Making sense out of Chaos

Remya Nair and Moushumi Das Gupta 23 July, 2020 8:24 pm IST

ext Size: A- A+

New Delhi: The government is set to push spending by infrastructure ministries this year as it looks to revive economic growth and boost job creation.

The finance ministry has reached out to major infrastructure ministries like railways and roads and highways, asking them to step up spending to meet budgeted expenditures, two government officials confirmed.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent increase in expenditures and contraction in tax revenues forced the finance ministry to place expenditure curbs on many government departments. Ministries like health and family welfare, rural development, textiles and food and consumer affairs were some of the exceptions — they were allowed to spend freely as required. But infrastructure ministries like railways, housing and road transport and highways were allowed to spend only up to 40 per cent of the full year budgeted amounts in the first half of the fiscal.

However, with the pandemic, and the consequent lockdown and disruption in economic activity, leading to a sharp growth contraction in the first quarter of 2020-21, the government is keen to revive spending by infrastructure ministries.

Economists expect the Indian economy to contract between 5-12 per cent in 2020-21, but rebound in 2021-22.

Speaking at a FICCI event Thursday, Department of Economic Affairs Secretary Tarun Bajaj said the government could borrow “a little more” if needed to fund infrastructure spending.

My view

The multiplier impact of infrastructure spending is huge. S& P global writes “We believe, for India, investments in infrastructure equal to 1% of GDP will result in GDP growth of at least 2% as infrastructure has a “multiplier effect” on economic growth across sectors.”

July 21, 2020

It may or may not happen at next week’s FOMC, but that hardly matters. What’s important is that a policy shift is coming and the impact upon the precious metals will be significant.

Many times already in 2020, we’ve utilized this space to explain why negative real interest rates are the most extraordinarily important and fundamental rationale for owning physical gold and silver. Most recently, this article from two weeks ago:

• https://www.sprottmoney.com/Blog/real-rates-drive-…

As we head toward another Federal Open Market Committee meeting next week, attention will turn again to whether or not the FOMC will soon implement a policy of “Yield Curve Control”. In the days leading up to last month’s FOMC meeting, this notion was all the rage, but while Yield Curve Control was discussed at the meeting, no formal announcement was made.

• https://www.bondbuyer.com/news/how-yield-curve-con…

Which is interesting, as it appears that some measure of “de facto” yield curve control has already been put into place, beginning around April 1 of this year and with an easily-identifiable range between 60 and 75 basis points.

Whether or not this policy is already being covertly applied hardly matters. Instead, it’s clear that The Fed is headed in this direction and the impact across all markets will be significant.

Late last week, a trial balloon was floated by Bloomberg. You may have missed it, but if you’re a gold and silver investor, it’s extremely important that you take time to consider it today. Here’s the link:

• https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-07…

What is this “major policy change” that Bloomberg reports The Fed is actively considering? In a move away from their oft-stated “dual mandate”, The Fed is preparing to change their policy to allow for an overshoot of inflation, above and beyond the current goal of 2% per year. Will this policy change be announced next week? Maybe. Will it be announced in September? More likely. Will it be announced before year end? Almost definitely.

And with this policy shift will come the necessity of Yield Curve Control. Why would YCC become indispensable? Because without it, a rising inflation rate would force interest rates higher…and The Fed is on record stating that they plan to hold yields near zero through 2022. The article from Bloomberg concludes as much, as you can see from the closing paragraph:

Articles such as this don’t appear at Bloomberg by magic. Instead, these trial balloons are designed to measure market response in advance. So understand that higher inflation targets AND yield curve control are very likely coming before the end of the year…and perhaps as soon as September or even next week.

And what does this mean for gold and silver investors? It’s an institutionalization of sharply negative real interest rates. If The Fed holds the yield on the 10-year note below 1% while inflation moves toward 3% or 4%, then negative inflation-adjusted returns for this bedrock institutional holding will drive demand for gold as an alternative Tier One asset. Already, traditional mainstream analysis is beginning to understand the ultimate impact on gold prices. See this from Barron’s:

• https://www.barrons.com/articles/gold-could-overta…

In conclusion you, too, must also recognize the hugely significant implications that this impending “policy shift” will have on the precious metals. The year 2020 has already seen some tremendous gains for gold and silver. However, when The Fed announces the policy changes of higher inflation and yield curve control, the current price rally is likely to accelerate to the upside.

About Sprott Money

Specializing in the sale of bullion, bullion storage and precious metals registered investments, there’s a reason Sprott Money is called “The Most Trusted Name in Precious Metals”.

Since 2008, our customers have trusted us to provide guidance, education, and superior customer service as we help build their holdings in precious metals—no matter the size of the portfolio. Chairman, Eric Sprott, and President, Larisa Sprott, are proud to head up one of the most well-known and reputable precious metal firms in North America. Learn more about Sprott Money.

@jturek18, jonturek@gmail.com

The one trade now in global macro is, can policymakers continue to get whatever outcomes they want.

Sections: – For the market, skew has mattered more than expectations

– Macro in a world of policy omnipotence

– The last idiosyncratic rates trade, China

– Is the JGB curve ironically the best DM steepener

For the market, skew has mattered more than expectations One of the things that has seemingly been missed in this market is, the narrative has been focused on outcomes while the market has been pricing skew. I think over the past few months there have been a few examples of this.

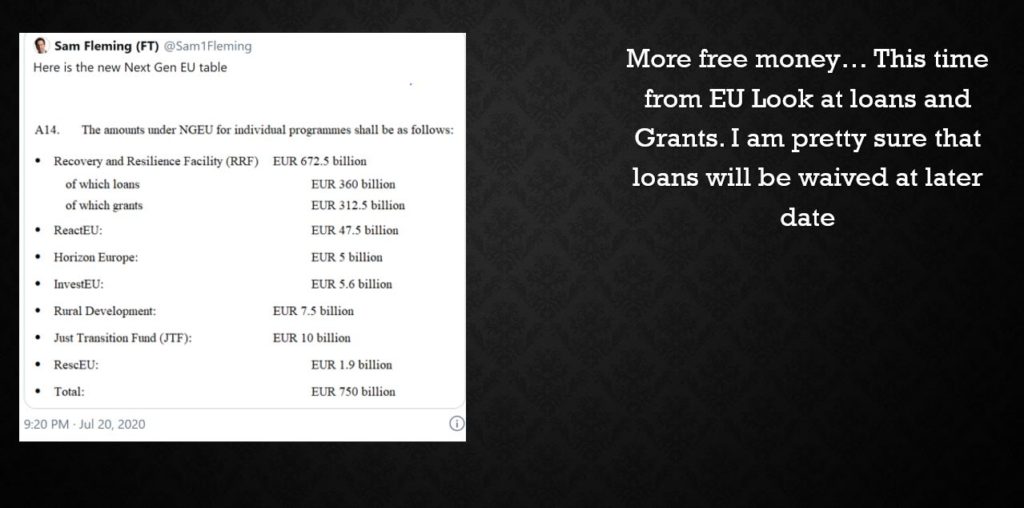

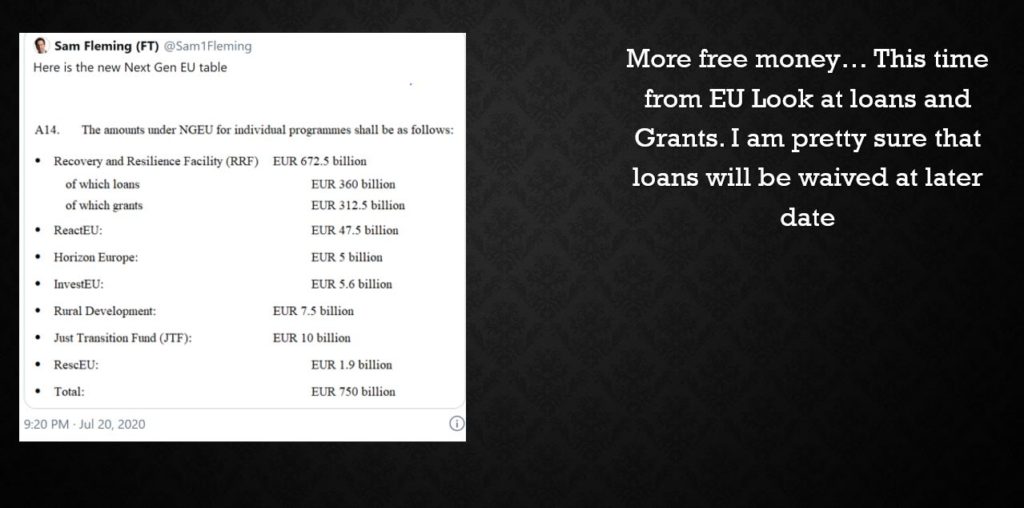

– EUCO recovery fund. The narrative at the beginning of the process after the M&M press conference on May 18th, the size is not big enough. What has the market reaction been? the precedent of European fiscal transfers is a far more important development than the actual size of the recovery fund. As we have learned in Europe, it is harder to start something than to make it bigger, ask Mario Draghi.

– In the US, fiscal stimulus was supposed to struggle to cap the revenue drop caused by the unprecedented nature of this crisis. To an extent, it has, but what this narrative missed in a distributional sense is, the policy response to deflationary shocks has changed and the left tail has been clipped. The government sends out money and the central bank does open ended QE. Does this mean future growth is promised, no, but it does change the recession landscape in terms of size and duration.

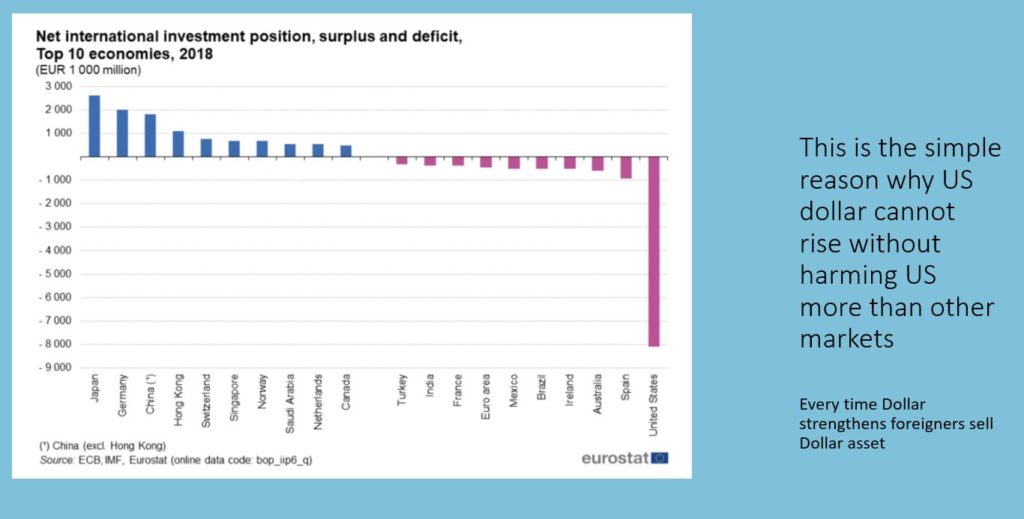

– The US dollar is another example of this. How was the Fed going to downstream dollars to EM corps and Asian non banks. And then from there, was there really going to be a change in global growth composition that would change the USD “smile” world where US asset outperformance continues in perpetuity. Would previously frugal surplus countries step up with ambitious fiscal plans that would not only plug the covid hole but transcend the current crisis and serve as an economic accelerant going forward. The immediate answer to a lot of these questions was, the most probable outcome is no, but the market traded the skew and thats where we are today.

Going forward, I’m not sure what changes the current risk dynamic. I think a very interesting dynamic has been the fact that a weak dollar has not elicited a response from the long end of the US bond market. This may speak to the asymmetry we see in the current relationship. When the dollar is strong it weighs on global NGDP and thus term premium. When the dollar is weaker, FX basis tightens, and it again makes sense for foreign real money to buy the long end FX hedged to get a yield pickup over its local government bond equivalent. This latter dynamic is like rocket fuel for risk assets, especially EM, as all the stimulative effects of a weaker dollar, trade finance etc. can happen without a commensurate move up in term premium. This is the dream for EM. The question now is, after a pretty substantial move lower in the dollar, does it make sense to have some tactical stuff against core positions that have a risk bias. I think the places to look for this sort of exposure is CBs that have already said they don’t want further FX appreciation (ILS, THB, TWD).

Macro in a world of policy omnipotence One of the more amazing transitions in markets since March has been the market’s outlook towards policy. In the darker days of March, the Fed was “constrained” by the effective lower bound and fiscal was too slow. So the bet was, this shock would overwhelm policy. Fast forward to now, and the market has basically said no shock is too big for policy makers and if that is the case, we just gravitate towards the right side of the risk distribution as the policy put is struck so high.

Where we are now is, the market asks itself what the Fed wants and then puts those trades on. What are those trade:

– The Fed wants a weaker dollar. They turned every world government bond market into USD to prove that.

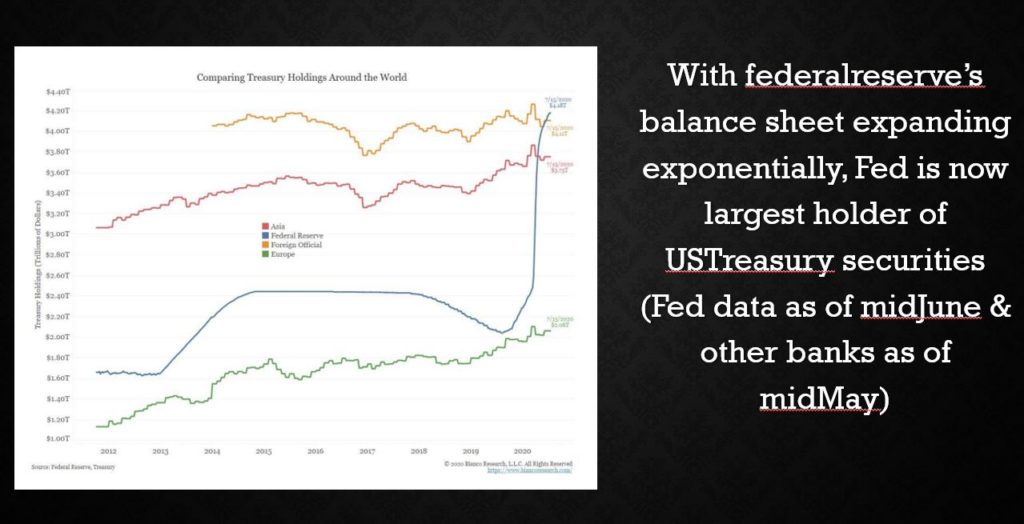

– The Fed wants IG to trade at new tights. Allowed record IG issuance three months in a row. Liquidity that prevents solvency issues.

– The Fed wants risk assets higher to ensure smooth financial market functioning for the real economy.

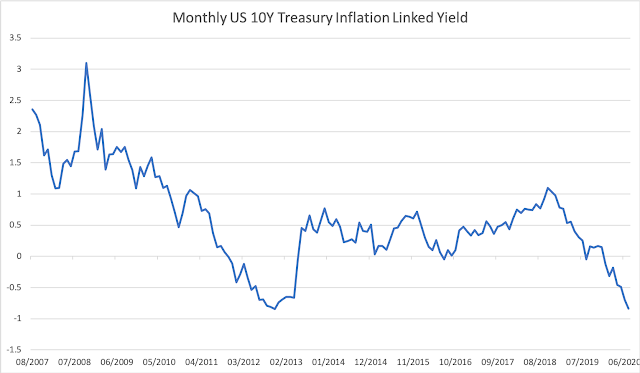

– The Fed wants real yields to plummet which effectively allows their easing footprint to expand with improvements in the outlook. Pro cyclical policy.

We are now in the market cycle of, the Fed can do what it wants, so the only thing to figure is what it wants to do.

The next stage of this understanding is in Brainard’s speech from last week. The theme of that speech was the transition from “stabilization to accommodation”. But I will translate that differently: we got nominal yields where we want them, now the policy focus is on real yields.

A key theme in the speech was this transition of, “stabilization to accommodation.” What does that look like. Well, we know from pre covid, at the ZLB, Brainard was in favor of using ycc to reinforce forward guidance. However, “stabilization to accommodation” has further consequences. This theme of transition is right out of the Benoit Coeure playbook. During the stabilization period, what is important, as Coeure put it, is for the central bank to “put its money where its mouth is.” QE plays outsized role and has a higher multiplier. Then the transition happens, to accommodation. QE multiplier falls as policy has succeeded in shifting upwards the distribution of risks around the growth outlook. This is when strong odyssean or outcome based forward guidance is most efficacious and asset purchases serve as reinforcement for forward guidance. “As the outlook improves, the signal that asset purchases send regarding the likely date of a first rate hike becomes increasingly important for anchoring the medium to long-term segment of the curve.” This is where the Fed is: they have cutoff the mechanism in which good news is priced into any part of the yield curve and they plan on reinforcing that, whether that is outcome based forward guidance with curve caps or not, I’m not sure it will matter. The market already knows. The Fed’s policy goal is to prevent bad things and accentuate good things.

So the skew for real yields is still towards going further negative. A few things:

– The market has transitioned from thinking policy can’t respond to this size of a shock, to where it is now, policy can do anything. Betting on rising real yields is basically a bet policy is outmatched versus the size of the shock. That has been the wrong bet.

– Assuming my previous note about the dollar being a solved problem is in the ballpark, the chances of a runaway dollar clogging up the financial plumbing and constricting trade finance again has been severely reduced.

– The traditional Phillips Curve is dead. Maybe the New Keynesians have it right (marginal cost driven as opposed to slack). In fairness, they did tell us to look through current slack. Future marginal costs matter more than current economic activity. I.e. there is this form of discounting which leads to stickiness. But either way, in a world that policy makers are going to be expected to replace lost incomes, the distribution of potential economic outcomes is changed.

One of the things that weighed so heavily on bonds and breakevens in the prior decade was the asymmetry of deflation. When the economy was doing well, inflation did nothing, so imagine what would happen in a recession. That skew has fundamentally changed in a world where lost income is replaced to a certain extent and recoveries are unencumbered by premature stimulus withdrawals.

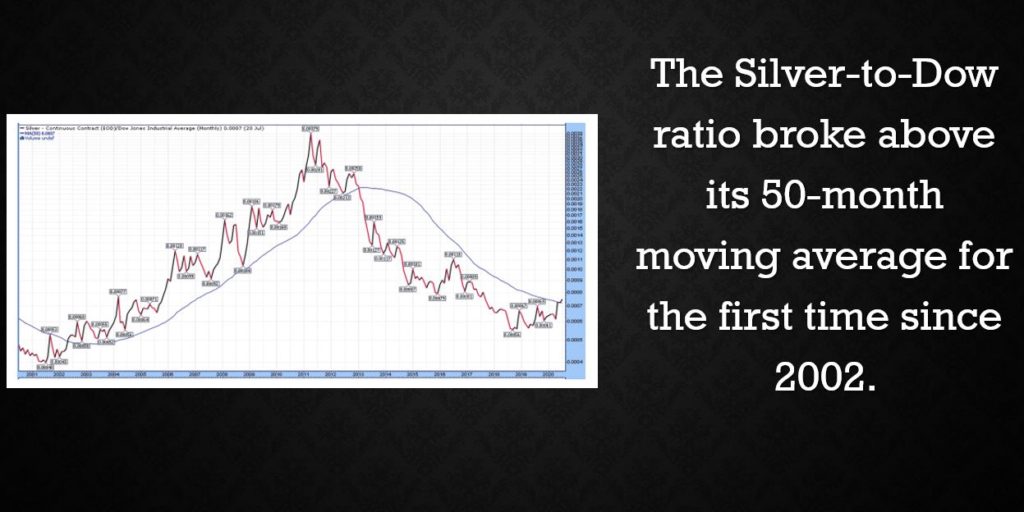

I’m not sure what stops this chart unless the market is to reevaluate its views on USD. Real yields and precious metals by extension are a just bet on continued policy omnipotence.

The last idiosyncratic rates trade, China

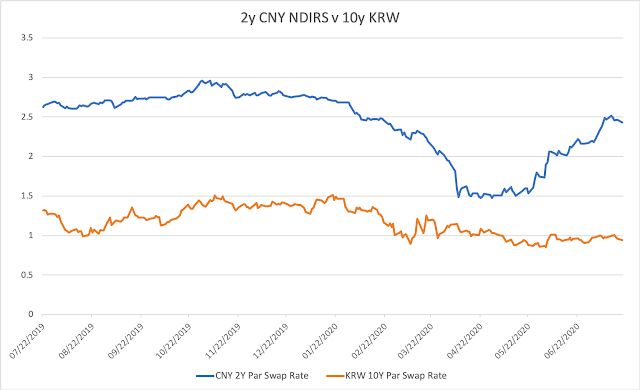

One of the more interesting and frustrating government bond markets in the world has been China. Yields in China seem to be the only place where the market is taking the “V” seriously. And when it comes to things like TSF (total social financing) and industrial production in China, it has been pretty “V” like. To add to this, China following the NPC let rip a special CGB issuance which the NPC fast tracked. Without a big RRR cut and other liquidity measures from the PBoC which were evidently absent, it zapped all the liquidity from the market and yields backed up a lot and the fixing rate from 1.5% to over 2.2%.

The question now is, are Chinese rates the place to receive and get some counter risk exposure. I have been burned on this trade before, but in terms of asymmetry, it ticks all the boxes. The Chinese “V” in industrial activity is more than priced and TSF numbers have likely made policy makers a bit nervous which could see the Q3 numbers come down. And finally, the PBoC is now adding a lot of liquidity even if it is not cutting rates such as the MLF or OMO. Since last week, the net injection of reverse repos has been over 230b RMB. To me, at a minimum this is policy makers saying, rates have gone far enough. And if that is the case, you get some negative equity correlation with a good risk reward.

A trade I am really interested in is a cross currency steepener with Korea. Basically the idea is, if Chinese industrial activity is again leading the global economy out of covid, then the backend of Korea should begin to reflect that. So if this is a China led reflation, 10y KRW below 1% is probably wrong. On the flip side, in risk off, Chinese 2y above the fixing rate will move a lot. The point of this trade is, you are vol-adjusted received, and in case reflation goes into third gear, you’re paid some duration and hoping the front end of China still sticks towards the fixing.

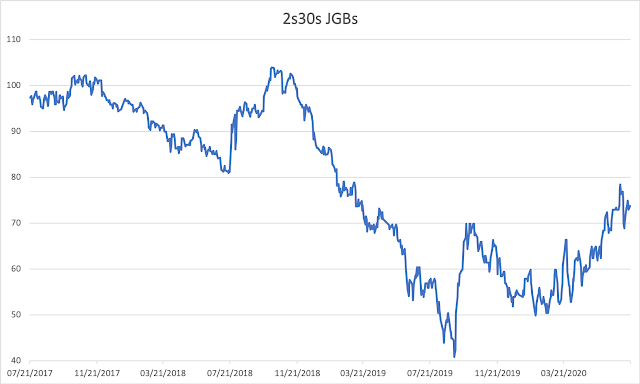

Is the JGB curve ironically the best DM steepener?

Not so many people spend much time on JGBs anymore, and probably for good reason, it’s barely a market at this point. With that said, there seem to be a few interesting parts to the market, especially given the external backdrop.

Going back at least a year, in the very front end (tbills) and the very long end, there has been a lot of interesting things going in JGBs, even if YCC has crushed everything in between

– In the long end, the BoJ has not been shy about encouraging steepness in the name of financial stability. This has been clear in FSR’s (financial system report) and Rinban schedules of long end purchases. The BoJ is firmly aware that too flat of a curve is a problem for its bank/saving heavy economy. Throw on covid and budget blowout after at least two supplementary budgets, it makes sense the curve has steepened quite a lot, especially in the back end.

– In the short end, something else has been going on over the past couple years ago and it explains why foreign ownership of JGBs has soared. Basically, as Japan was one of the biggest users in the FX swap market in terms of funding/hedging USD, its cross currency basis swap spread traded very negative. Because of this dynamic, money would come into the FX swap market to take advantage of this very negative spread. What happens is, money comes in to take the other side of Japanese lifer/pension money looking for USD, usually at 3m point. Lifers would swap Yen for USD, to either US banks or reserve managers sitting on USD. Now, with all that Yen, these players would then buy Japanese tbills, which because of the negative xccy created a massive yield pickup over equivalent treasuries or bunds. However, given where FX basis trades now, the Japanese carry trade is a bit less compelling.

This dynamic could set Japan up to actually be the most asymmetric steepener out there. What we have seen so far is, as it relates to DM curves is, anything with carry and rolldown gets taken in, which explains the foreign bid in ACGBs. However, the background of that is, if FX basis is normalized, Japan can go back to getting foreign hedged yield pickup abroad, which will weigh on the long end in JGBs. Basically the point of this is, 2s30s Japan is being encouraged to steepen by both policy makers and dynamics within the financial plumbing. It can’t go forever, but Japan may ironically be the place to steepen.

Japan more so than anyone else explicitly wants steepness in the curve and some of the technical backdrops may go to reinforce that bias. Of course there will be cuteness with overseas buying of JGBs on asset swap to take advantage, but the bias of the long end of the curve is to steepen and Kuroda wants the same thing.

Martin Armstrong writes on his blog

We have reached the point of no return. Governments will find it IMPOSSIBLE to constantly roll their national debts as we enter 2021. Any attempt at paying down the public debt or moving into surplus would be catastrophic and undermine the entire world economy. Who are we kidding? The tax burden on each generation will progressively get worse until we see blood in the streets, which seems to be the only solution to corrupt governments.

This immediate health crisis has been really been the covert means of forcing the climate change agenda to alter the economy trying an elitist view to recast our fate. There are those who now advocate Modern Monetary Theory as the ONLY way out and point to six years of negative interest rates in Europe since 2014 with excessive creation of money the resulted in deflation.

Their view of neoliberalism supported by Keynesian Economics has collapsed. Therefore, the solution is to cancel all physical money, eliminate cryptocurrencies, and force their vision of how to create this New Green World Order/Great Reset that they claim will produce FULL EMPLOYMENT, which is simply just another empty promise constructed upon theory rather than reality.

by Kuppy via adventures in capitalism

here is a head-scratcher;

-On one side, we have wave 2 of COVID-19, complete with new restrictions in multiple counties and states. Roughly 30 million people are out of work. Thousands of businesses are failing each week due to government COVID-19 mandates. Rent and mortgage payments are increasingly delinquent and all of this is before the fiscal stimulus tapers off.

-On the other side, the Nasdaq is at new all-time highs and the S&P 500 isn’t far behind.

Isn’t the market supposed to be correlated to the overall economy? Otherwise, this would be the greatest spread yet between reality and fantasy during the “everything bubble.”

I’ve taken to calling the current government actions “Project Zimbabwe” as we are following the same failed monetary policies that Zimbabwe used. Oddly, despite no electricity, running water or food, much less a functioning economy, the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange index went up violently for years straight—it frequently doubled in a single day. Why? Because that was the rate of money printing and inflation. As the US economy embarks on a similar (but hopefully more subdued) policy path, we’ll also experience a similar reaction in our markets.

But what about the collapsing economy? How can the market be at highs while things are so awful? I played around with my Bloomberg and built the chart below.

The top panel should be pretty self-explanatory. In white, we see the S&P 500 ETF (SPY – USA) over the past decade and in yellow we can see the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet over the same time-span. In the lower panel, we’re going to analyze the ratio of the two. Coming out of the GFC, we had a bounce in the first year, a shake-out during the European debt crisis and then a narrow trading range as the S&P and Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expanded at a constant pace. Then, following Trump’s election victory, the S&P gained some real steam as taxes were reduced, regulations removed and the President tweeted everyone into the market. So far, the lower panel makes logical sense. What I find stunning is that after the COVID-19 crash, we’ve barely even bounced off the lows. In fact, we gave back a decade of retained earnings, financial engineering and everything else. We’re actually all the way back at 2010 levels. That’s stunning right? It’s literally been a wasted decade in the financial markets when indexed to the Fed’s balance sheet. That’s your COVID-19 crash and it’s as severe as you’d expect it to be.

Anyone who’s telling you that they do not understand the stock market making new highs while the economy is broken isn’t looking at the market when indexed to the Fed’s balance sheet. They’re not thinking of the radical implications of “Project Zimbabwe.” It simply makes my head hurt that there are investors out there who are shorting equities with a structural view that the economy is a mess. Your only logical exposures are long and very long. There will be a whole lot of volatility along the way (especially during those short periods where the Federal Reserve shrinks their balance sheet), but as long as the government has us on the “Project Zimbabwe” path, the market is going much higher in US Dollar terms. I want to be riding that freight train, not shorting the occasional violent contra-trend moves. Besides, based on the chart above, we actually have some ground to make up as I refuse to believe the past decade was completely wasted.

Michael Avery from Rabobank has written a report on “MMT”

Summary

The COVID-19 crisis has, as expected, seen moves towards Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to deal with soaring public deficits and debt

MMT states that governments only face inflation limits to money printing: while inflation is low for now, it won’t stay that way forever

Only eight countries in the world meet our proposed MMT criteria: leaving aside the US,these countries need the rare combination of sovereign currency, simultaneous fiscal deficitand current account surplus, plus good governance

As such, MMT may be a very strong medicine but, in almost all instances the cure is likely worse than the disease – a fact that will increase geopolitical stresses ahead

Looking at the specific example of India, we show that a major MMT fiscal package could push inflation up to 12% and the currency down by 25%

When I talked about “INFLATION” few days back I could sense that I was not able to answer some questions to your satisfaction and possibly I myself did not have those answers. Russell Napier gave this interview over weekend where he clarified the path over next couple of years.

Finally it boils down to velocity of money and I will give some headlines over the weekend.

The Canadian government wants to expand the emergency wage subsidy programme so that all businesses suffering losses from the virus will benefit, Finance Minister Bill Morneau said.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has said that he is considering “forgiving all small (PPP) loans”. As of now, the government has approved USD518.1bn of loans spread over 4.9m PPP loans. He did not specify what “small” would constitute.

After 3 days, EU leaders have so far failed to come to any agreement on a bailout package, however negotiations will resume this afternoon and Bloomberg says that the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden are prepared to accept EUR390bn of the fund being made available as grants with the rest coming as low interest loans.

The Australian Treasury will extend its loan guarantee scheme for small businesses and increase the credit limit up to AUD1m from AUD250,000, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said.

INTERVIEW below https://themarket.ch/interview/die-zentralbanken-sind-irrelevant-geworden-ld.2327

Market watcher Russell Napier warns that investors should prepare for inflation rates of 4% and more in the coming year. Governments have taken control of the money supply.

In the years following the financial crisis, numerous economists and market observers have warned of rising inflation rates given the central banks’ expansionary monetary policy. They were always wrong.

Russell Napier was never one of them. The Scottish market strategist has correctly viewed disinflation as the dominant issue for financial markets for two decades. For this reason, investors should listen to him when he warns of rising inflation rates.

“Politicians have gained control over monetary control, and they will no longer give up this tool,” said Napier. For him, we are at the beginning of a new era of financial repression in which governments are ensuring that inflation rates remain consistently above interest rates for years. This is the only way to reduce horrendous debt.

In the interview, Napier says how investors can protect themselves and why central banks have lost their power.

Mr. Napier, for over two decades you have written that investors should be prepared for deflation. Now you warn that we are at risk of inflation. Why and why now?

The reason is the way money is created today. Most investors only look at the tight monetary aggregate and the size of the central bank balance sheets. But the broad money supply is much more important. This has grown very slowly over the past 30 years. That was, along with China’s integration into the world trading system, a main reason for low inflation.

And has that changed now?

Yes, fundamental. We are currently experiencing the worst recession since World War II, and yet we are seeing the fastest growth in the broad money supply in at least three decades. In the United States, M2, the widest aggregate available, is currently growing at an annual rate of over 23%. You have to go back at least to the time of the civil war to find comparable strong growth. In the eurozone, M3 rose 8.9% in June. It is only a matter of months before the previous record level of 11.5% from 2007 is leveled out.

Why is that relevant?

The big question is: Does the growth of the broad money supply matter? Investors are obviously not of this opinion because the breakeven rates of inflation-linked bonds are extremely low. The market therefore sees no relevance in the current growth of M2. He is probably only considering this as a short-term exception due to the Covid 19 shock. But I think it matters. The key point is knowing who is responsible for this money creation.

Who then?

The broad monetary growth is created by government intervention in the commercial banking system. Governments provide guarantees to banks to lend to businesses. This is money creation in a way that completely bypasses central banks. I am therefore convinced that this money supply growth will lead to inflation. More importantly, the money supply will no longer be controlled by the central banks, but by the governments – and thus by politicians. Politicians have different goals than central bankers. You need inflation to get rid of the high debt. Now they have the mechanism to create inflation.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, central banks began quantitative easing policies. They tried with all their might to create inflation – without success.

The QE policy was a fiasco. Everything central banks have created over the past decade is a large amount of debt outside the banking system. QE kept interest rates low, driving up asset prices and allowing companies to get cheap debt by issuing bonds. Instead of growth of the broad money supply and higher nominal economic growth, they have only provoked high debt growth. We have to understand that most of the money is not created by central banks, but by commercial banks. After the financial crisis, central banks never managed to get commercial banks to lend and create money.

If central banks failed to increase nominal GDP growth, why should governments succeed?

By exercising control over the commercial banking system, governments can bring money to those parts of the economy that central banks can never penetrate. Politicians give credit guarantees and the banks are happy to answer the call, of course. They are now issuing the loans that they have never granted in the past ten years.

Are not the state credit guarantees just a one-off measure to combat the economic impact of the pandemic?

Politicians will recognize that they have a powerful tool in their hands. We saw a fine example two weeks ago: the Spanish government has increased its bank guarantee program from € 100 billion to € 150 billion. Just because. There will be a gradual expansion of measures, for example to finance green investment programs. In addition, these loans often have a term of several years. The credit pulse is already in the system.

In the years since the financial crisis, central banks have never been able to persuade commercial banks to lend. So governments are taking power and they won’t let go of this instrument?

Exactly. Even before Covid-19, debt to GDP was far too high in most industrialized countries. We know that debt must go down. For politicians, inflation is always the cheapest way out of this mess. Thanks to the Covid crisis, they have found a way to take control of the money supply and generate inflation. A credit guarantee is not a fiscal expenditure, it does not appear to burden the state budget, since it is only a contingent liability. So if you are an elected politician, you have a cheap way to fund the economic recovery. Politically speaking, it’s incredibly powerful.

A magical source of finance?

Yes. Theresa May made a speech a few years ago saying that there is no magic tree on which money grows. Well we found him. As an economic historian and investor, I know that this policy will be a disaster in the long run, but in the eyes of a politician, this is the magic money tree.

A prerequisite for this miraculous source of money is that governments keep control of their commercial banking system, don’t they?

Correctly. In 2016 I wrote a study entitled “Capital management in the age of financial repression”. In it I wrote that the final step in the next financial repression would be triggered by the next crisis. So Covid-19 is just the trigger for the start of an aggressive financial repression.

Do you expect a repeat of the era of financial repression that marked the decades after World War II?

Yes. At that time, numerous governments used financial repression tools that were only abolished in the 1980s. They also used it to overcome a financial emergency; this emergency was called World War II. It is often an emergency that gives governments extreme powers. Again, the debt-to-GDP ratio was way too high before Covid-19. Our governments know that this debt needs to be reduced.

And the best way to do that is financial repression by making nominal GDP grow faster than debt?

This is what we learned after World War II: higher nominal GDP growth thanks to higher inflation rates works wonders to lower debt to GDP.

Which countries will choose this path in the coming years?

The entire developed world: the USA, Great Britain, Europe, Japan. I see only a few exceptions, such as Switzerland and Singapore. If Germany and Austria were not part of the euro zone, they would not have to do any repression. Of course there is a catch: if the Swiss do not become financially repressive, a great deal of escape money will flow into the Francs.

So there will be more upward pressure on the Swiss franc?

With certainty. Financial repression will also lead to capital controls. Switzerland will have to adopt capital controls to ward off money, while other countries will implement capital controls to prevent money from flowing away.

The cornerstones of the period of financial repression from World War I to the early 1980s were capital controls and the compulsion for domestic financial institutions to buy domestic government bonds. Do you expect these two measures to be reintroduced?

Yes. Domestic savings institutions such as pension funds can easily be forced to buy domestic government bonds at low interest rates.

But can capital controls really be implemented in today’s financial world?

For sure. There are two countries in the euro area that have had capital controls in recent history: Greece and Cyprus. Iceland introduced capital controls after the financial crisis, which many emerging markets are using. If you can successfully implement them in two members of the European Monetary Union, you can implement them anywhere.

When do you expect inflation to rise?

I see 4% inflation in the U.S. and most industrialized countries by 2021. My expectation is primarily based on a normalization of the speed of money. This is currently likely to be around 0.8 in the United States. The lowest prior value was 1.4 in December 2019, at the end of a multi-year downward trend. QE has been an important factor in declining orbital velocity, as central bank liquidity poured into the financial system but never reached the real economy.

What will increase the speed of circulation again?

The money that the banks are distributing today thanks to the state guarantee goes directly to companies and consumers. They are not currently spending it, but with a normalization of the economy, the money will come into circulation. I think the speed of circulation will increase to around 1.4 again next year. Given the monetary expansion we have already seen, this would quickly result in an inflation rate of 4%. There is another factor, China: For the past three decades, China has been a source of deflation. But we are at the beginning of a new Cold War with China, which will mean higher prices for many goods.

The yield on ten-year US government bonds is currently around 0.6%. What will happen to the bond market when investors realize that we are heading for an inflationary world?

Bond yields will rise sharply. This is because the markets are beginning to realize that politicians are now controlling the money supply. That will cause a shock.

For successful financial repression, governments and central banks must keep bond yields below the inflation rate. How does that work?

Governments will force their austerity institutions to buy government bonds to keep yields low. The central banks will be unable to do anything to limit the rise in bond yields.

Why not? Even the US Federal Reserve is playing with the idea of yield curve control, an instrument it used between 1942 and 1951 to cap ten-year interest rates at 2.5%.

This is an inappropriate parallel, because back then there was rationing, price and credit controls. This made it easy for the Fed to limit bond yields. Yield curve control is easy when everyone expects deflation, as the current example from the Bank of Japan shows. But once market participants start to seriously expect inflation, they will want to sell their bonds. It is then hardly possible for the central bank to control the yield curve.

They say that politicians are now controlling the money supply. Then what will the future role of central banks be?

They are marginalized and primarily focus on regulatory rather than monetary policy tasks. The next few years will be fascinating: imagine you and I run a central bank and we have an inflation target of 2%. Now we have to see how our government creates money with a growth rate of 12%. What we gonna do? Will we attack our democratically elected government and threaten higher interest rates?

Paul Volcker did it in the early 1980s.

Yes, but Paul Volcker was brave. I don’t think any of today’s central bankers will have the courage. Ultimately, governments will argue that there is still an emergency. I see a parallel to the 1960s when the Fed took no action against rising inflation because the United States was waging a war in Vietnam and the Lyndon B. Johnson government had launched the Great Society Project to reduce inequality in America. With this in mind, the Fed did not have the courage to pursue a tighter monetary policy. Today we are back to this point.

So central banks will become irrelevant?

Yes. That’s an irony of fate: most investors believe in the unlimited power of today’s central banks. In fact, their power is as low as 1977.

How should you adjust to your inflation scenario as an investor?

Under no circumstances should you buy government bonds. By contrast, inflation-linked bonds in Europe are attractive because they price in low inflation rates. Gold is a long-term, first-class asset. Equities are also likely to perform well over the next few years. Slightly more inflation and higher nominal growth create a good environment for the stock exchanges. Historically, inflation rates above 4% were no longer good for stocks. I currently particularly like Japanese stocks. With the perspective of financial repression, however, there is an aggravating factor: as soon as governments force their savings institutions to buy government bonds, they will have to sell something. And that will be stocks.

How high will inflation rise?

If we look at the next ten years, I see inflation rates between 4 and 8%. Over a period of several years and in conjunction with low interest rates, this will be enormously effective in reducing debt to GDP.

What does an investor need to move successfully in the markets in the coming years?

First of all, we have to recognize that we are dealing with a long-term phenomenon. I’m talking about decades, not years. Everyone is so busy with the current crisis that they don’t see long-term change. The financial system has changed fundamentally. It has become a very dangerous place for savers. Many skills that we have learned over the past 40 years are superfluous because we have been through a long period of disinflation. It was a time when markets became more important and governments became less important. Now the wind has changed. Those who have dealt with emerging markets for a long time will have an advantage. Investors in emerging markets know how to deal with higher inflation rates, government intervention and capital controls. That will be our future.

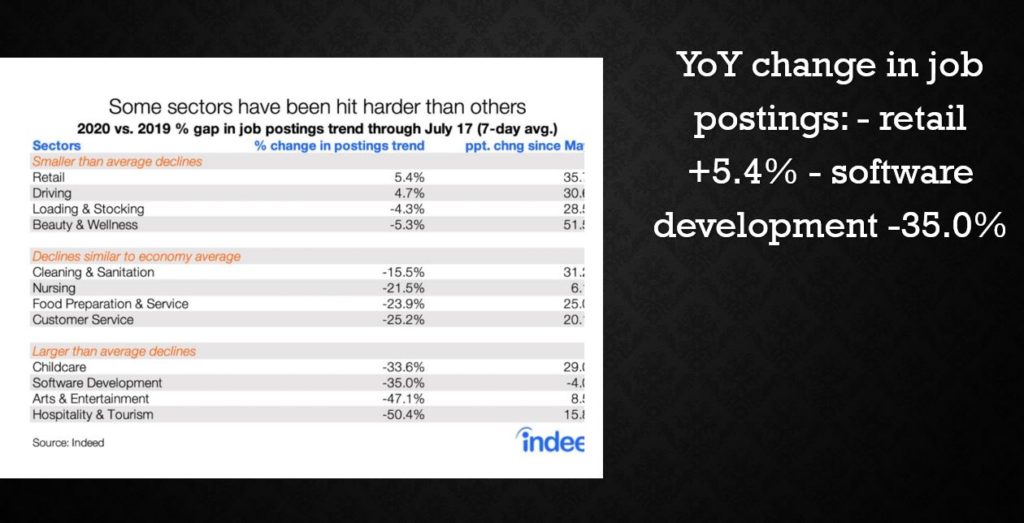

In many respects this recession is unique. Most recessions result from developments inside the economy, but an external shock—the public health crisis—caused this one. To avoid getting sick, people have curtailed working, shopping, and attending school. Whatever the cause, the coronavirus recession, like all recessions, is imposing heavy costs. Many workers have lost jobs and income, and many business owners’ financial survival is at risk. The economy’s extraordinarily rapid decline earlier this year—as well as the sharp but incomplete rebound following the first steps toward reopening—reflect this recession’s unusual source. In addition, the sectors suffering most differ from past recessions. The heaviest blows have fallen on service industries that involve close personal contact (including retail trade, leisure and hospitality, and transportation) rather than, as is more typical, on the housing, capital investment, and durable goods sectors. Lower-paid workers, as well as women and minorities, are over-represented in the most-affected sectors, and thus have borne a disproportionate share of the job and income losses. And, the virus has affected almost every country, with potentially devastating consequences for trade and international investment.

Because this recession is unprecedented in so many ways, forecasting the recovery is difficult. The course of the pandemic itself is by far the most important factor. As long as people fear catching a potentially deadly illness from other people, they will be cautious about resuming normal activities, even after state and local governments lift lockdowns. Thus, controlling the spread of the virus must be the first priority for restoring more-normal levels of economic activity—but, more importantly, for saving possibly tens of thousands of lives. Members of Congress, local leaders, and other policymakers need to do all they can to support testing and contact tracing, medical research, and sufficient hospital capacity, and they must work to ensure that businesses, schools, and public transportation have what they need to operate safely. Both authors of this testimony are serving on state re-opening commissions, which has provided us insight into the substantial challenges to safe re-opening.

If the pandemic comes under better control, economic recovery should follow. However, the pace of the recovery could be slow and uneven, for several reasons. First, in the face of ongoing uncertainty, households and businesses may remain cautious for a time. They may increase saving and reduce spending, hiring, and capital investment. The longer the recession lasts, the greater the damage it will inflict on household and business balance sheets and the longer it will take to repair the damage. Second, the depth of the recession may leave scars—business closures and the deterioration of unemployed workers’ skills—that will affect growth for several years. Third, depending on the course of the virus, some restructuring of the economy may be needed. For example, people and resources will need to be redeployed out of the sectors most damaged by the pandemic, and business operations will need to be reorganized to protect workers and customers. All of that will take time and money. Fiscal and monetary policies must aim to speed the recovery and minimize the recession’s lasting effects.

The Federal Reserve has moved swiftly and forcefully in this crisis. It eased monetary policy in March by lowering the federal funds rate, the overnight interest rate on loans between banks, nearly to zero and indicating that it plans to keep rates low for several years. Low interest rates probably had limited economic benefits in the spring. Lockdowns prevented people from spending or working more. However, we expect low rates will spur spending in sectors like housing as the economy reopens. And the Fed may well do more in coming months as re-opening proceeds and as the outlook for inflation, jobs, and growth becomes somewhat clearer. In particular, to maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) likely will provide forward guidance about the economic conditions it would need to see before it considers raising its overnight target rate. And it likely will clarify its plans for further securities purchases (quantitative easing). It is possible, though not certain, that the FOMC will also implement yield-curve control by targeting medium-term interest rates. It could, for example, target two-year rates by announcing its willingness to buy two-year Treasury notes at a fixed yield. The completion of the Fed’s internal review of its tools and framework in coming months will help guide these decisions.

The Fed also has been active beyond monetary policy.

First, the Fed has served as market maker of last resort by acting to stabilize critical financial markets when capital or other regulatory constraints have interfered with normal market-making or arbitrage. The Fed has served this role for repurchase agreements (repos) since September, when intermittent liquidity shortages led to spikes in repo rates. Banks did not provide liquidity to offset these spikes, as they normally would, citing balance sheet limits and other constraints. Because repo markets are critical to the functioning of broader financial and credit markets, as well as for the transmission of monetary policy, the Fed has restored more-normal function in repo markets by conducting large-scale repo operations and by steadily increasing the quantity of reserves in the banking system.

An even larger shock occurred in March, when uncertainty about the pandemic led hedge funds and others to scramble to raise cash by selling longer-term securities. The upsurge in the supply of longer-term securities, including Treasuries, was more than dealers and other market-makers could handle. Key financial markets, including for Treasury securities, experienced substantial volatility. To stabilize these markets, which like the repo market play a critical role in our financial system, the Fed purchased large quantities of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, again serving as market maker of last resort. It also set up a new repo facility to allow foreign official institutions to borrow dollars, using their Treasury reserves as collateral, thus avoiding the need to sell those Treasuries. Although risk and liquidity premiums in these key markets have returned closer to normal, at some point the Fed and the Treasury will need to review why the market-making facilities in place before the pandemic hit did not work more efficiently.

Second, the Fed has served as lender of last resort to the financial system, a classic function of central banks. Banks and other financial intermediaries typically borrow short and lend long—that is, they rely heavily on short-term funding to finance long-term loans and investments. If they lose their short-term funding—because their funders lose confidence or for other reasons—they can be forced to sell their assets in fire sales, restrict credit to customers, and, in extreme cases, become insolvent. Central banks can short-circuit that dangerous dynamic by lending to financial institutions against good collateral, replacing the lost liquidity. In the 2007-2009 crisis, which centered on the financial system and included a global financial panic, the Fed as lender of last resort took many actions to provide liquidity to financial institutions, with the goal of stabilizing the system and preserving the flow of credit to the economy.

Fortunately, the financial system is in much better shape today than in was during the financial crisis. Banks in particular are strong, with much higher levels of capital and liquidity. The Fed nevertheless has once again taken steps to ensure that the financial system has sufficient liquidity. Largely replicating our playbook from the crisis era, the Fed has eased terms on the discount window (which provides short-term loans to banks); re-established the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (which lends to broker-dealers); and established a facility that lends indirectly to money market mutual funds, ensuring that the funds can meet depositor withdrawals. In a novel step, the Fed also created a facility that lends to banks, without recourse, against Payroll Protection Program loans, ensuring that banks have sufficient funds to make those loans.

Under the heading of lender of last resort to the financial system, establishing currency swap lines with fourteen foreign central banks was one of the most important actions the Fed took in the 2007-2009 crisis. The Fed has revived this program. Currency swap lines allow foreign central banks (who assume all the credit risk) to lend dollars to banks in their jurisdictions. The broad availability of dollar liquidity is essential because most global banks do substantial borrowing and lending in dollars, including lending within the United States. The swap lines sustain the flow of dollar credit and reduce volatility in dollar-based markets, to the benefit of the U.S. economy.

Third, the Federal Reserve, with the support of the Congress and the Treasury, has also served during the current crisis as a lender of last resort to the non-financial sector, backstopping key credit markets facing the prospect of severe disruption from the pandemic. To take on this role, the Fed invoked its emergency lending powers under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Since those powers require that the Fed’s lending be well secured, it has had to rely on funds appropriated by the Congress and allocated by the Treasury to cover possible losses. Using these authorities, the Fed revived financial crisis-era facilities to stabilize commercial paper and asset-backed securities markets. Going beyond the financial crisis playbook, the Fed has also added new facilities to lend to corporations and state and local governments and to buy outstanding corporate bonds.

These programs have not extended much credit, so far, but that does not mean they have not succeeded. By establishing the programs, the Fed gave private investors the confidence to re-engage by reassuring them that the government would not allow these critical markets to become dysfunctional. Indeed, the corporate and municipal bond markets largely stabilized after the announcements, before any loans were made. Of course, if these markets seize up again, the Fed’s programs can extend credit.

The Fed also established the Main Street Lending Program to lend (through banks) to medium-sized companies. It is too soon, however, to judge its performance. This program is very different from anything the Fed has attempted before and poses difficult technical challenges. Although the Fed took many public comments while setting up the program, and made substantial changes, questions remain about how many banks and borrowers will participate. The Fed and Treasury may have to further ease terms for borrowers and increase incentives for banks for this program to have the desired effect. Or, the Fed and Treasury could add a new facility, along the lines of funding-for-lending programs run by the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, that simply subsidize banks for making additional loans to qualifying borrowers (for example, businesses below a certain size). That approach leaves the underwriting decision completely with the banks, while the size of the subsidy can be adjusted as needed to achieve the desired level of lending.

Finally, the Fed has also taken actions as a bank regulator—for example, encouraging banks to work with borrowers hobbled by the pandemic. It decided recently, based on stress test results, to bar stock buybacks by banks and to limit—but not eliminate—their dividends. Based on our experience in the global financial crisis, we think the Fed may find it needs to go further. Although banks are currently strong, it is possible the pandemic will so damage the economy that credit losses mount rapidly. For a successful recovery, the banking system must remain strong and able to lend.

Is there more the Fed could do? As we noted, the Fed likely will provide more clarity about its monetary policy plans, and it may need to adjust the terms or borrower eligibility requirements of its various lending facilities. Broadly speaking, though, the Fed’s response has been forceful, forward-looking, and comprehensive. But, as Chair Powell often notes, the Fed’s authorities allow it to lend, not spend. Some households and firms will need subsidies or grants, rather than loans, and spending is, of course, the province of the Congress.

The fiscal response to the pandemic has thus far been quite effective. Enhanced unemployment insurance and the Paycheck Protection Program have helped unemployed workers and their families, together with many businesses, survive the spring shutdowns. The fiscal support for the Fed’s lending programs likely will help preserve credit availability, possibly with only a portion of the allocated funds being spent.

However, some programs authorized by the Congress are ending, and new actions are necessary. Our recommendations for further fiscal action are:

First, Congress should develop a comprehensive plan to support medical research; increase testing, contact tracing and hospital capacity; make available critical supplies; and support state and local efforts to safely open businesses, schools, and public transportation.

Nothing is more important for restoring economic growth than improving public health. Investments in this area are likely to pay off many times over.

Second, with unemployment still very high, enhanced unemployment insurance should be extended, and complementary programs like food stamps should be adequately funded. Unemployment insurance could be restructured to deal with the incentive problems that some have noted, for example, by capping total payments at a fixed percentage of regular income. Rather than making a one-time appropriation, the Congress should create an automatic stabilizer by tying supplementary unemployment insurance and other support programs to the national unemployment rate or state unemployment rates. Under this approach, supplementary support will flow if conditions worsen, without further congressional action, and will automatically decline as conditions improve. This approach would provide people with aid when they most need it and would also help stabilize the economy as a whole by supporting income and stimulating spending automatically when the unemployment rate is high.

Third, Congress should provide substantial support to state and local governments. These governments are on the front line in providing critical services, including first responders, public health, education, and public transportation. State and local governments have been leading the way in designing a safe re-opening of the economy. The enormous loss of revenue from the recession, together with the new responsibilities imposed by the pandemic, has put state and local budgets deeply in the red. With limited capacity to run deficits, these governments will have to lay off workers and limit essential services unless they get federal help. As we learned after the financial crisis, fiscal contraction at the state and local level slows the national economy and offsets the benefits of federal action. To allow state and local governments to continue to provide essential services, and to avoid the recessionary effects of major state and local spending cuts, federal support should be substantial and without overly restrictive conditions on the aid.

Following our advice would further increase the already record-level federal budget deficit. With interest rates extremely low and likely to remain so for some time, we do not believe that concerns about the deficit and debt should prevent the Congress from responding robustly to this emergency. It remains important to use national resources wisely, with well-designed and effective programs. And, at some point, we will have to think through how to ensure the long-run sustainability of federal finances. The top priorities now, however, should be protecting our citizens from the pandemic and pursuing a strong and equitable economic recovery.

My view

Everything written above in essay will lead to lower dollar and higher inflation along with higher asset prices of securities which will benefit from this strong cocktail of Monetary and fiscal policy with added support from capping of bond yields. US is following the path of post world war II when they capped the bond yields and nominally defaulted on their bond obligations. This way they were also able to reduce their debt burden