by Gail Tverberg via ourfiniteworld.com

Citizens seem to be clamoring for shutdowns to prevent the spread of COVID-19. There is one major difficulty, however. Once an economy has been shut down, it is extremely difficult for the economy to recover back to the level it had reached previously. In fact, the longer the shutdown lasts, the more critical the problem is likely to be. China can shut down its economy for two weeks over the Chinese New Year, each year, without much damage. But, if the outage is longer and more widespread, damaging effects are likely.

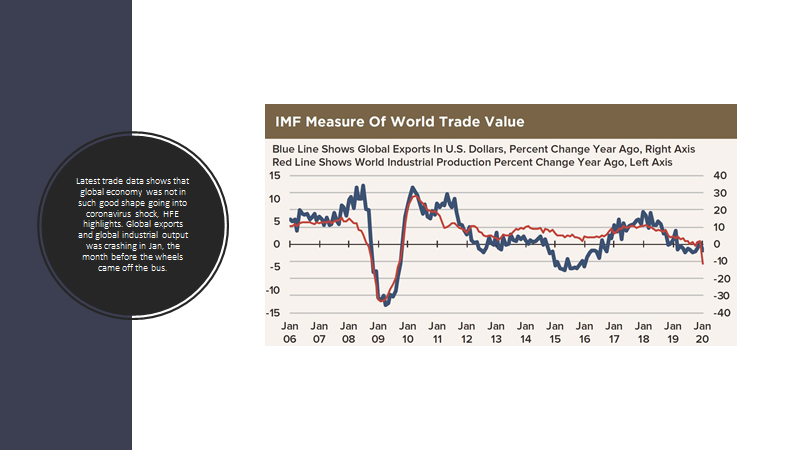

A major reason why economies around the world will have difficulty restarting is because the world economy was in very poor shape before COVID-19 hit; shutting down major parts of the economy for a time leads to even more people with low wages or without any job. It will be very difficult and time-consuming to replace the failed businesses that provided these jobs.

When an outbreak of COVID-19 hit, epidemiologists recommended social distancing approaches that seemed to be helpful back in 1918-1919. The issue, however, is that the world economy has changed. Social distancing rules have a much more adverse impact on today’s economy than on the economy of 100 years ago.

Governments that wanted to push back found themselves up against a wall of citizen expectations. A common belief, even among economists, was that any shutdown would be short, and the recovery would be V-shaped. False information (really propaganda) published by China tended to reinforce the expectation that shutdowns could truly be helpful. But if we look at the real situation, Chinese workers are finding themselves newly laid off as they attempt to return to work. This is leading to protests in the Hubei area.

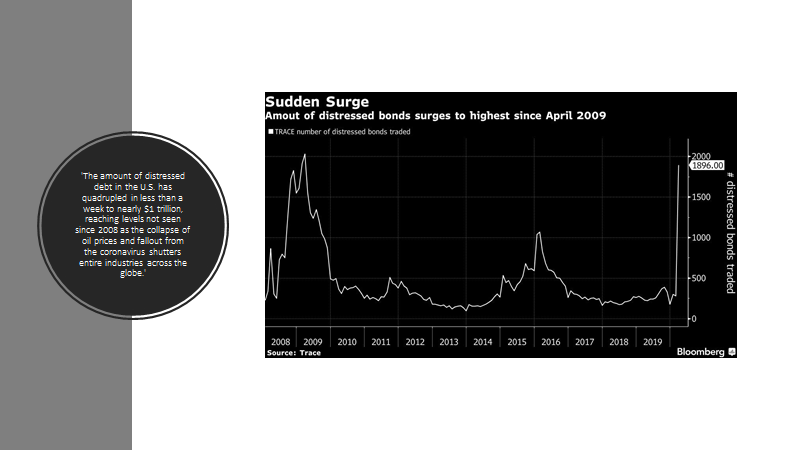

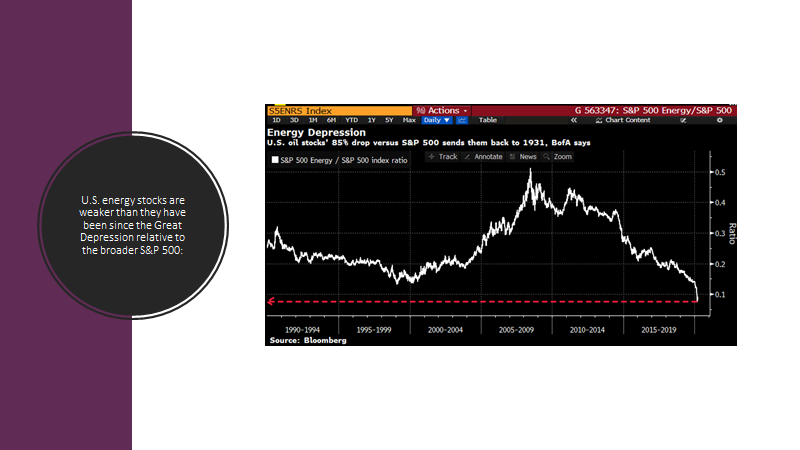

My analysis indicates that now, in 2020, the world economy cannot withstand long shutdowns. One very serious problem is the fact that the prices of many commodities (including oil, copper and lithium) will fall far too low for producers, leading to disruption in supplies. Broken supply chains can be expected to lead to the loss of many products previously available. Ultimately, the world economy may be headed for collapse.

In this post, I explain some of the reasons for my concerns.

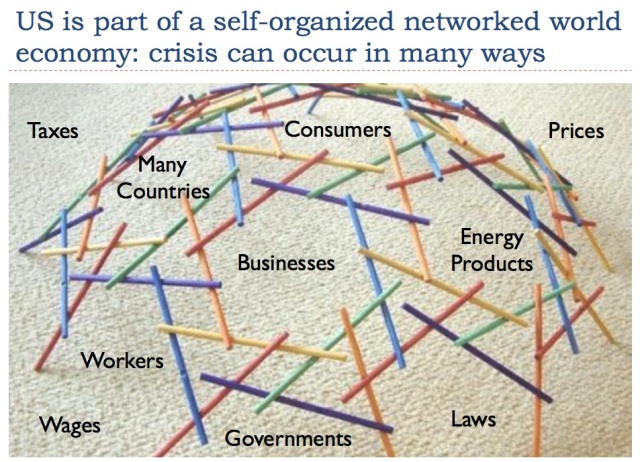

[1] An economy is a self-organizing system that can grow only under the right conditions. Removing a large number of businesses and the corresponding jobs for an extended shutdown will clearly have a detrimental effect on the economy.

Figure 1. Chart by author, using photo of building toy “Leonardo Sticks,” with notes showing a few types of elements the world economy.

An economy is a self-organizing networked system that grows, under the right circumstances. I have attempted to give an idea of how this happens in Figure 1. This is an image of a child’s building toy. The growth of an economy is somewhat like building a structure with many layers using such a toy.

The precise makeup of the economy is constantly changing. New businesses are formed, and new consumers grow up and take jobs. Governments enact laws, partly to collect taxes, and partly to ensure fair treatment of all. Consumers decide which products to buy based on a combination of factors, including their level of wages, the prices being charged for the available goods, the availability of debt, and the interest rate on that debt. Resources of various kinds are used in producing goods and services.

At the same time, some deletions are taking place. Big businesses buy smaller businesses; some customers die or move away. Products that become obsolete are discontinued. The inside of the dome becomes hollow from the deletions.

If a large number of businesses are closed for an extended period, this will have many adverse impacts on the economy:

- Fewer goods and services, in total, will be made for the economy during the period of the shutdown.

- Many workers will be laid off, either temporarily or permanently. Goods and services will suddenly be less affordable for these former workers. Many will fall behind on their rent and other obligations.

- The laid off workers will be unable to pay much in taxes. In the US, state and local governments will need to cut back the size of their programs to match lower revenue because they cannot borrow to offset the deficit.

- If fewer goods and services are made, demand for commodities will fall. This will push the prices of commodities, such as oil and copper, very low.

- Commodity producers, airlines and the travel industry are likely to head toward permanent contraction, further adding to layoffs.

- Broken supply lines become problems. For example:

- A lack of parts from China has led to the closing of many automobile factories around the world.

- There is not enough cargo capacity on airplanes because much cargo was carried on passenger flights previously, and passenger flights have been cut back.

These adverse impacts become increasingly destabilizing for the economy, the longer the shutdowns go on. It is as if a huge number of deletions are made simultaneously in Figure 1. Temporary margins, such as storage of spare parts in warehouses, can provide only a temporary buffer. The remaining portions of the economy become less and less able to support themselves. If the economy was already in poor shape, the economy may collapse.

[2] The world economy was approaching resource limits even before the coronavirus epidemic appeared. This is not too different a situation than many earlier economies faced before they collapsed. Coronavirus pushes the world economy further toward collapse.

Reaching resource limits is sometimes described as, “The population outgrew the carrying capacity of the land.” The group of people living in the area could not grow enough food and firewood using the resources available at the time (such as arable land, energy from the sun, draft animals, and technology of the day) for their expanding populations.

Collapses have been studied by many researchers. The book Secular Cycles by Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov analyze eight agricultural economies that collapsed. Figure 2 is a chart I prepared, based on my analysis of the economies described in that book:

Figure 2. Chart by author based on Turchin and Nefedov’s Secular Cycles.

Economies tend to grow for many years before the population becomes high enough that the carrying capacity of the land they occupy is approached. Once the carrying capacity is hit, they enter a stagflation stage, during which population and GDP growth slow. Growing debt becomes an issue, as do both wage and wealth disparity.

Eventually, a crisis period is reached. The problems of the stagflation period become worse (wage and wealth disparity; need for debt by those with inadequate income) during the crisis period. Changes tend to take place during the crisis period that lead to substantial drops in GDP and population. For example, we read about some economies entering into wars during the crisis period in the attempt to gain more land and other resources. We also read about economies being attacked from outside in their weakened state.

Also, during the crisis period, with the high level of wage and wealth disparity, it becomes increasingly difficult for governments to collect enough taxes. This problem can lead to governments being overthrown because of unhappiness with high taxes and wage disparity. In some cases, as in the 1991 collapse of the central government of the Soviet Union, the top level government simply collapses, leaving the next lower level of government.

Strangely enough, epidemics also seem to occur within collapse periods. The rising population leads to people living closer to each other, increasing the risk of transmission. People with low wages often find it increasingly difficult to eat an adequate diet. As a result, their immune systems easily succumb to new communicable diseases. Part of the collapse process is often the loss of a significant share of the population to a communicable disease.

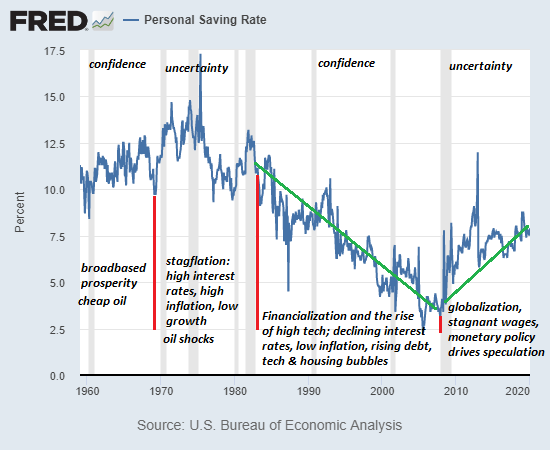

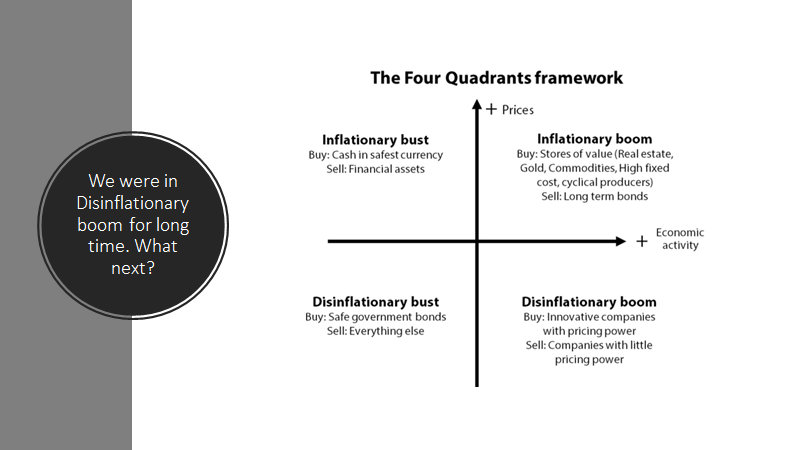

Looking back at Figure 2, I believe that the current economic cycle started with the use of fossil fuels back in the 1800s. The world economy hit the stagflation period in the 1970s, when oil supply first became constrained. The Great Recession of 2008-2009 seems to be a marker for the beginning of the crisis period in the current cycle. If I am right in this assessment, the world economy is in the period in which we should expect crises, such as pandemics or wars, to occur.

The world was already pushing up against resource limits before all of the shutdowns took place. The shutdowns can be expected to push with world economy toward a more rapid decline in output per capita. They also appear to increase the likelihood that citizens will try to overthrow their governments, once the quarantine restrictions are removed.

[3] The carrying capacity of the world today is augmented by the world’s energy supply. A major issue since 2014 is that oil prices have been too low for oil producers. The coronavirus problem is pushing oil prices even lower yet.

Strangely enough, the world economy is facing a resource shortage problem, but it manifests itself as low commodity prices and excessive wage and wealth disparity.

Most economists have not figured out that economies are, in physics terms, dissipative structures. These are self-organizing systems that grow, at least for a time. Hurricanes (powered by energy from warm water) and ecosystems (powered by sunlight) are other examples of dissipative structures. Humans are dissipative structures, as well; we are powered by the energy content of foods. Economies require energy for all of the processes that we associate with generating GDP, such as refining metals and transporting goods. Electricity is a form of energy.

Energy can be used to work around shortages of almost any kind of resource. For example, if fresh water is a problem, energy products can be used to build desalination plants. If lack of phosphate rocks is an issue for adequate fertilization, energy products can be used to extract these rocks from less accessible locations. If pollution is a problem, fossil fuels can be used to build so-called renewable energy devices such as wind turbines and solar panels, to try to reduce future CO2 pollution.

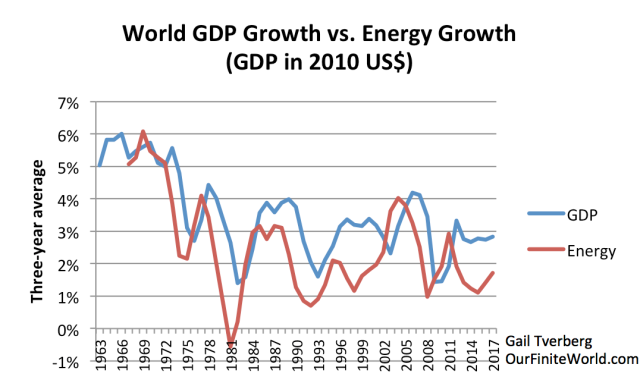

The growth in energy consumption correlates quite well with the growth of the world economy. In fact, increases in energy consumption seem to precede growth in GDP, suggesting that it is energy consumption growth that allows the growth of GDP.

Figure 3. World GDP Growth versus Energy Consumption Growth, based on data of 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy and GDP data in 2010$ amounts, from the World Bank.

The thing that economists tend to miss is the fact that extracting enough fossil fuels (or commodities of any type) is a two-sided price problem. Prices must be both:

- High enough for companies extracting the resources to make an after tax profit.

- Low enough for consumers to afford finished goods made with these resources.

Most economists believe that an inadequate supply of energy products will be marked by high prices. In fact, the situation seems to be almost “upside down” in a networked economy. Inadequate energy supplies seem to be marked by excessive wage and wealth disparity. This wage and wealth disparity leads to commodity prices that are too low for producers. Current WTI oil prices are about $20 per barrel, for example (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Daily spot price of West Texas Intermediate oil, based on EIA data.

The low-price commodity price issue is really an affordability problem. The many people with low wages cannot afford goods such as cars, homes with heating and air conditioning, and vacation travel. In fact, they may even have difficulty affording food. Spending by rich people does not make up for the shortfall in spending by the poor because the rich tend to spend their wealth differently. They tend to buy services such as tax planning and expensive private college educations for their children. These services require proportionately less commodity use than goods purchased by the poor.

The problem of low commodity prices becomes especially acute in countries that produce commodities for export. Producers find it difficult to pay workers adequate wages to live on. Also, governments are not able to collect enough taxes for the services workers expect, such as public transit. The combination is likely to lead to protests by citizens whenever the opportunity arises. Once shutdowns end, these countries are especially in danger of having their governments overthrown.

[4] There are limits to what governments and central banks can fix.

Governments can give citizens checks so that they have enough funds to buy groceries. This may, indeed, keep the price of food products high enough for food producers. There may still be problems with broken supply lines, so there may still be shortages of some products. For example, if there are eggs but no egg cartons, there may be no eggs for sale in grocery stores.

Central banks can act as buyers for many kinds of assets such as bonds and even shares of stock. In this way, they can perhaps keep stock market prices reasonably high. If enough gimmicks are used, perhaps they can even keep the prices of homes and farms reasonably high.

Central banks can also keep interest rates paid by governments low. In fact, interest rates can even be negative, especially for the short term. Businesses whose profitability has been reduced and workers who have been laid off are likely to discover that their credit ratings have been downgraded. This is likely to lead to higher interest costs for these borrowers, even if interest rates for the most creditworthy are kept low.

One area where governments and central banks seem to be fairly helpless is with respect to low prices for commodities used by industry, such as oil, natural gas, coal, copper and lithium. These commodities are traded internationally, so it is not just their own producers that need to be propped up; the market intervention needs to affect the entire world market.

One approach to raising world commodity prices would be to buy up large quantities of the commodities and store them somewhere. This is impractical, because no one has adequate storage for the huge quantities involved.

Another approach for raising world commodity prices would be to try to raise worldwide demand for finished goods and services. (Making more finished goods and services will use more commodities, and thus will tend to raise commodity prices.) To do this, checks would somehow need to go to the many poor people in the world, including those in India, Bangladesh and Nigeria, allowing these people to buy cars, homes, and other finished goods. Sending out checks only to people in one’s own economy would not be sufficient. It is unlikely that the US or the European Union would undertake a task such as this.

A major problem after many people have been out of work for a quite a while is the fact that many of these people will be behind on their regular payments, such as rent and car payments. They will be in no mood to buy a new vehicle or a new cell phone, simply because they have been offered a check that covers groceries and not much more. They will remain in a mode of cutting back on purchases, not adding more. Demand for most kinds of goods will remain low.

This lack of demand will make it difficult for business to have enough sales to make it profitable to reopen at the level of output that they had previously. Thus, employment and sales are likely to remain depressed even after the economy seems to be reopening. China seems to be having this problem. The Wall Street Journal reports China Is Open for Business, but the Postcoronavirus Reboot Looks Slow and Rocky. It also reports, Another Shortage in China’s Virus-Hit Economy: Jobs for College Grads.

[5] There is a significant likelihood that the COVID-19 problem is not going away, even if economies can “bend the trend line” with respect to new cases.

Bending the trend line has to do with trying to keep hospitals and medical providers from being overwhelmed. It is likely to mean that herd immunity is built up slowly, making repeat outbreaks more likely. Thus, if social isolation is stopped, COVID-19 illnesses can be expected to revisit prior locations. We know that this has been an issue in the past. The Spanish Flu epidemic came in three waves, over the years 1918-1919. The second wave was the most deadly.

A recent study by members of the Harvard School of Public Health says that the COVID-19 epidemic may appear in waves until into 2022. In fact, it could be back on a seasonal basis thereafter. It also indicates that more than one period of social distancing is likely to be required:

“A single period of social distancing will not be sufficient to prevent critical care capacities from being overwhelmed by the COVID-19 epidemic, because under any scenario considered it leaves enough of the population susceptible that a rebound in transmission after the end of the period will lead to an epidemic that exceeds this capacity.”

Thus, even if the COVID-19 problem seems to be fixed in a few weeks, it likely will be back again within a few months. With this level of uncertainty, businesses will not be willing to set up new operations. They will not hire many additional employees. The retired population will not run out and buy more tickets on cruise ships for next year. In fact, citizens are likely to continue to be worried about airplane flights being a place for transmitting illnesses, making the longer term prospects for the airline industry less optimistic.

Conclusion

The economy was already near the edge before COVID-19 hit. Wage and wealth disparity were big problems. Local populations of many areas objected to immigrants, fearing that the added population would reduce job opportunities for people who already lived there, among other things. As a result, many areas were experiencing protests because of unhappiness with the current economic situation.

The shutdowns temporarily cut back the protests, but they certainly do not fix the underlying situations. Instead, the shutdowns add to the number of people with very low wages or no income at all. The shutdowns also reduce the total quantity of goods and services available to purchase, regardless of how much money is added to the system. Many people will end up poorer, in some real sense.

As soon as the shutdowns end, it will be obvious that the world economy is in worse condition than it was before the shutdown. The longer the shutdowns last, the worse shape the world economy will be in. Thus, when businesses are restarted, we can expect even more protests and more divisive politics. Some governments may be overthrown, or they may collapse without being pushed. I fear that the world economy will be further down the road toward overall collapse.