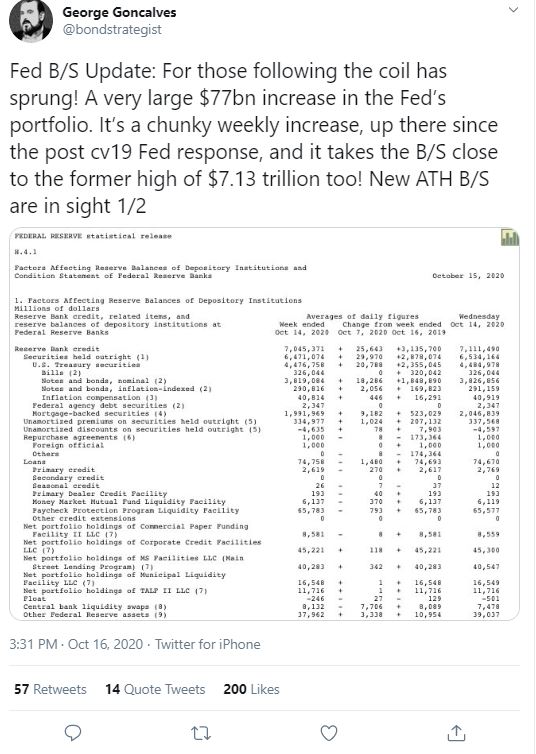

Yet, over the past few months the Fed’s balance sheet basically stopped growing.

That’s correct, but today these facilities are in place, and the Fed can start buying ETFs again in ten minutes. When they made their announcements in March, it took them two months to put these facilities together. Now, they can turn it back on at any point. That’s the other side of the equation, and it was tempering the recent decline in stocks.

What’s going to happen next?

We had exactly a 10% correction on the S&P 500 on an intraday basis. I think that’s about the extent of it for now. Until a new narrative develops, we are probably going to trade sideways. It’s very possible that this new narrative can be negative, and there are two potential negatives hanging out there: The presidential election and a second Covid wave.

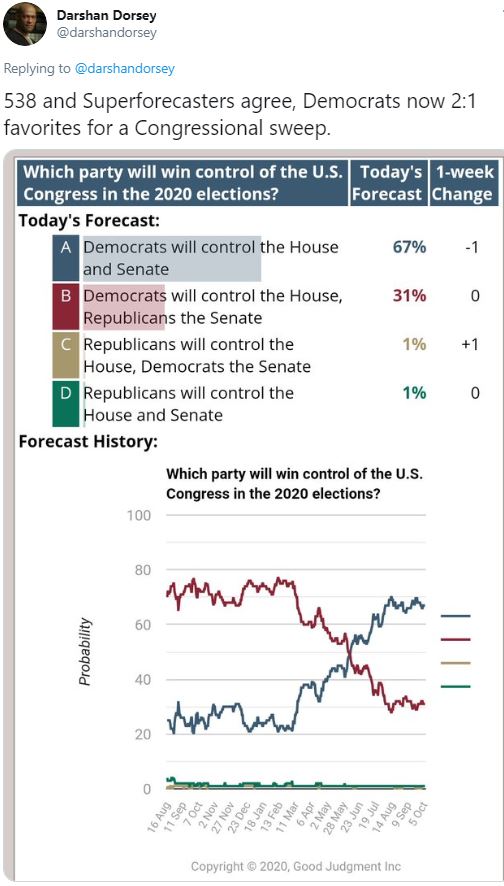

Let’s start with the election. You’ve recently talked about the race for the White House in your new Podcast, Talking Data.

I’m looking at two things. Number one, the gut reaction is that everything you think you should do is already in the market. But I don’t think it is. According to poll analyzers like Nate Silver, Charlie Cook or The Economist magazine, there is like a 85% chance Joe Biden is going to win. They’re basically announcing it’s over; we’re just quibbling how big Biden’s victory is going to be. But if you look at the betting markets, Donald Trump has almost a 40% chance to win. Also, there is a London based pollster called Survation. They recently polled 91 investment managers and 60% of them said Biden is going to win. That means investors line up with the betting markets, not with the polls. So if the polls are right, there is going to be a negative Biden discount in the market to come as Trump’s betting odds fall. On the other hand, if betting markets are right and the polls eventually start to tighten, we’re not going to see a big move like a pro-Trump rally because the market is already there.

And what’s number two?

Here’s a rational argument for last week’s ridiculous debate: About 95% of the country – and this is no joke – already knows who they are going to vote for. Whatever people thought going into the debate, is what they think after the debate. That said, only 60% of the public votes. So this election is going to be determined by turnout. Biden and Trump were not on stage to convince somebody to vote for them. They were trying to get people to actually do it.

Shortly thereafter, we learn about the Covid-outbreak in the White House and the President needs to get treated in the hospital. What do you think is going to happen on election night after all that drama?

My biggest concern is a «red mirage» or a «blue shift»: The mail-in balloting is expected largely to be Democrat, whereas in-person voting at polling stations is expected to largely skew Republican. Because of that, it’s very possible that on election night, Trump has enough votes to win the election, and comes out to declare victory. But then, as we start counting the mail-in ballots over the following couple of weeks, one by one states flip from Republican to Democrat, and by Thanksgiving, the election is gone the other way. I’m not suggesting any impropriety or fraud, but if that’s the scenario that plays out, I have a feeling that a lot of people won’t accept the outcome. They’ll think it was rigged and that the election was illegitimate.

How would the markets react to that?

This is not 2000 when the contested election came completely out of the blue and lasted 36 days. During that period of the time, the S&P 500 declined 13%. I think we won’t know on election night who won, and certifying the election results will take several days. If it doesn’t result in a legitimacy question, it’s largely a non-event for the markets. But if it takes a longer period of time, and it results in a question of legitimacy, that’s a big negative for the market. Even worse: If it gets really acrimonious with lawyers and everything else, and we get into January 20th and we don’t know who won, it’s a disaster scenario for the markets.

How does Covid play into this? Leading up to the first wave, you’ve been one of the very few market observers who saw the pandemic coming and warned early about the dire consequences for the economy.

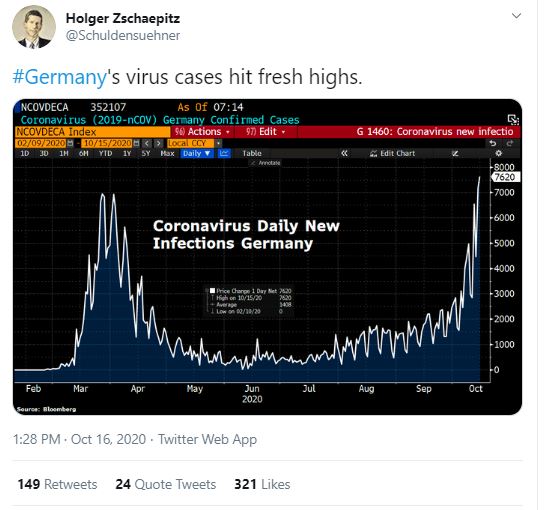

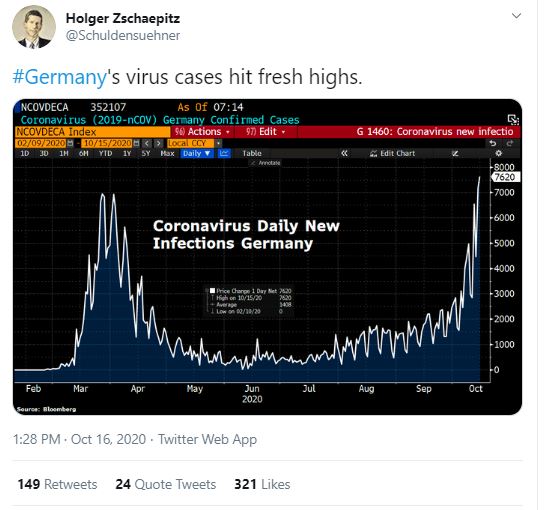

Right now, Europe has the highest case counts. The virus is spreading especially in the UK, in Spain and in France. True, this time the case counts are resulting in less hospitalizations and less deaths. That’s possibly because we have better treatments and a better understanding of the virus. It’s also possible that this mutation is more contagious but less lethal. But death and hospitalization charts don’t really matter.

Why?

People’s mobility – their economic activity – and government policy are going to be determined on the case count. If cases go up, older people won’t go out and interact with other people. Also, no politician is going to say: «Cases are booming, but no one is getting really sick, so we won’t change our policies and roll back some of the shutdown.» Let me be clear: We won’t go back to April, but there will be policy measures to slow down the spread. You are starting to see that in the UK, for instance. There will be some roll back pulling down economic activity.

What does this mean for the US economy?

The question is if Europe and the Northern Plains – states like Wisconsin, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and Colorado – are leading indicators. The situation is especially bad in Wisconsin, where they are openly talking about hospitals getting overrun. In addition to that, Wisconsin is a swing state, and if it winds up having a full blown Covid crisis by November 3rd, that could play into the election. At this point, I bet that you are going to see some kind of second Covid wave in the US, and I suspect we will get some roll back of the lockdowns.

How would that impact the financial markets?

As mentioned, by most measures the market is probably overvalued. The hope is that despite the market being a little bit ahead of itself, the economy will eventually speed up and justify these valuation levels. But if we get a second Covid wave, even if it’s not as lethal as the first one, it will retard growth enough that the economy will not meet those valuation levels.

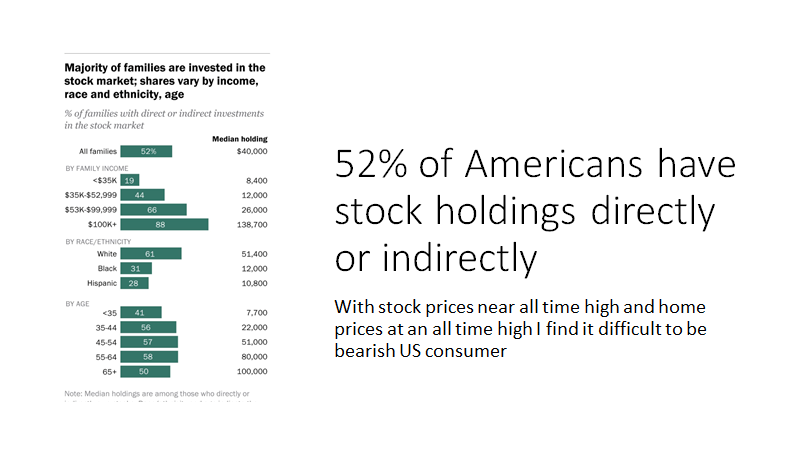

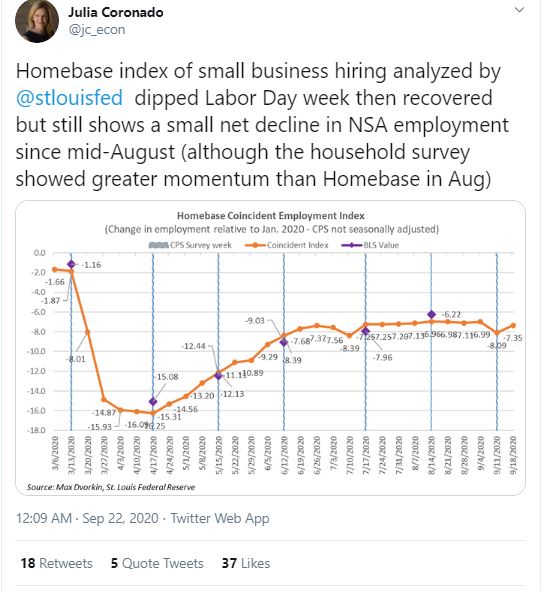

There are already signs that the recovery is slowing. What’s the current state of the US economy?

According to high frequency data such as initial claims, restaurant bookings and mobility indicators, the economy bottomed in late March/early April, just like the stock market did. But then, around mid-July to early August, the recovery stalled. It’s not reversing, but it stopped getting better. We know that real GDP growth in the second quarter was the worst ever recorded at -31.4%. And we know that Q3 should be the best ever recovered with estimates near +28%. So we’ve gotten back around two thirds of the loss during the shot down.

What should be expected next?

Now, the recovery has stalled. Back in June, the consensus was expecting a massive growth quarter for Q4 of more than 11%. This forecast has been falling hard and is now just 3.6%. While 3.6% is a decent quarter, there are no assurances this forecast is done falling. The quarter is only seven days old and some economists are openly talking about Q4 being another negative growth quarter.

But isn’t there also a chance that the economy could pick up steam again.

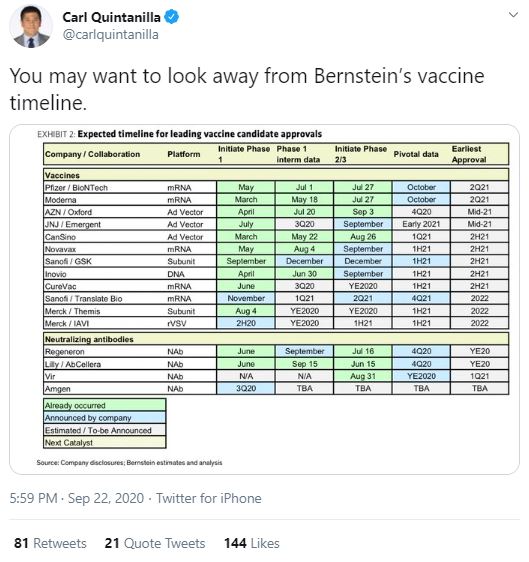

The medical bailout is still hanging out there. By that I mean a vaccine or a treatment. Today, there are several vaccines in Phase III trials. Thanks to Operation Warp Speed, the US government has already awarded massive contracts to start producing doses of all these vaccines now, and the military is putting together ways to administer them ASAP. So as soon as a vaccine is approved, they already have hundreds of millions of doses ready. But according to leading companies like Moderna or Pfizer a vaccine will not be ready until spring or summer 2021. That means a second Covid wave can really slow down the economy.

That’s why the financial markets are laser focused on a new stimulus bill. How likely is it that Republicans and Democrats will agree to a deal?

I thought a deal would come already in August. If you had a PPP loan or any of the bailout money from the earlier stimulus packages, part of the deal was that you will get your PPP loan forgiven or get a better deal on your bailout money if you don’t lay off anybody until September 30th. But now, we have airlines and other companies like Disney furloughing tens of thousands of people. Therefore, I expect a renewed push by both, the Democrats and the US administration, to get a deal. Both sides are afraid to be blamed for a giant jump of unemployment. So I’m operating under the assumption that we are going to get see at least some kind of partial deal.

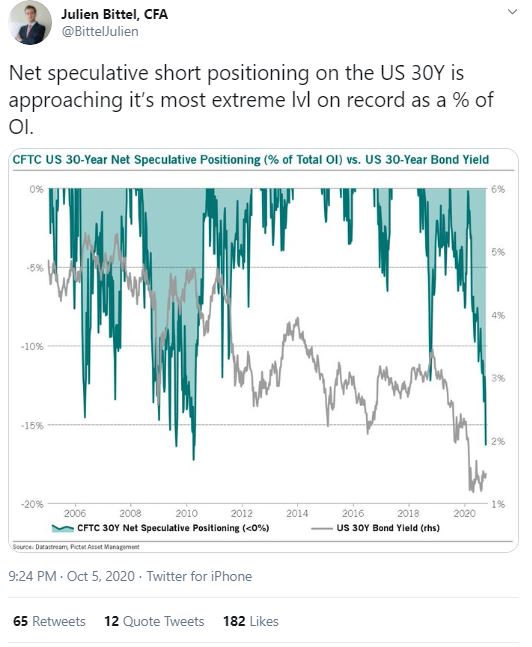

In stark contrast to stocks, the bond market has hardly been moving until recently. It this bond market now finally waking up?

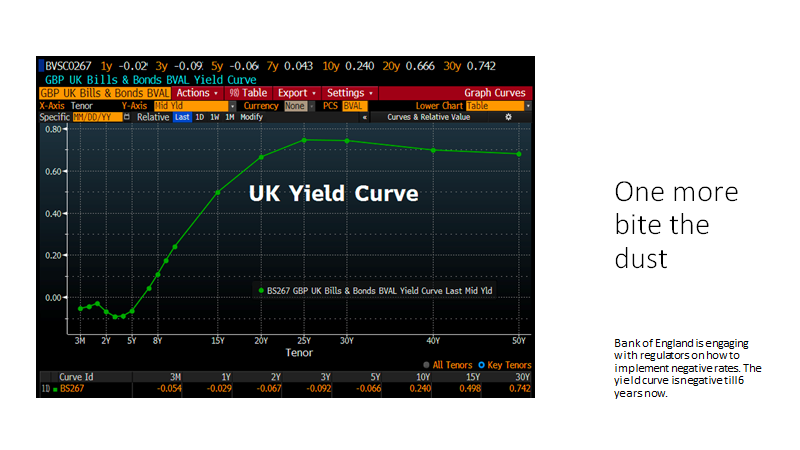

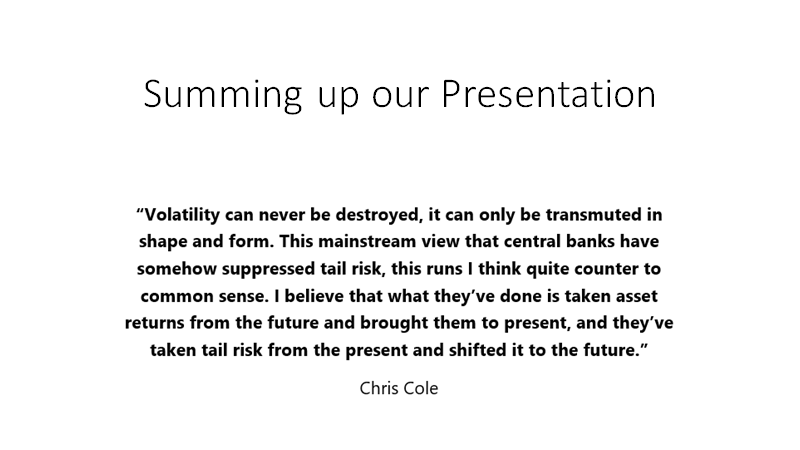

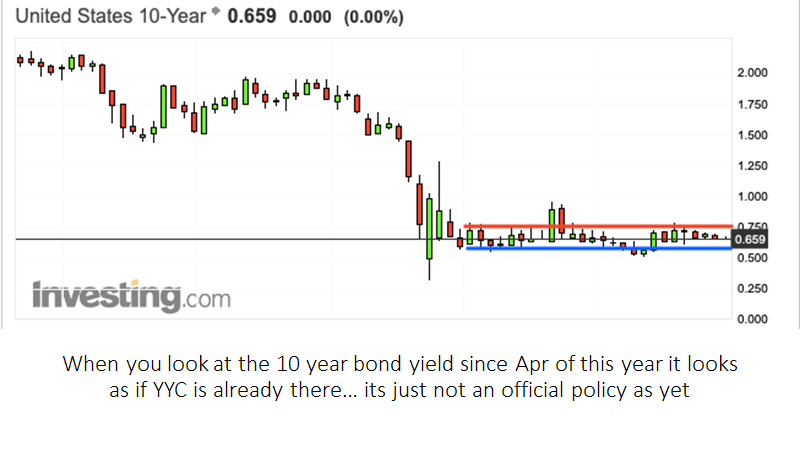

The bond market has seen one of its quietest periods in history. The MOVE index, the VIX index for the bond market, hit an all-time low last week. A main reason for that is heavy central bank intervention. Since March 13th, when the Fed ramped up QE, it has purchased $3.3 trillion of bonds, and it’s still doing 10 or 11 billion dollars a day. That has a big dampening effect. Another reason is yield curve control. Basically, that’s just price fixing where the Fed announces it will buy or sell as much bonds as it needs in order to keep interest rates at its target level. Well, with all that bond buying going on today, we virtually have already yield curve control, and it’s killing volatility. It’s killing interest in the bond market, and it is keeping rates low and stable.

The Fed’s strategy seems to be working for now. But what about the unintended consequences of these war like policy measures?

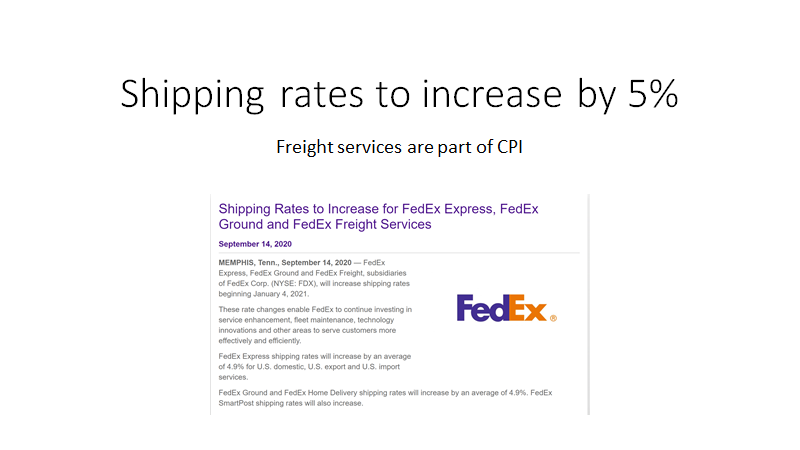

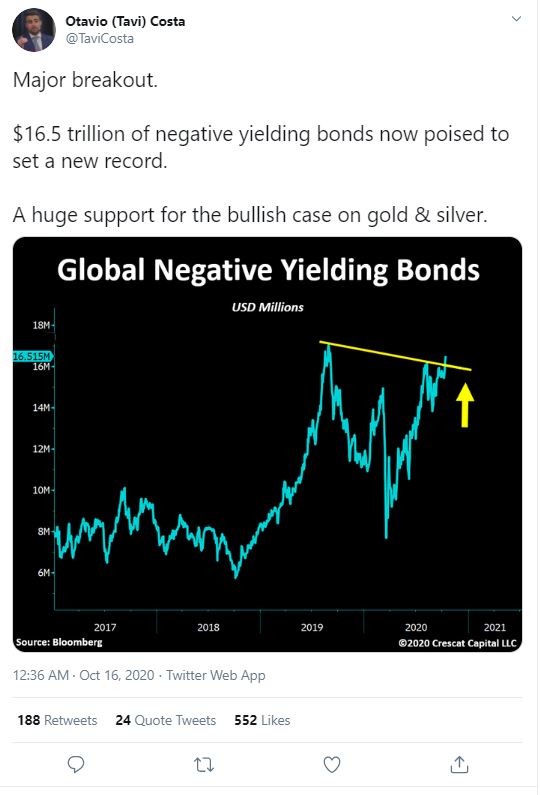

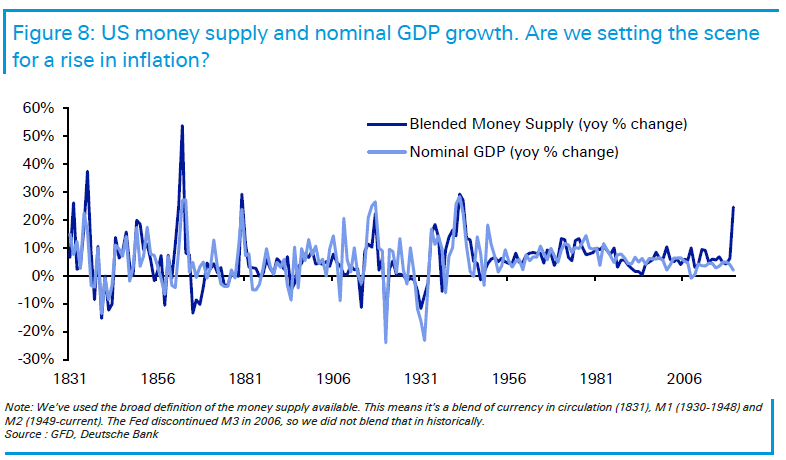

The game changer will be inflation. The recovery has stalled, so we are producing less stuff. On the demand side, 9 million people have lost their job since the beginning of the pandemic. That’s why we’re artificially stimulating demand with government intervention. Less supply and more demand equal higher prices, and it’s likely that we are going to see a rise in inflation in the next year when the year-over-year comparisons get through the worst of the pandemic. Today, the core PCE – the Fed’s favorite metric – is around 1.25%. For me, inflation would mean a reading of 2.5 or 2.75%. Essentially, the last time the core PCE was at that level was 1993. If we get that, it’s going to be a real problem.

Then again, a rise in inflation is exactly what the Fed wants.

One of the things that’s larger than central banks is the market itself. The Fed wants to let inflation run because they want unemployment to go down. They’re sincere about that, but when the bond market decides that inflation is a problem, the Fed is going to be forced to react. Think about it this way: The Fed is like a post, and the market is a horse tied to that post. If you tie a horse to a post, it just sits there, and it doesn’t do anything for a while. But a horse is a 1500-pound animal, and if inflation spooks the horse, it will tear the post right out of the ground and run away. So yes, the central banks can control the bond market for some time. But when you spook it, it will rip that post right out of the ground and go, no matter what the central banks try to do to tamp down rates. My bet is that’s what’s going to happen in the second half of 2021.

What does this mean for risk assets like stocks?

I don’t think we have much more in the cards for the S&P 500 because I see too many problems: Stretched valuations, the election and a second Covid-wave. For now, they’re offset by the Fed. But I still contend that the 39-year bull market in bonds has ended on March 9th at 33 basis points on the ten-year treasury note. The next big move is going to be higher in rates. If I’m right, higher rates are going to be a big problem for all risk markets: stocks, credit and the whole nine yards.

How should investors position themselves against this background?

If I’m wrong and the yield on the ten-year note goes down to 33 basis points again, or we make a new low, this would mean we have another bad economic contraction, probably another recession. So what’s the best scenario for risk markets? The bond market stays asleep. If it wakes up in either direction, it’s going to be problematic. Higher rates mean inflation which is a problem for the bond market and filters into everything else. If rates plunge on the other hand, that’s an economic contraction and a problem for earnings.

What’s a good way to prepare yourself for more volatile times ahead?

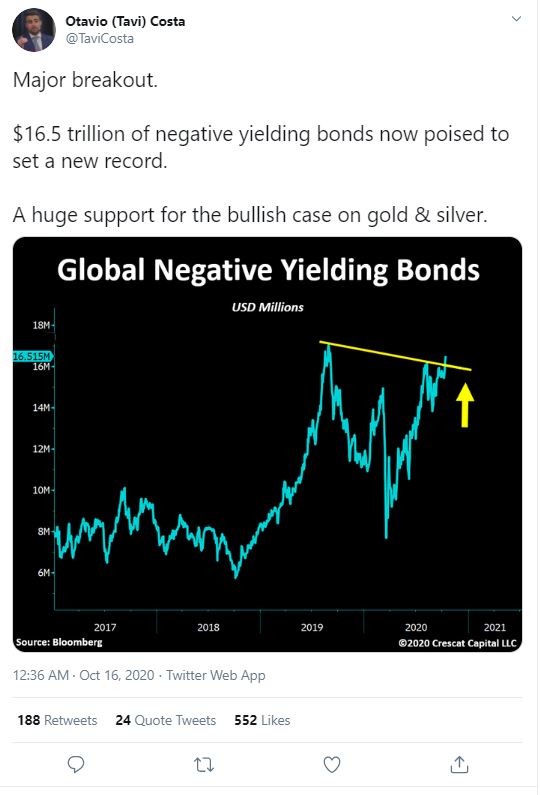

The big thing I would emphasize is that the traditional stock-bond relationship is changing. That’s a fancy way of saying a 60/40 portfolio is not going to work as well as people think. You don’t have a natural hedge anymore when you put 60% in equities and 40% in bonds. At this point, the stock market really has to stumble in a big way, and you are not going to get as much help from the bond market. That’s why portfolio construction between bonds and stocks needs to be rethought. Gold can be a part of the solution, but gold is still a very uncorrelated asset. The negatively correlated asset for stocks used to be bonds, and there really isn’t any other one.

What else besides gold do you want to own in such an environment?

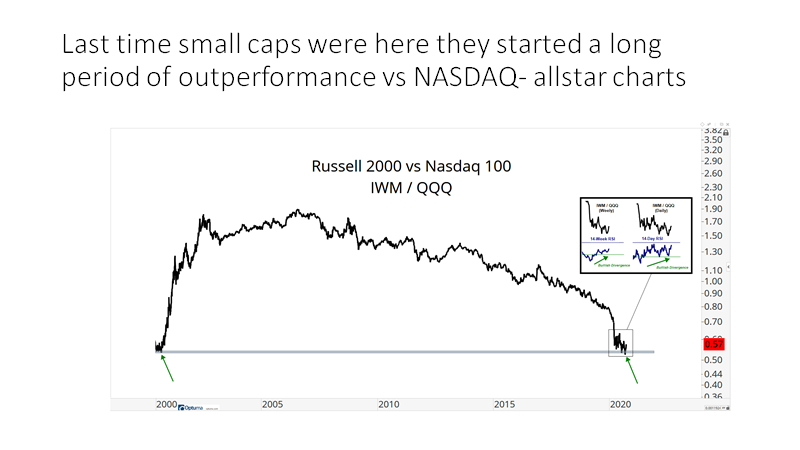

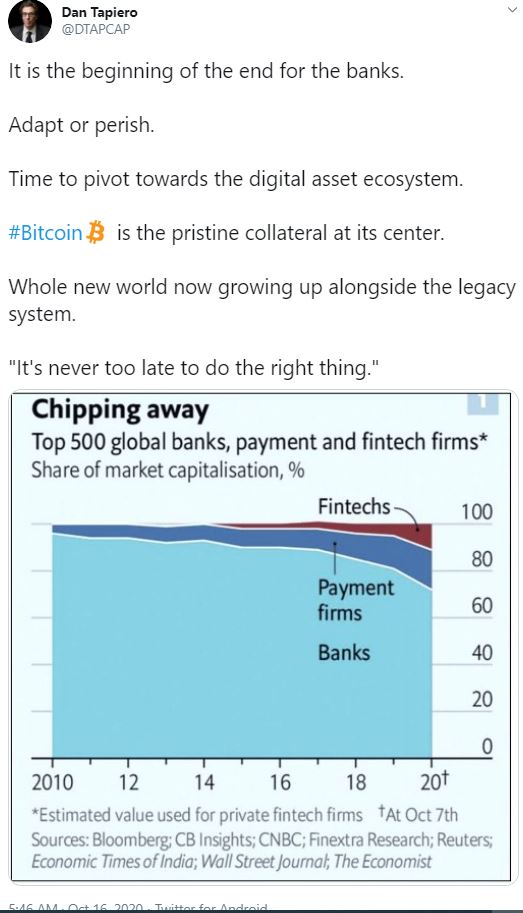

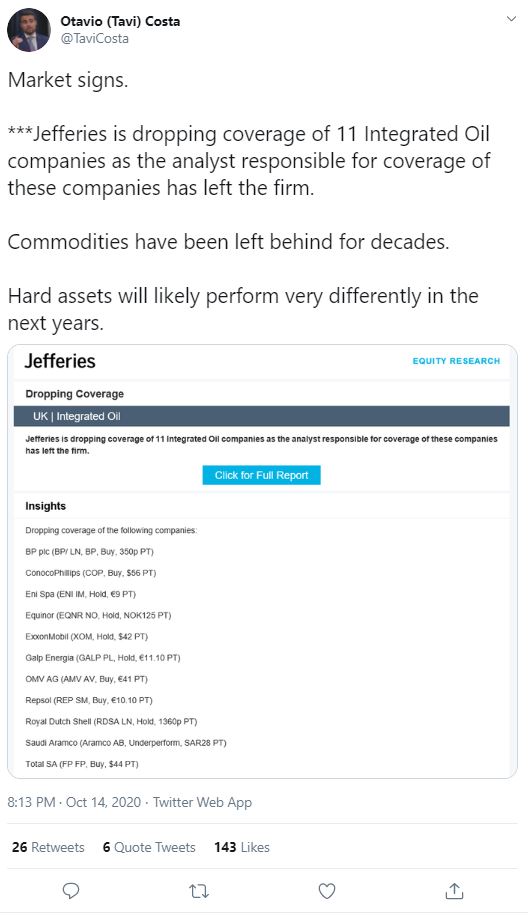

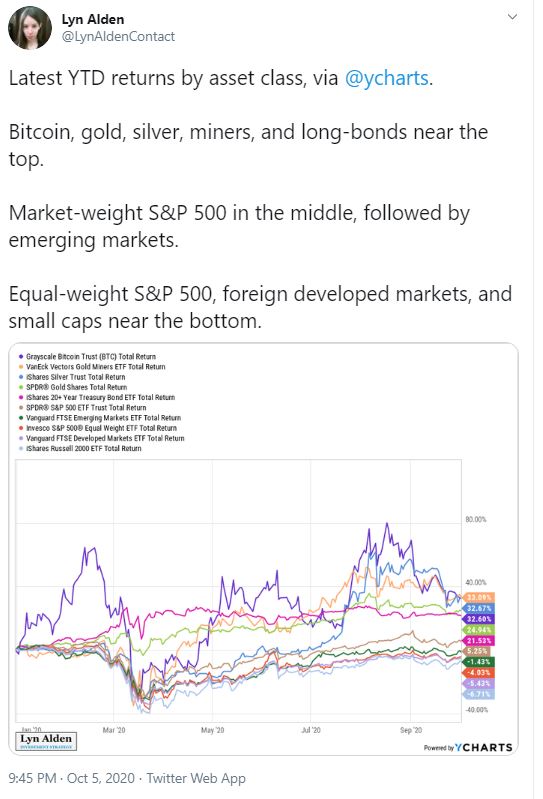

One of the interesting things happening in the stock market this year is the unprecedented dispersion of returns. On a year-to-date basis, the technology information sector is up close to 30%, and the energy sector is down 50%. That is a 80% swing from the best to the worst sector. Also, financials are down 20%. These are unbelievable dispersions. If you get everything right, but you own a little bit too much energy, you have a really bad year. In contrast, if you have everything wrong, but you wound up with a lot of FANG stocks, you are having a really good year. So sector positioning is going to continue to be a big play.

So what’s the best strategy when it comes to sector positioning?

I am not a fan of the financial sector, but I’m interested in the energy sector because it has been so eviscerated. Although, it’s a very speculative play. Also, I do like consumer staples and healthcare. Count me as one of those thinking that we’ve completely played the tech sector out. Sure, we’re talking on Zoom for this interview. But the fact that the entire US airline sector has an $80 billion market cap, and Zoom has a $140 billion market cap tells me that Zoom has likely done its thing. At this stage, everybody knows what WFH means. I’m not extraordinarily bearish on technology stocks, and I don’t think they are a short. But they have kind of run their course at this level.

How about investments outside of the US?

I prefer the US over Europe right now. With the second Covid wave, Europe is going to really struggle until it looks like the economy is going to return to normal. If we do get a vaccine, and people want to take it, a good play would be emerging markets. Once we do get back to normal, they will benefit more than everybody else. They are producers of stuff for the developed world. Today, the developed world is hiding in their house. But as soon as the developed world goes back to buying stuff, emerging countries will prosper. It’s a little bit early, but next year I will be looking at emerging market investments as well. What’s more, if you want to buy inflation protected securities, things like TIPS will play, too.

Link : https://themarket.ch/interview/inflation-will-be-a-game-changer-ld.2824

Simon Black Bahia Beach, Puerto Rico

Last Tuesday night, around 10:30pm the Google search term, “How to apply for Canadian citizenship,” spiked.

Other popular searches that night included “how to move to Canada” or simply, “move to Canada.”

This was in response to two men in their 70s childishly bickering at each other for an hour and a half, televised live across the world.

For people in the United States, Canada always seems to be the first place that comes to mind whenever they think about leaving.

It seems every time there’s a controversial election, for example, a bunch of celebrities always threatens to move to Canada. (In 2016, the list included Snoop Dogg, Barbara Streisand, actor Bryan Cranston, and comedian Chelsea Handler… though none of them actually moved.)

It’s an obvious first choice given the similarities between the two countries.

But if you’re serious about making a move– or at least identifying a place you -might- consider moving to– before the chaos escalate, taxes go through the roof, or the public schools convince your child to identify as a seedless watermelon. . . then take a look at the menu.

The world is a big place, and there are dozens of countries around the world to choose that offer the widest variety of climate, culture, lifestyle, nature, business/investment opportunities you could imagine.

If you do like the cooler climate, with four distinct seasons, maybe look into Estonia or Georgia– both offer certain remote workers residency for a year. You could try it out, and see if you are serious about leaving your home country behind.

If you want to be in a similar time zone as North America, you could go south to Panama or Barbados, both of which have straightforward residency processes or temporary work permit options.

If Europe is more intriguing, Spain, Portugal, and Germany all have temporary visa options that allow you to live and work there as long as you have sufficient income or savings.

And if you REALLY want to just hop across the border, don’t forget about Mexico.

Hollywood has done tremendous work to brutalize Mexico’s reputation as a haven for violence. But that’s only true in certain parts of the country.

It would be as if foreigners judge the US based on antifa violence in Seattle and Portland, or the murder rate in downtown Baltimore. Most of the country is pretty quiet by comparison.

For instance, in areas like Mexico’s Yucatan state, crime is actually on par with the State of Wyoming.

Some of the countries I mentioned, including Mexico, Panama, and Portugal, allow permanent residency which can lead to full citizenship and a second passport.

If you happen to NOT be a US citizen, moving abroad generally means that you can completely divorce yourself from your home country’s tax system.

And if you’re a US citizen, moving to another country means that you can take advantage of the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion.

For tax year 2020, the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion means expats can earn up to $107,600 in wages without paying a dime of US federal income tax.

If you’re married, your spouse can qualify too. Plus there are generous housing allowances as well. So you can earn roughly $250,000 or more per couple and put almost all of it in your pocket.

Depending on which state you currently live in, you’d have to earn a pre-tax salary of roughly $400,000 in order to put the equivalent $250,000 in your pocket each year.

Not to mention, there are plenty of countries overseas where the cost of living is MUCH cheaper, where the schools, medical care, housing costs, etc. are incredibly low.

So there can clearly be a lot of financial benefit to living outside of your home country.

It’s a big world out there. There are so many options.

I’m not suggesting that you pick up and move. I am, however, suggesting that you at least think about it.

Consider what’s important to you: what are the most important characteristics of a potential new home?

Tax benefits? Nature? Safety and security? Medical care?

Whatever your priorities are, there are probably several options that tick the boxes.

And, as part of a good Plan B, it makes sense to at least have some of those options identified, regardless of whether or not you choose pull the trigger.

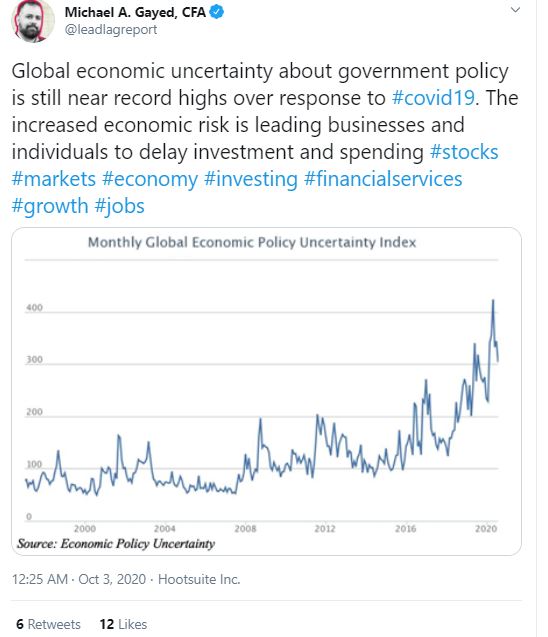

In recent weeks we have received a slew of requests for more insights about China’s changing role in the global economy, including its relationship with the United States, as well as the Federal Reserve’s ‘new’ shift towards average inflation targeting (AIT). Without question, both topics are important ones that reflect the increasing complexity of the current global macro environment. In our humble opinion, the U.S.–China relationship is likely to intensify further in the coming months, particularly ahead of the U.S. presidential election in November. However, given China’s importance to the global economy’s growth trajectory, we think there is still a significant benefit to investors who can thoughtfully deploy capital throughout Asia by leveraging an investment approach that is both local and global in nature. Meanwhile, we view the Federal Reserve’s new framework as a milestone announcement. In fact, AIT is likely the biggest shift in U.S. monetary policy since the introduction of quantitative easing (QE) at the end of the Global Financial Crisis. Not surprisingly, these two weighty topics — U.S.-China relations and the Fed’s recent shift in strategy — have significant long-term implications for all professionals of macro and asset allocation. Our base view at KKR is that inflation and rates stay low, and as such, we should heighten our focus on growth companies, yield, and collateral-based cash flowing stories. However, given that many central banks are now experimenting with helicopter money via direct deposits and looser inflation standards, we have also boosted our allocation to key markets such as Infrastructure, Asset-Based Finance, Gold, and parts of Real Estate.

“ There is a road, no simple highway, between the dawn and the dark of night ”

Grateful Dead American rock band

As summer winds down and autumn sets in, we typically welcome the onset of the ‘back to school’ season, which usually coincides with the end of summer vacation and the re-establishment of more formal routines. Yet, as we all know, that is not how we are going to remember the fall of 2020, given the challenges surrounding school re-openings, social distancing measures, and the troubling reality that at the end of August coronavirus cases surpassed the 25 million mark, which is more than a four-fold increase since just the beginning of June 2020.

At this point, we do take some comfort that medical professionals have learned more ways to manage the disease. That said, the overall case load in the U.S. remains quite high heading into the fall. Meanwhile, in Europe and Asia – after a fairly benign summer – cases have worryingly begun to tick up again in certain countries. Exacerbating all of this uncertainty is a fast-approaching and divisive election season in the United States and rising global tensions with China. These headwinds are offset by aggressive action by central banks, a sizeable slate of government transfer programs, and seemingly significant progress in the development of vaccines.

From our perch at KKR, we continue to balance the human tragedy associated with this disease, including sickness, death, job loss, and racial/social inequalities with our fiduciary responsibility to our limited partners to perform as investors on their behalf. This balance is certainly a complicated one, but as KKR’s founders Henry Kravis and George Roberts have been constantly telling us throughout the pandemic: If there was ever a time for us to intensify our efforts to “do well while doing good,” now is that time. To this end, we have tried to be present, engaged and to keep the channels of communication open with our investment teams, clients and our companies.

At the moment, there are two major issues that seem to dominate almost every “top down” discussion we have been having in recent weeks. They are as follows:

Looking at the big picture, we continue to believe we are in a decent environment for risk assets. Liquidity remains ample, and both real and nominal yields are near record lows. Meanwhile, corporate earnings are rebounding in the near-term faster than many investors think. Consistent with these improving trends, we are raising our 2020 and 2021 earnings per share for the S&P 500 to $125 from $115 and to $164 from $155, respectively. One can see the details on these upgrades in Exhibits 1 and 2. Based on these upgrades, we also lift our fair value target for the S&P 500 to 3,350-3,450 from 3,020-3,120 (Exhibit 4). From a GDP perspective, we too are making upward revisions. Specifically, we are lifting our 2020 forecast to negative 3.8% from negative 6.5% previously. Even with the recent surge in COVID cases during the summer, economic growth remained steadfastly resilient. That’s all good news.

EXHIBIT 1

Data as at September 18, 2020. Source: S&P, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

EXHIBIT 2

Data as at September 18, 2020. Source: S&P, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

EXHIBIT 3

Data as at September 24, 2020. Source: S&P, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

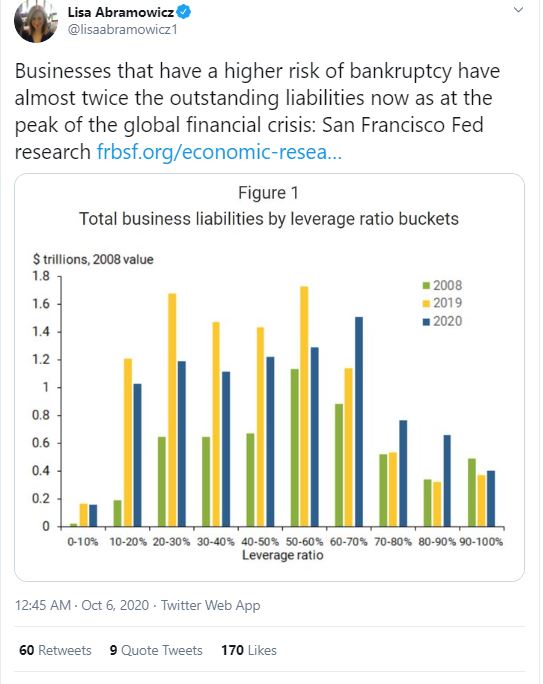

However, the “road” ahead will, as noted above, likely remain a bumpy one, not the “simple highway” for which many are hoping. Beyond the two topics we address in this paper — a shifting posture by the Fed as well as intensifying U.S.-China relations — there are others crosscurrents to consider, including a growing chance of a disputed election in the U.S. Meanwhile, the disruptive role that technology is playing in the global economy has never been bigger, a trend we see poised to accelerate further. There is also a record increase in debt loads, which ultimately will affect growth (Exhibit 6). Finally, after a historic period of outsized activity by the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury relative to its global peers, it feels like the secular bull market in the U.S. dollar and its interest rate advantage may now have finally run its course. We do not make these statements lightly.

EXHIBIT 4

Notes: Key Assumptions – 2020e EPS growth = -24% (vs prior estimate of -30%); Long-Term Risk-Free Rate = Current 10y U.S. Treasury yield = 0.7% pull; up to 0.7% Long-Term Growth Rate = 1.2% (50bps higher than the risk-free rate to account for the new Fed regime); Cash payout (dividends and buybacks) falls to 80% (better than GFC levels of 65%) and recovers back to 90% by 2025. Key Metrics – Fair Value Estimate = (3,350-3,450); high case is around 3,900 and low case is <3000; 2021e EPS = $164/share; P/E Multiple on 2021e EPS = 21.4-22.0x (versus prior estimate of 19.5-20.1x).

EXHIBIT 5

Data as at July 30, 2018. Source: OECD, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 6

Data as at April 14, 2020. Source: IMF, Haver Analytics.

Against this backdrop, we believe a thoughtful macro framework becomes even more important than in the past. From our perch at KKR, we believe that CIOs will need to bring down loss rates across all products, given our more muted expectation for forward returns (see Exhibit 44 in our recent Insights note, The End of the Beginning). Somewhat ironically, this requirement to bring down loss rates is occurring at a time when we think most allocators will actually need to take more risk – not less – to achieve their stated goals. Given the low cost of financing, some CIOs will pivot towards adding some leverage to boost overall returns. We are not opposed to this idea, but we strongly believe that getting the right asset allocation with the right top-down themes will become the most important differentiator over the next five years.

So, where to invest? For our nickel, we continue to advocate even more strongly for a mix that is overweight secular growth companies that can also compound their earnings, which we view as an increasingly rare achievement (Exhibits 7 and 8). Also, remember that real rates are now deeply negative, which increases the value of upfront cash flows that are well in excess of the current rate of inflation. From a thematic perspective within this bucket of our asset allocation, we favor e-commerce, digitalization, pet care, personal safety, and nesting.

EXHIBIT 7

Data as at August 3, 2020. Source: Datastream, I/B/E/S, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

EXHIBIT 8

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Factset, MSCI, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

We also favor assets linked to nominal GDP with upfront cash flow. We do not see inflation surging in the near-term, but current fiscal and monetary policies are unprecedented. Recent comments by Federal Reserve members about average inflation targeting only increase our conviction that now is the time to buy a little extra insurance. As a result, we have moved to an even more overweight position in Asset-Based Finance in Credit, Infrastructure, Logistics, and parts of Real Estate. Finally, we continue to advocate for a significant slug of non-correlated assets, including Gold.

EXHIBIT 9

Data as at August 14, 2020. Source: Barrons, Bloomberg.

Importantly, though, as Exhibit 9 shows (and we noted earlier), being in the right verticals with the right themes likely matters more than ever. So, our goal at KKR is to continue to effectively marry our macro themes with our micro insights and to use our portfolio construction tools to deliver investment outcomes that we believe are reflective of our firm’s 44-year history as not only a leading alternative investment manager, but also as a thoughtful partner to our clients.

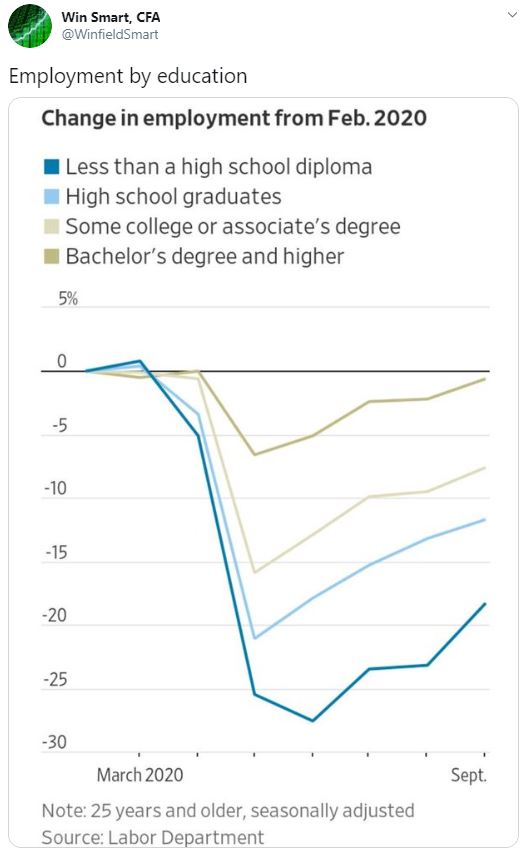

Coming out of the July FOMC meeting, the headline was that there were no policy changes. However, that is not how we interpreted events. In particular, what was most interesting to us was Chairman Powell’s press conference, where he continued to elevate his concerns for the U.S. real economy amid the ongoing pandemic — flagging, for example, the significant backtracking in job creation for minorities since February (Exhibit 10). Indeed, we think that the Fed is heavily influenced by the unsavory skew of recent unemployment trends. The reality is that unemployment – even after adding back nearly 11 million jobs since March — is still running just below where it was at the peak of the Global Financial Crisis. Without question, these elevated levels of worker displacement are making a huge impression on the way the central bank governors think about policy for the foreseeable future.

EXHIBIT 10

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 11

Data as at August 7, 2020. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Haver Analytics.

By comparison, Powell has consistently downplayed the substantial healing we have already seen in financial conditions, emphasizing that his prime focus is keeping credit markets open and liquid. Indeed, despite tightening credit spreads, he has been unwavering in his message that “preserving the flow of credit is essential” to minimize the damage caused by the virus. In fact, even after credit spreads had almost fully normalized to the pre-pandemic range, the July statement by the Federal Reserve announced that, “To support the flow of credit to households and businesses, over the coming months the Federal Reserve will increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities at least at the current pace to sustain smooth market functioning, thereby fostering effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions.”

EXHIBIT 12

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 13

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 14

Data as at September 3, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 15

Note: High-Wage = Information Services, Utilities, Finance, Prof Services And Mining/Logging; Medium-Wage = Wholesale Trade, Construction, Manufacturing, Education/Healthcare, Transport; Low-Wage = Retail Trade, Leisure/Hospitality. Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Haver Analytics.

At the annual Jackson Hole summit (held virtually in 2020) in late August, the Fed – as we indicated earlier – shifted its inflation mandate towards an average goal of two percent. In our view, the lion’s share of central bank committee members now believe that inflation is so structurally low that the committee’s change “reflects [their] view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.” This statement is important because it reveals two things. First, it suggests that, despite the Fed’s dual mandate, it appears to be intensifying its focus on employment relative to inflation. In fact, Powell recently stated that, “This change (in the inflation mandate) reflects our appreciation for the benefits of a strong labor market, particularly for many in low- and moderate-income communities.” Second, when it comes to future inflation trends amidst further downward pressure on wages, he certainly sees a negative skew. Recent trends support this view as inflation has only reached two percent for six months during the last 10 years, despite the U.S. reaching a generational low in its unemployment rate in 2019.

EXHIBIT 16

Data as at September 11, 2020. Source: BEA, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 17

Data as at July 31, 2020. Source: BEA, BLS, Haver Analytics.

Another important consideration is what the market is discounting. As we show in Exhibit 23, the rates market is actually embedding potentially negative fed funds in coming quarters. This set-up is significant because it means that Chairman Powell must remain extremely dovish just to prevent a ‘taper tantrum’ situation from unfolding, we believe.

The Fed then held what we view as a ‘watershed’ meeting on September 15th, 2020. At this meeting it officially pivoted to an average inflation targeting framework and committed to formally maintaining rates at the zero lower bound until inflation rises above two percent with solid labor market trends. We believe that there are six main conclusions for investors to digest. They are as follows:

EXHIBIT 18

Data as at September 16, 2020. Source: FOMC, Bloomberg, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

As we look ahead towards the winter, we still expect an extension of the current regime of declining U.S. real yields amid pinned nominal rates and rising inflation expectations. Importantly, 10-year inflation expectations have recovered significantly to 1.77%, but current levels still remain below the Fed’s stated two percent goal. As such, we now see further scope for break-evens to grind higher and real rates to grind lower after the Fed fleshes out in a credible manner how it will implement flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT).

EXHIBIT 19

Data as at September 3, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 20

Data as at September 3, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 21

Data as at July 31, 2020. Source: Cornerstone Macro.

EXHIBIT 22

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: Federal Reserve Board, JP Morgan, Bank of England, OECD, IMF, World Bank, Bank for International Settlements, Haver Analytics, Bloomberg.

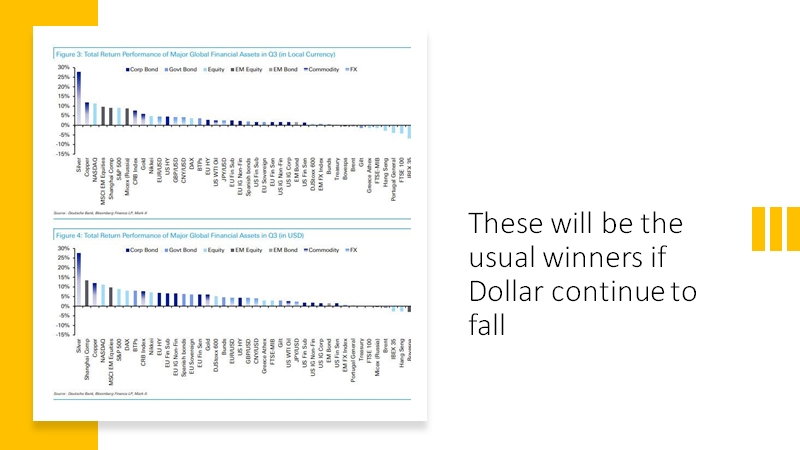

What does all this policy rhetoric mean for asset allocation on a go-forward basis? For starters, it means monetary policy in the United States will remain significantly accommodative for quite some time. As part of this worldview, we think that U.S. dollar assets will depreciate more so on a relative basis than they have during the past 5-10 years. In particular, such negative U.S. real rates are supportive for the euro to increase to at least 1.25 relative to the dollar. We also see the potential for many emerging market currencies to gain ground versus the dollar as well. To this end, my colleague Frances Lim has done some interesting work to show that, despite significant debt loads in China, U.S. debt loads have increased even more. All told, the U.S. has spent 44% of its GDP to try to temper the adverse effects of the coronavirus. Against this backdrop, we believe that the Chinese renminbi seems well poised to appreciate against the U.S. dollar, which could bring a major change in the attitude of global investors.

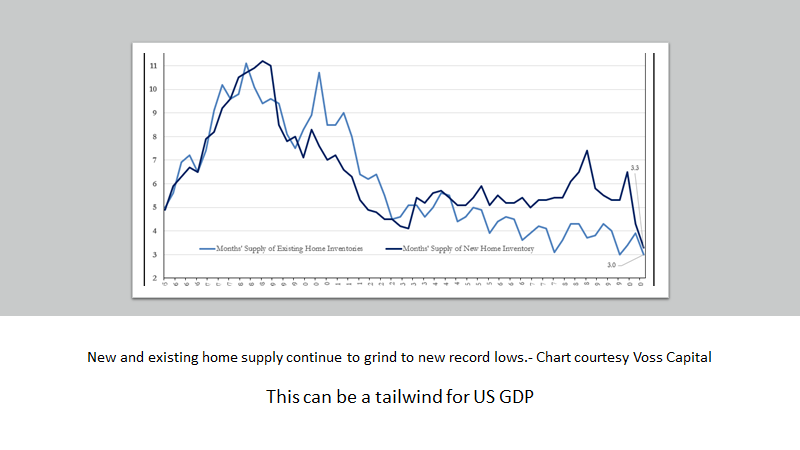

Meanwhile, within Private Credit, we think that investors should be aggressive around sourcing hard asset-based investments with upfront cash flows (e.g., Asset-Based Finance). We are currently seeing a compelling opportunity set for providing solutions via housing platforms where there are supply-demand imbalances pressuring both home prices and rents, or lending against the embedded value of an asset (EV) with favorable coupons. Along those same lines, we also like asset classes that tend to pay relatively higher excess coupons for which there are sound underwriting disciplines and fundamentally driven borrower behavior. One such example includes auto loans, for which the backdrop of personal mobility and independence is a near term tailwind; we also like that, if underwritten properly, there is significant asset value in many autos that can serve as collateral, particularly when the auto is viewed as a personal safety item for the driver (e.g., a commuter).

EXHIBIT 23

Data as at September 11, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 24

Data as at September 11, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 25

Data as at September 11, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 26

Data as at September 11, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

The environment we envision also means that Infrastructure should do well. Coupled with rapidly aging populations that are not confident that they will have enough money to retire, the desire for income producing investments should only increase in our view. We believe these trends are secular, not cyclical, and will likely continue to positively affect valuations of “growth-oriented” yielding securities or investments, including global infrastructure. Last mile build-out in optical fiber has been a significant overweight for us, but we are also seeing a growing number of infrastructure opportunities emerge from over-levered corporates. At the moment, Europe and Asia have been the most active areas, but we do also expect the U.S. to participate in our deconglomeratization thesis. As Exhibit 28 shows, our work suggests this transition towards more simplicity in corporate structures generally leads to a significant increase in value.

EXHIBIT 27

Data as at September 1, 2020. Source: MSCI, Bloomberg.

EXHIBIT 28

Data as at August 6, 2019. Source: MSCI, Factset Global, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

On the traditional equity side of the portfolio (and despite the cyclical rebound we are forecasting), the current structural global GDP slowdown is having a profound impact on the ability of companies to grow. All told, the percentage of companies in the MSCI All Country World that are poised to grow eight percent or more has fallen sharply to 16% in 2020 from 45% during the 2000-2001 period (Exhibit 7). So, our view is to find companies that have established cash flowing business models with identified economies of scale that will result in material improvements in cash flow and book value as these businesses grow in size. We also think that these companies should have clearly defined sources of support for those cash flows, including access to growing end markets, clear ability to scale in production or distribution, brand loyalty, and defensible margins. This underscores our view that owning some secular growth in the portfolio has become of paramount importance. In terms of where to invest behind our favorable outlook on secular growth stories, we currently favor several regional themes over global ones, including business services, logistics, digitalization, payments, and automation.

Our bottom line: Led by outsized U.S. monetary policy that is more flexible in nature and a surge in fiscal stimulus, we are at an inflection point in the global capital markets, one that requires a rethinking of traditional asset allocation. Beyond the more restricted role that government bonds can play in a diversified portfolio (see our recent Insights note, The End of the Beginning), we are using this piece to strengthen our view that the recent decline in the U.S. dollar will emerge as a more permanent feature during this recovery. Just consider that real yields in the U.S. are now on par with Europe – which makes the euro more competitive – while nominal yields greatly favor China’s currency (see below Exhibit 46). Consistent with this view, we are also suggesting that weightings to European and Asian Private Equity likely need to trend higher. We also believe that collateral-based, private investments like Infrastructure, Real Estate Credit, and Asset-Based Finance will likely be re-rated upward in the coming quarters if we are correct about the intentions of the Federal Reserve.

However, the Fed’s revelation that it will monitor financial stability means that the background will be less of a one-way trade in favor of risk assets. In particular, the Fed is now starting to publicly remind everyone that monetary policy is intended to ‘fix’ the economy, not continually bolster financial asset prices. Hence, it has made the decision to flag ‘financial stability’ more aggressively in its mandate. Walking this line as a committee will not be easy. Indeed, we view the dissension in September by Fed governor Robert S. Kaplan as an important signal for the investment community to watch. Were more Fed governors to adopt his viewpoint, it could quickly reduce some of the excess froth that now appears to be building up in some of the more speculative parts of the debt and equity markets.

In recent weeks, investor’s interest in Asia, China in particular, has – not surprisingly – surged. This heightened level of inquiry makes sense to us, given ongoing technology disputes, noise around the South China Sea area, and a continued ‘blame game’ around the onset of the coronavirus. Given this backdrop, we thought it might make sense to discuss our current thinking on several major trends in China, including areas where we still have high conviction and areas where our thoughts might have changed or become more conservative.

In terms of what has not changed in our outlook, there are several long-term trends to embrace, we believe. First, we still expect China to remain the dominant force in global growth, even in the slow growth ‘world’ we envision. One can see that China alone makes up about one third of global growth; with its immediate trading partners across the emerging markets that proportion climbs to almost 75% (Exhibit 29). That part of the story has not changed.

EXHIBIT 29

Data as at April 16, 2020. Source: IMFWEO, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 30

Data as at April 9, 2019. Source: IMFWEO, World Bank, National Statistical Agencies, Haver Analytics, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

We also believe that China remains steadfastly committed to aggressively internalizing its economy. Of late, President Xi Jinping has been promoting his new ‘dual circulation’ strategy, which emphasizes domestic manufacturing and services for the domestic consumption economy. In other words, the country is pivoting from one focused on international trade/exports to one that is focused on self-sufficiency for its burgeoning consumer market and domestic businesses. However, as we show in Exhibit 31, this transition actually began to take place immediately and steadfastly after 2007, the exact point when China realized it needed – for both economic and national security reasons – to pivot away from an export-driven model that was largely dependent on the U.S. consumer.

Fast forward to today, and exports as a percent of GDP are now just 17%, compared to nearly 36% in 2007. Moreover, the type of exports has shifted, as China has boosted the proportion linked to higher value-added products (read China 2025) to nearly 60% from around 44% in 2008 (Exhibit 32). In our view, the coronavirus as well as the recent trade spats will only reinforce China’s commitment to this initiative.

EXHIBIT 31

Data as at August 31, 2020. Source: China Customs, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 32

Data as at December 31, 2019. Source: China Customs, Haver Analytics.

Importantly, we see more running room ahead, particularly given the huge size of China’s middle class. One can see this in Exhibit 30. As part of this growth, we expect the trends towards digitalization, e-commerce, fintech, and online experiences to accelerate. Moreover, we think the collective arrival of the Internet of Things (IOT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and 5G (5th Generation Connectivity) mark a pivotal point that will reshape the global economy. Indeed, while many hoped that the AOL-Time Warner merger would herald in the Internet age in 2000, it was missing the processing speed, swaths of data, and mature algorithms to fuel AI. Today, however, we believe 5G, AI and IOT will revolutionize every industry. We now have massive amounts of data, a technologically skilled workforce, high tech communications infrastructure, and high speed processing power. As a result, 5G will remain a key battleground, and as such, China’s ability to differentiate itself during its rollout/adoption could be significant to the country’s overall growth and competitive positioning in the global economy.

On the other hand, there are several important influences that have changed direction in recent months. The first is China’s role in the global liquidity picture, and then its response to the coronavirus in particular. Specifically, whereas China used record amounts of stimulus essentially to reinvigorate the entire global economy in 2008, this cycle, it has been the United States leading the charge in terms of throwing the greatest amount of liquidity at the problem. One can see this in Exhibit 33.

EXHIBIT 33

Data as at June 30, 2020. Source: Cornerstone.

EXHIBIT 34

Data as at July 27, 2020. Source: Haver Analytics.

Heightened geopolitical tensions are also changing the way China and its trading partners think about their role in the global supply chain. Importantly, we do not believe that the current geopolitical frictions centered in the Indo-Pacific region are an anomaly – the product of the particular personalities presently in power or election year dynamics in the U.S., although the latter is certainly exacerbating certain trends. Rather, we see great-power competition – not only between China and the United States, but between China and other major powers – as an enduring, transformational force on the international stage, akin to globalization, that is likely to play out for the foreseeable future.

Without question, this transformational shift will definitely impact supply chains. To this end, we recently spent time analyzing some excellent work done by the U.S.-China Business Council as well as comparing best practices across our nearly 200 portfolio companies. As we show in Exhibit 35, the punchline is that many companies are slowing down their investment in China. Some of this shift in sentiment is linked to heightened geopolitical tensions, while some of it stems from the aftermath of COVID-19. As we show in Exhibit 38, research and development too has fallen dramatically.

Interestingly, though, our conversations with many CEOs operating in China suggest that there is an important bifurcation occurring. Specifically, management teams who believe that their companies have built competitive advantage – either by product or by process – are actually ramping up their investments in China to try to capture more of the market. The goal, we believe, is to extend their lead over local players in such a way that they build a competitive, sustainable moat around their businesses. This viewpoint is significant, as large U.S. multinationals have $900 billion in assets and more than $500 billion in book value now located in China, according to a recent report by the Economist. By contrast, smaller and more marginal players, particularly those who today face a more formidable local competition, are now pulling back more aggressively than in the past.

EXHIBIT 35

Data as at June 2020. Source: U.S. China Business Council Member Survey.

EXHIBIT 36

Data as at June 2020. Source: U.S. China Business Council Member Survey.

EXHIBIT 37

Data as at June 2020. Source: U.S. China Business Council Member Survey.

EXHIBIT 38

Data as at June 2020. Source: U.S. China Business Council Member Survey.

We also do not ascribe to the bearish view that all supply chains will exit China immediately. There are several influences to consider. First, our contacts on the ground inform us that local Chinese officials are working very hard to create an attractive environment in which U.S. multinationals can continue to operate. Consistent with this view, we are increasingly hearing of more approvals, particularly in financial services, for foreign operators to own majority stakes in China.

Second, because China has such a strong and proficient infrastructure, it is hard to replicate the ‘supply chain pods’ that exist inside China elsewhere. As such, while some capacity is either re-shoring or moving to other low costs countries like Thailand, the majority of those we polled in our informal survey are keeping more than 70% of their production in China for the foreseeable future. This reality is one of the main reasons we are not surprised that China has continued to gain market share in the export market. One can see this in Exhibit 39.

EXHIBIT 39

Data as at July 2020. Source: China Bureau of National Statistics, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 40

Data as at July 2020. Source: China Bureau of National Statistics, Haver Analytics.

From a strategic standpoint, China is also changing the way it thinks about its capital markets. Remember that as it continues its transition from a fixed investment economy to a services and consumption based one, China will almost inevitably run a current account deficit. If it does, it will need to fund that ‘hole’ in its current account with positive flows into its capital account. To do this, it must either attract foreign direct investment and/or portfolio flows. Our ‘gut’ instinct is that China will do both.

EXHIBIT 41

Note: The size of stock market refers to the total market capitalization of domestic listed companies. Data as at September 23, 2020. Source: World bank global financial development database, BIS, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

EXHIBIT 42

Note: The size of bond market refers to total securities outstanding including domestic and international. Data as at September 23, 2020. Source: World bank global financial development database, BIS, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

EXHIBIT 43

Data as at June 30, 2020. Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 44

Data as at October 7, 2019. Source: IMF, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 45

Data as at March 31, 2020. Source: BIS, Haver Analytics.

EXHIBIT 46

Data as at September 24, 2020. Source: Bloomberg.

Importantly, with the size of the capital markets being quite small relative to size of GDP, there could be significant room for growth if China were to catch-up in relative size with some of its developed market peers. While China’s banking system as a share of GDP of 292% is much larger than that of the U.S. (119%), its bond market is much smaller. Specifically, China’s bond market is now just 114% of GDP, compared to 193% in the United States, 252% in Japan, and 92% in Germany. In our view, herein lies the opportunity, we believe, particularly given China has so much higher real and nominal rates (Exhibit 46). If we are right, China will work hard to ensure that its bond market, which can be supported by more foreign capital, can replace its bank lending market as a primary source of funding growth and pricing risk. The key, of course, will be assuring investors that their capital will not get stuck in China, an issue of concern for many global investors with whom we speak.

On the equity side of the Chinese capital markets, we are also optimistic about China’s ability to import foreign capital. Already, since 2019, China’s A-share representation in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has quadrupled from five percent to 20%. Yet, even with this sizeable increase, the size of China’s capital markets is still comparatively much smaller than its peers. All told, its stock market capitalization stands at 59% of GDP, which is much lower than that of the U.S. at 148% of GDP, Japan at 122% of GDP, and Australia at 107% of GDP (Exhibit 41). Moreover, as Exhibit 47 shows, recent new issue activity has remained extremely robust, despite rising geopolitical tensions, a trend we expect to continue.

EXHIBIT 47

Data as at June 19, 2020. Source: CEIC, Morgan Stanley.

EXHIBIT 48

Data as at June 11, 2020. Source: Citigroup.

So, in sum, while Frances Lim and I think we are at an important inflection point for U.S.-China relations, many of the current trends that led to this inflection point have been bubbling up for a decade or more. In terms of key areas of focus, our top belief is that investors should expect China to continue to internalize its economy. A consumption economy lifts millions out of poverty, which helps to ease social unrest. A consumption economy also makes China less dependent on others, including the United States. “Domestic circulation,” or the intent to source more parts locally, will also drive more innovation as well as growth in new Chinese industries. However, as consumption becomes more important, so too will the ability to attract foreign capital. In our view, understanding the nuances of this transition will be a critical one for all global investors.

EXHIBIT 49

Data as at December 31, 2016. Source: JPM Asset Management, UNCTAD, World Bank, UN, U.S. Treasury, Baribieri/Keshk COW Trade data, U.S. Trade Representative Office, Setser (CFR), Bank of England, St. Louis Fed, Eichengreeen (Berkeley), Howson (Princeton), East-West Center, O’Neill (CNA), Ritschi (LSE) Accominotti (LSE), Wilkins (FIU), Villa (CEPII).

EXHIBIT 50

Data as at December 31, 2019. Source: Goldman Sachs.

Nonetheless, there will likely be a higher risk premium associated with investing in China. In particular, tensions around economic prowess, national security, human rights, and ideology likely mean that investors will need to approach China with a more nuanced lens, one that requires both local and global perspectives. For example, as we show in Exhibit 50, China’s dominant position in the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients is already being questioned by national security experts in Europe and the United States. Parts of supply chains too as noted earlier may be rethought.

EXHIBIT 51

Data as at May 29, 2019. Source: KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

As we mentioned at the outset of this Insights note, the path forward for China could be a rocky one, but there is a lot we can learn from where China has been in order to invest behind where it will be going in the future. Indeed, as Confucius said, “study the past if you would define the future.” In our humble opinion, after traveling to China for nearly three decades, never have these words of wisdom been truer.

EXHIBIT 52

Data as at July 31, 2020. Source: Deutsche Bank, The Economist.

As we head into the fall, we feel confident about the upside potential for our global investors if we can correctly marry our macro themes with the micro opportunities that our investment teams continue to uncover. However, as we detail in this piece, understanding the long-term implications of the change in Fed policy and also in the U.S.-China relationship is paramount to that success. Importantly, similar to the introduction of QE as an inflection point in monetary policy during and after the GFC, we view the Fed’s new inflation framework as another important milestone.

Our base view is that inflation and rates will remain low. So, from an asset allocation perspective, investors should increase their focus on growth companies, yield, and collateral based cash flowing stories. However, given that many central banks are now experimenting with helicopter money via direct deposits and looser inflation standards, CIOs should likely have more inflation-based protection in the mix. By comparison, given how deeply negative real interest rates are, the penalty for owning cash has gone up. As a result, periodic dislocations in the credit markets should be consistently bought, particularly at the short end of the curve. Finally, while the backdrop is still a good one for risk assets, the Fed’s intensifying focus on financial stability should serve as an important warning shot that more volatility and less consistent gains lie ahead.

EXHIBIT 53

Data as at August 28, 2020. Source: Cornerstone Macro.

EXHIBIT 54

Data as at June 30, 2020. Source: Bloomberg, Haver Analytics, Cambridge Associates, KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation analysis.

On the China front, we expect heightened tensions to continue. Key to our thinking is that the U.S. and China are redefining their policies around a variety of different issues, including economic ties, ideology/human rights, national security, and law enforcement. Because there are so many differing constituents with separate agendas involved in the debate, the probability of near-term harmony is low. Largely, this is why we have dedicated so much of our research effort to better understand China’s long-term plan and what it means for the global economy and capital markets.

Overall, we view the current environment as an attractive one for investors who can translate their thematic macro work into actionable micro themes. The key, as we have described in all our recent post-COVID Insights pieces including this one, is to focus capital deployment on areas, including sectors and themes, where there is not only above average GDP growth but also the ability to translate the revenues into high cash flow returns. Without these disciplines, we believe that the ability to earn outsized returns during the next five to seven years is now much more limited (Exhibit 54).

https://www.kkr.com/global-perspectives/publications/road-ahead

Via Zerohedge

Back in July, one of the most respected credit strategists on Wall Street caused stunned gasps across the financial world, when he admitted that he is “a gold bug.” Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid may have been forever cast out of the ranks of polite, non tinfoil hat/conspiracy theory society when he said that in his opinion, “fiat money will be a passing fad in the long-term history of money”, a shocking admission (if one that many of his peers secretly harbor) for most financial professionals who are expected to tow the Keynesian line and always believe in the primacy of fiat and its reserve currency, the US Dollar.

Of course, for those who have been following Reid’s writings over the past few years (we feature his Daily Morning Reid note in our AM wrap), that admission was hardly a surprise: for much of the past decade, he has been closest to saying what most rational, clear-thinking people on Wall Street – and elsewhere – think and believe, yet are afraid of speaking it for fears of direct and indirect retaliation from an established monetary and financial system which has zero tolerance for anyone casting doubts over its viability (the fact that he works at Deutsche Bank is an added bonus).

For those unfamiliar with his work, some of his more notable recent writings can be found below:

Reid’s natural curiosity and eagerness to ask the right question even if it provokes established financial dogma is why we read his latest must-read long-term asset return study titled appropriately “the Age of Disorder” with great interest, and why we republish the executive summary in its entirety because for better or worse, he gets it right (we will have several follow up posts to follow).

* * *

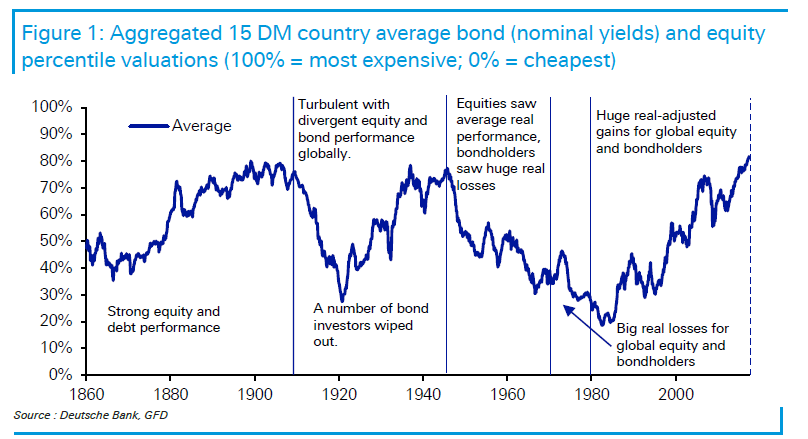

Economic cycles come and go, but sitting above them are the wider structural super-cycles that shape everything from economies to asset prices, politics, and our general way of life. In this note we have identified five such cycles over the last 160 years, and we think the world is on the cusp of a new era – one that will be characterised initially by disorder.

Not all disorder is ‘bad’. Indeed, if the themes of the world economy swing like a pendulum, then it may be that some have swung too far from a ‘sensible centre’ and are due to revert. This can have a cleansing effect. What is worrying, though, is that several themes appear poised to revert at a similar time. This is the point – that simultaneous changes to structural themes will create a level of disorder that will define a new era.

Before we review the key themes of the upcoming “Age of Disorder”, we must note that while some historical super-cycles have begun and ended abruptly, others were slower to evolve and end. The most recent era – the second era of globalisation, during 1980-2020 – is much more like the latter. It started slowly and has been gradually fraying at the edges over the last half-decade. The end of this era has been hastened by Covid-19 and – when, in years to come, we look at the rearview mirror – we may see 2020 as the start of a new era.

By our measure, there have been five distinct eras in modern times, with a sixth likely starting this year:

The era of globalisation to we are likely waving goodbye saw the best combined asset price growth of any era in history, with equity and bond returns very strong across the board. The Age of Disorder threatens the current high global valuations, especially in real terms. We believe this coming new era will be marked by at least eight themes, which we will briefly summarise in this executive summary and then expand upon in the full note.

Although some of these themes have been around for some time, it is only recently that they have begun to feed off each other to hasten the demise of the second era of globalisation. Their increased interaction has thus created the conditions to start their own new era of much change.

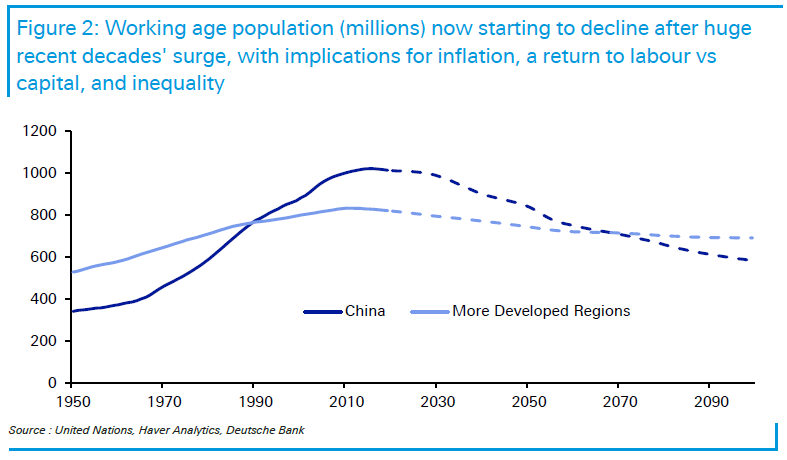

The key to understanding this new age of disorder, then, is to see how its themes emerged during the most recent era of globalisation. This was the era that began around 1980, when the world accelerated the move to abolish regulations and capital controls, which subsequently boosted free trade (and global capital flows) and begat a more liberal world order. Global demographics massively supported this phenomenon and ensured a huge increase in workers, many of them from China and other low-income countries. By the mid-1980s, the second era of globalisation was in full flow.

This era was win-win for most of the globe, and everything fell into place over the next three to four decades. Inflation fell largely due to a huge surge in workers (now behind us), and there was also downward pressure on wage inflation due to global labor market integration. In addition, there was help from direct central bank policy, including increased independence around the world. Lower inflation meant lower bond yields (real and nominal) and lower interest rates, and this all allowed for ever-higher equity valuations and profits. As a result, equities generally performed very well relative to what was slowing developed-market growth.

The cracks in this era began to emerge after the GFC, which revealed that ever-higher leverage had papered over the problems that globalisation had created in many Western countries. Firmly in the spotlight were issues including low real wage growth, the outsourcing of many low-paid jobs, and increased inequality. In response, authorities used heavy intervention (especially monetary) to prop up the existing system (rather than reform it), but populism and resentment built. The Brexit and Trump victories were manifestations of this anger in the UK and US, but populism increased across the globe. It was then that most people realised the era of full-feted globalisation was certainly fraying and the problematic issues it had incubated were about to take centre stage.

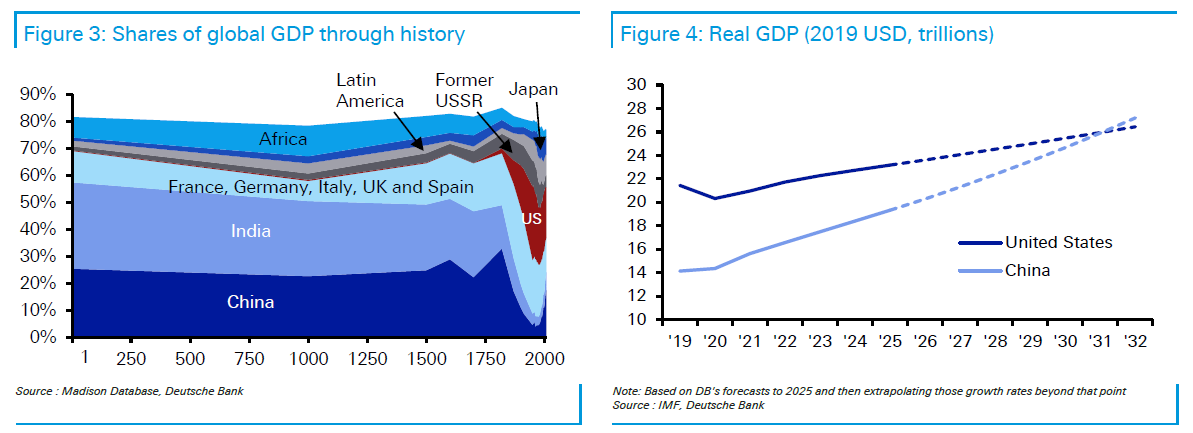

As the Age of Disorder begins, we believe one of the biggest issues will be the political tension between the US and China. Indeed, this should characterise the era of disorder because China has been at the heart of the most recent era – that of globalisation. The future of this relationship can only be forecast by understanding the past. We delve into this in more detail later, but to summarise: China is looking to restore the position it held for much of history as a global economic powerhouse. To illustrate, from two thousand years ago until the early nineteenth century, the country represented around 20-30% of the global economy. It then suffered under colonial powers, particularly in the century before Mao established the modern Chinese state in 1949. By the early 1960s, China’s share of the global economy hit an all-time low of 4%. It is now back to 16%.

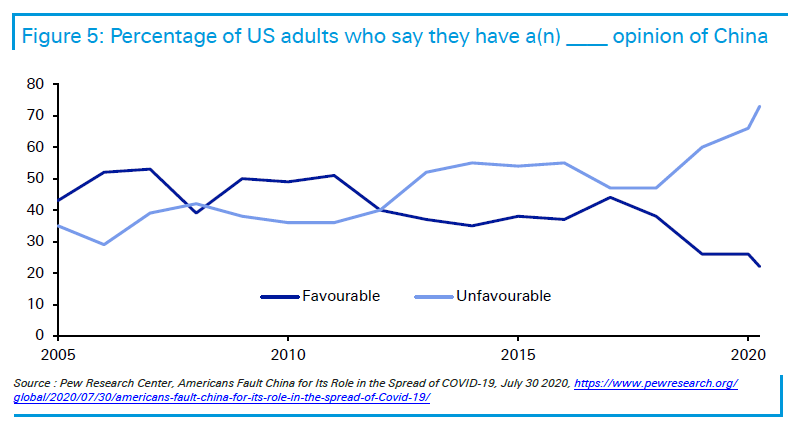

While China’s fortunes rapidly grew during the era of globalisation, so too did tensions with the West. Partly, this came from the incorrect assumption in the West that as China developed it would increasingly become more Western in its outlook and values, and fully integrate into the liberal world order, which contains much American architecture. With hindsight, this was naïve as China has a long, proud and powerful history with its own values.

A clash of cultures and interests therefore beckons, especially as China grows closer to being the largest economy in the world. From the West’s point of view, China would not be in its current position if the West had not accepted China into its economic orbit during the latest era of globalisation. Now, the Covid-19 pandemic will likely speed the symbolic point at which China overtakes the US economy as the largest in the world. China has seen a post-Covid V-shaped recovery already, while it has become obvious that recovery in many Western countries will be a lengthier process. Assuming its current trajectory continues, China could become the world’s largest economy around the end of this decade or soon thereafter. Regardless, the crossover point with the US seems only a matter of time.

As the economic gap between the US and China narrows, many worry about the so-called Thucydides Trap. This refers to the fact that on 16 occasions over the last 500 years, a rising power has challenged the ruling one, and on 12 occasions it ended with war. While a military conflict today seems highly unlikely, an economic battle is likely to ensue, with the benign global trading conditions of the globalisation era likely to be resigned to the history books. The result of the US election in November is unlikely to change the direction of travel. Over the course of this decade, relations will likely deteriorate into a bipolar standoff as both the US and China seek to prevent encirclement by the other. Companies that have embraced globalisation will be stuck in the middle if relations sour as we fear.

The second theme of the Age of Disorder is that the 2020s could be a make-or-break decade for Europe. The strains on the continent were evident prior to Covid-19, but the virus has probably reduced the chance of the 2020s being a muddle-through decade like the 2010s. The economic divergence between countries will likely be even more pronounced and, as such, it feels like the probability of both integration and disintegration has increased over the last six months. On the one hand, the Recovery Fund is a genuine and welcome step in the right direction, but it needed to be. On the other hand, given the economic issues ahead, further measures will probably become necessary in the years ahead to prevent maximum disorder.

Even if further economic stimulus can be negotiated as needed, it is likely to be done against a backdrop of consistent volatility and brinkmanship, particularly if domestic politics across the continent gravitate away from those consistent with further EU integration. With the Covid economic shock, that must be a greater possibility now. So the chances of muddling through for Europe have decreased, while the potential for both further integration or disintegration has increased post-Covid. Even if integration wins out, it may still take an acute threat of disintegration to concentrate political minds.

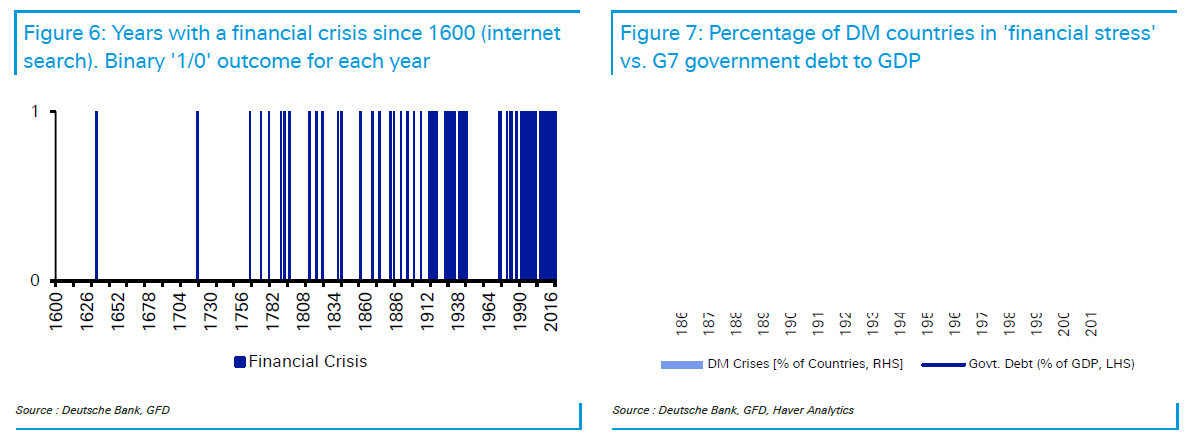

A key problem Europe faces is that many of its countries have too much debt, and this leads straight to our third theme in the Age of Disorder. Far from being just a problem in the European periphery, debt is a global issue – and it is only because central banks have distorted free markets that global borrowing can be financed at a viable interest rate. Given central banks have committed to underwriting the post-Covid recovery, they will have an even more outsized role over the years ahead. Our work in a previous long-term study “The Next Financial Crisis” suggests that periods of higher debt lead to a higher intensity of financial shocks and crises. This trend will be amplified by the Covid-19 crisis and means we will likely see more crises, more disorder and even more money printing in the years ahead. Yes, lower interest rates mean we can run with more debt, but a high-leverage society is always likely to be more shock-prone.

The extent to which we can reduce the huge global debt burden depends heavily upon the fourth theme in the Age of Disorder – inflation. On this topic, DB is still split on whether the debt and Covid-19 crises will be inflationary or disinflationary. Although this team is in the inflationary camp, we acknowledge that the outcome is path-dependent. If we move to a MMT/helicopter-money type world, where both fiscal and monetary policy are expansionary, it is pretty easy to see a jump in inflation. For us, Covid-19 has forced global policy makers to cross the Rubicon with regards to expansionary fiscal policy, and it is unlikely that they’ll go back to the austerity of the early-2010s – and with ultra-loose monetary policy almost guaranteed, this will put us in a completely different world order to that seen previously and create a very different macro environment. However, if we’re wrong and governments prioritise the repair of their balance sheets, then – even if central banks keep printing – we are likely to be stuck with low inflation for a longer period. With so much debt, such a scenario will also almost certainly ensure its own elements of disorder ahead.

Regardless of which outcome materialises, it feels that the ability of policymakers to perfectly calibrate inflation towards target in a post-Covid world will be incredibly difficult given the size of the opposing forces. So we expect a higher probability of more extreme outcomes going forward.

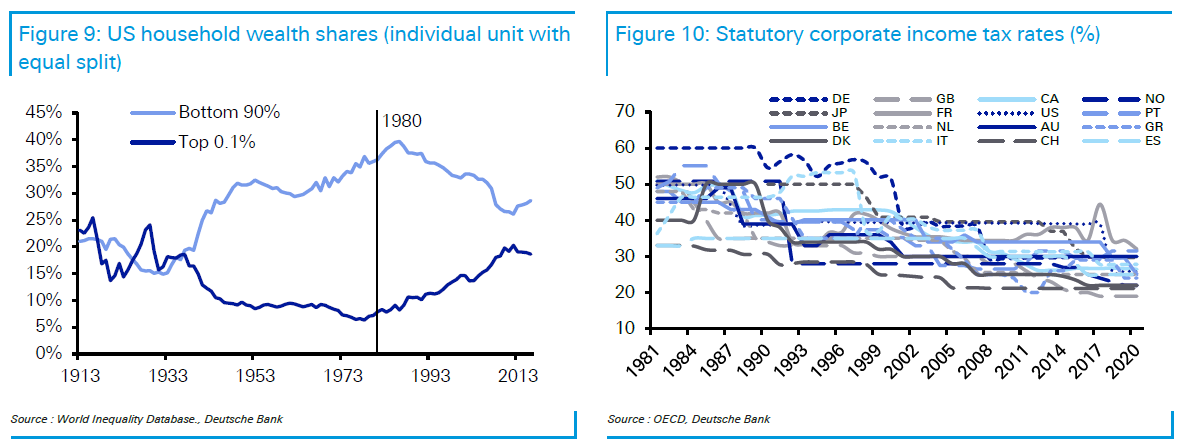

As the outcomes become more extreme, they will heavily influence how progress is made on inequality – our fifth key theme. It may initially worsen, but the need to pay for the Covid shock, and perhaps the reduction of globalisation, may encourage governments to increase taxation on those with deeper pockets. This is likely to be biased towards the highest-paid individuals, but also companies as they have benefited from a race to the bottom in corporate tax in the globalisation era. Technology firms are already attracting greater attention on this front, especially as they have largely benefited from the pandemic.

The discussion of inequality within and between countries will not be limited to wealth and income. In fact, an issue that is quickly emerging as a political force is the intergenerational gap. This is our sixth theme in the Age of Disorder. This segment of inequality has been allowed to build and build in the globalisation era. The general assumption is that the divide between the young and old will worsen as the population ages, and the self-interest of the older generation will ensure that the status quo continues. However, this misses the key point: the age at which the intergenerational divide begins is not constant. It is likely that this age will increase over time as those left behind are unable to catch up and thus the average age of discontentment with the status quo continues to increase over time.

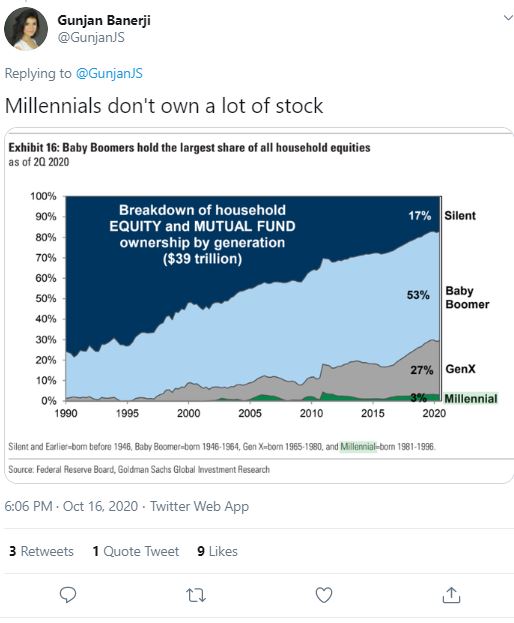

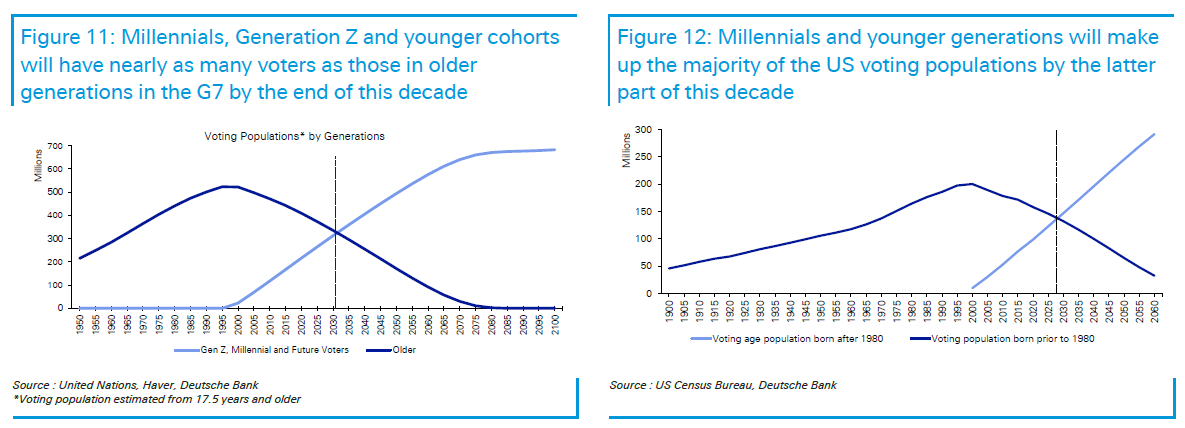

The Millennial generation (born in the early 1980s), along with Generation Z and younger voting cohorts, are firmly established as generational ‘have nots’. Yet in G7 countries, the combined size of these groups is fast catching up to that of the generations born prior to the Millennials. The two groups on either side of the divide will be close to neck-and-neck by the end of this decade in aggregate and slightly earlier in the US.

ZEROHEDGE DIRECTLY TO YOUR INBOX

Receive a daily recap featuring a curated list of must-read stories.

Assuming life does not become more economically favourable for Millennials as they age (many find house prices increasingly out of reach), this could be a potential turning point for society and start to change election results and thus change policy. This is particularly the case when we recognise that the votes for Brexit and Trump in 2016 left many younger people feeling angry and alienated by political decisions that a sizable majority of them were against.

Such a shift in the balance of power could include a harsher inheritance tax regime, less income protection for pensioners, more property taxes, along with greater income and corporates taxes already mentioned, and all-round more redistributive policies. The “new” generation might also be more tolerant of inflation insofar as it will erode the debt burden they are inheriting and put the pain on bond holders, which tend to have an ownership bias towards the pensioner generation and the more wealthy. The older generation may also have to be content with lower (or even negative) asset price growth if the younger generation does not have a sudden income boost.

Whether or not individuals see the above as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is not necessarily the point. Rather, it seems clear that this will be a big break from the status quo and lead to far more disorder than in the prior era of globalisation.

Amidst the clash between the young and old, an increasingly fraught issue will be climate change – something that increased during and because of the recent globalisation era. This is our seventh key theme and is one where heavily polarised opinions exist – not just about the extent of the problem, but around the various options available to respond. Although the pandemic has displaced climate change from the front pages for now, as the size of the pro-climate younger generation grows, so too will the pressure on leaders to act.

We are likely to see huge pressures for a greener response to the post-pandemic economic rebuild. To move the world to a consumption-driven model of measuring and judging carbon emissions, we believe a carbon border adjustment tax is needed and this will likely be implemented this decade. Given more Millennials will be elected into positions of power over the coming decade, this tax will probably not suffer from the same watering-down as other environmental legislation. As such, a strong carbon border tax will reinforce the disruption to the status quo and create disorder for both companies and countries in terms of the relationships between them that in the era of globalisation were relatively calm.