Louise Gave was interviewed by Tyler Hay of Evergreen Gavekal on above topics.

Summary

On Supply Chains

I think the question around global supply chains is already a big focus of the US presidential campaign. The arrow in President Trump’s quiver is to say that this all happened because China is an untrustworthy partner. There’s going to be tremendous pressure on industries coming out of this to reduce their exposure to the international supply chain.

I wrote a piece at the beginning of this crisis called “Exponential Optimization.” I think that if you look at the past decade, we’ve lived in a world where everything has been optimized as much as possible. That includes optimizing balance sheets, share buybacks, and portfolios; but it also meant optimizing the supply chain. If that meant businesses could find a producer in the middle of Wuhan, China that would produce goods cheaper than alternatives, then they would do business there. Of course, the idea of producing things in Wuhan might no longer seem like the best idea.

One of the first things to look at when constructing a portfolio is how much government pressure will be placed on a business to produce at home rather than in China, which will undoubtably impact margins. Take healthcare as an example. We live in a world where 90% of antibiotics are produced in China. Is that something that the government will feel comfortable with going forward? My guess is that drug companies around the world will be told that if they want to sell their drugs somewhere, they have to be produced at home without regard to cost. We can’t live in a world where all of our drugs are produced somewhere else.

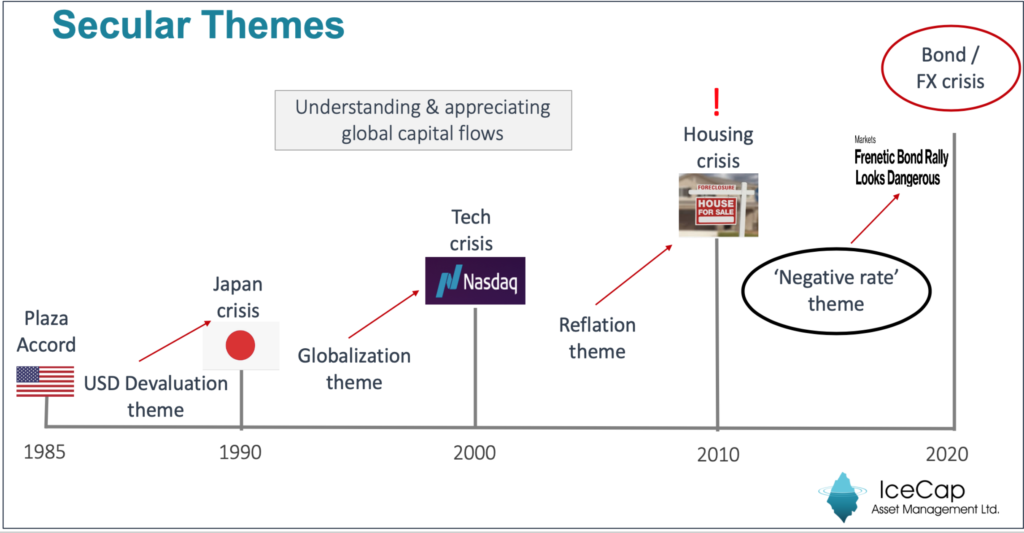

We had a 30-year stretch of globalization in the supply chain, but it turns out that finding the cheapest producer actually has an embedded cost that we weren’t recognizing. Now that we’re recognizing this cost, we’re finding out that it’s actually really, really high. I think there will be big disruptions to the global supply chain and people will probably want to invest in companies that aren’t going to be massively dislocated from needing to relocate their supply chains.

On Inflation vs Deflation

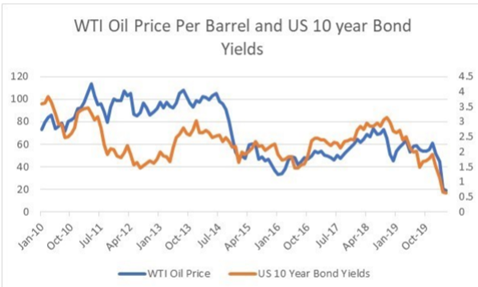

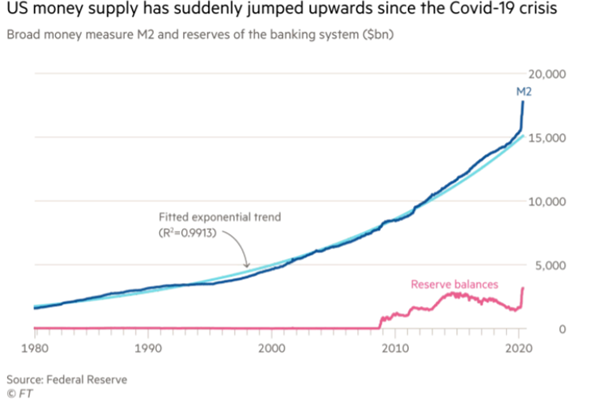

As a firm, Gavekal has been firmly in the deflationary camp for years and years. The reason for this is that every shock to the system was a fundamentally deflationary shock in that it didn’t really reduce supply – in fact, it often increased supply – but it did destroy demand. If you take the 2008 crisis as an example, we saw Quantitative Easing (QE) 1, 2, and 3, and a lot of people made the case that this was going to lead to a massive inflationary problem. But what people missed is China’s response to the crisis. It went on a capital and infrastructure spending boom such as the world has never seen. Up until 2008, if you were producing in China that meant you were either producing in Shenzhen or Shanghai. The production base for China was actually relatively small at that point. After the huge infrastructure spending boom China went through in 2008, you could produce in many other cities in China. The 2008 crisis resulted in nearly 500 million Chinese workers joining the global economy, which was a fundamentally deflationary shock. At the same time, oil prices were at $150/barrel and companies were pouring into new production all around the world. As money poured into energy infrastructure, oil prices came down over the next several years and today we’re much, much lower. Of course, the current economic hit means a destruction in demand, but the big question today is what happens to supply. What I see in the energy space is capital spending being slashed, so if I’m projecting three years down the road, I don’t think there will be an increase in supply of energy but a deterioration in the supply of energy.

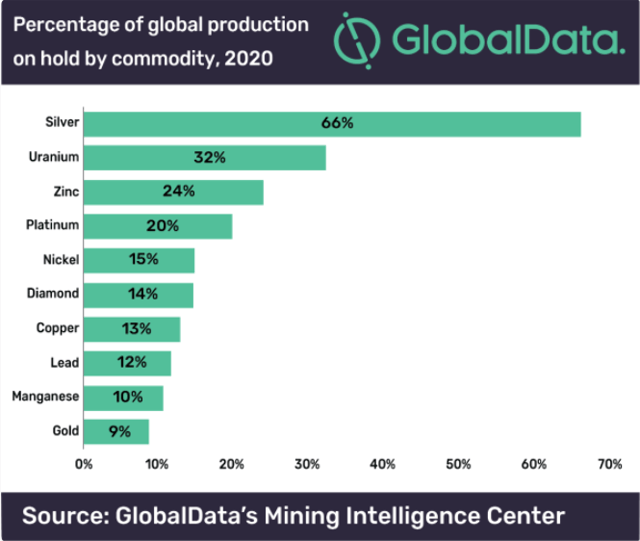

Similarly, I don’t think that there will be an increase in the supply of workers. I think that the world will turn their backs on the Chinese workforce. Instead of bringing a supply of 500 million workers to the global economy, we’re going to be pushing them back. So even though I see a destruction in demand, for the first time in quite a while, I also see a destruction in supply. In fact, this entire crisis is really about a destruction in supply. We’re now seeing it in industry after industry.

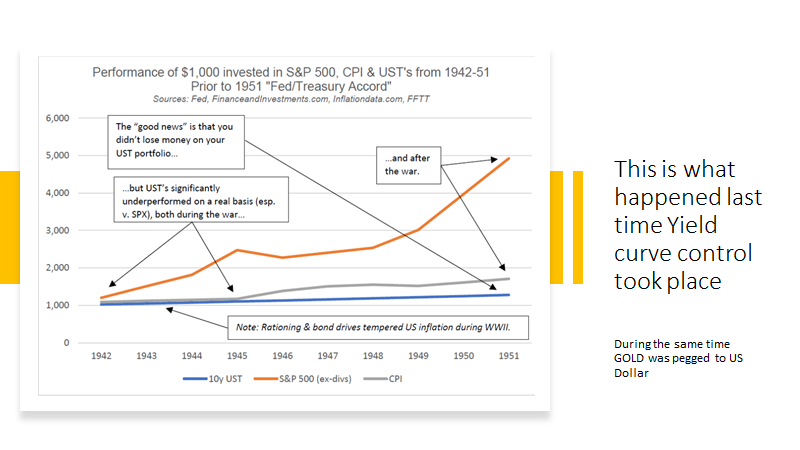

My big fear is that if you look at the TIPS market (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities), it’s now projecting inflation of 1.1% every year in the US for the next ten years. Aside for 2008, the US hasn’t had an inflation rate of 1.1% in the modern era. Now we’re supposed to have 10 years in a row?

Right now, the rate of inflation is 1.5%. What happens over the next six months if, instead of going to 1.1% as the market anticipates, inflation goes to 2.0% or 2.5% as the result of supply chain disruptions? I think that would create a whiff of panic in the markets. I’m much more afraid of inflation that’s not priced in, than deflation that’s fully priced into markets.