Satyajit writes on a subject which is also my conviction that ….The “everything bubble” is deflating. The fact that it’s happening relatively slowly shouldn’t blind us to the real threat: The world is dangerously underestimating how hard it’ll be to deal with the fallout once it pops.

Frothy markets can’t disguise the warning signs. The shift to tighter monetary policies in the West is putting pressure on global equity and real estate values. Even more critically, it’s weakening credit markets. Over-indebted emerging markets face headwinds from rising borrowing costs and dollar shortages.

Investment Managers must “Go Digital or Die”

The following is an excerpt of an article that I published in the March/April 2017 issue of Investments and Wealth Monitor, [i] We feel strongly that the sentiment is just as relevant today as it was then.

Fintech thought leader Paolo Sironi argues that for wealth management firms it’s “go digital or die.” Such a provocative statement may be fear-mongering, but it should not go unheeded. Sironi points out, “Nowadays, the unveiling of the asymmetry of information is forcing wealth managers to rethink their product-driven approach at a time of declining margins and establish a healthier relationship with final customers based on clearer client/portfolio-centric methods. ” [ii] In other words, the wealth management firms that will survive and thrive will be the ones that embrace automation in both their investment operations and digital delivery.

Read More

Skate Where the Puck’s Going, Not Where It’s Been

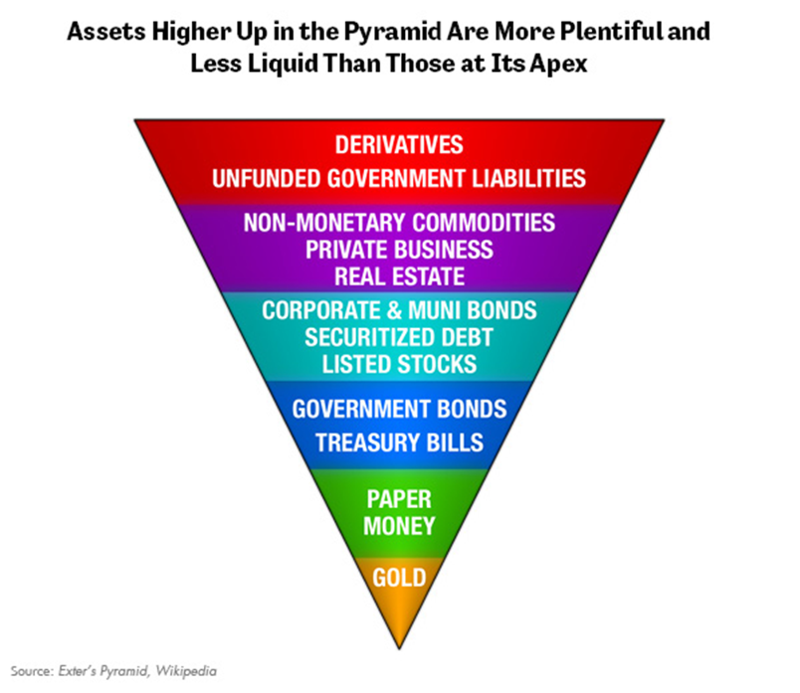

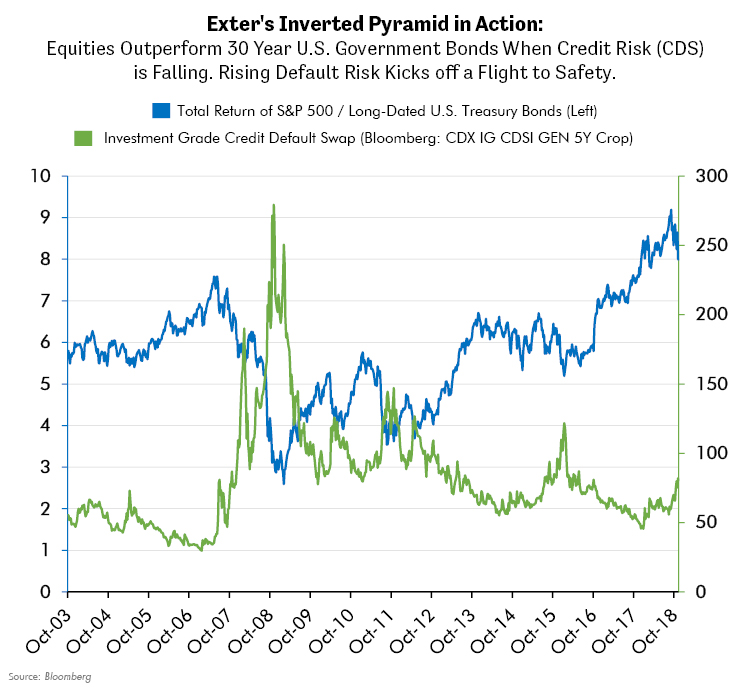

Lewis Johnson writes …. there are three key indicators we have generally found trustworthy to gauge real-time risk appetite. These provide insight into where we are in the cycle. These three market-based, forward looking indicators are 1.) credit default swaps (CDS,) 2.) interest rate expectations, and 3.) the relative performance of gold.

We believe the graph above is strongly suggestive of a deeper truth: that rising CDS can mark the beginning of a turn in risk taking appetite. We believe that this relationship of credit leading equities is causal. The job of CDS is to hedge default risk in bonds. Since bonds are a senior claim to equities in a company’s capital structure, rising problems (rising CDS) in the senior tranche (bonds) should mathematically suggest that problems in the junior tranche (equities) may follow. The credit markets are larger than equity markets and provide the needed flow of financing for commerce to thrive. If confidence in credit is falling – the perception of risk is rising. This could lead to a rising cost of debt and less accommodative debt financing, both of which can lower the fuel that finances a company’s growth.

Read More

https://blog.capitalwealthadvisors.com/trends-tail-risks/skate-where-puck-is-going

The Perils of Inflationism

Doug Noland writes …Credit is a financial claim – an IOU. New Credit creates purchasing power. Credit is self-reinforcing. When Credit is expanding, the creation of this new purchasing power works to validate the value of Credit generally. In general, new Credit promotes economic activity, both spending and investment, in the process promoting higher incomes. Credit expansions fuel higher price levels throughout the economy, including incomes, real estate, stocks and bonds. Higher perceived wealth stimulates self-reinforcing borrowing, spending and investment.

Traditionally, bank lending for business investment was a prevailing mechanism for finance to enter into the economic system. There were various mechanisms that worked to contain Credit expansions, including the gold standard and disciplined monetary regimes. As important, there were traditions against deficit spending, running persistent trade deficits and profligacy more generally. Moreover, there were bank reserve and capital requirements that placed constraints on lending and financial excess. In short, there was a limited supply of “money,” with excessive borrowing demands pressuring interest rates higher. There was certainly cyclicality, but systems tended toward adjustment and self-correction.

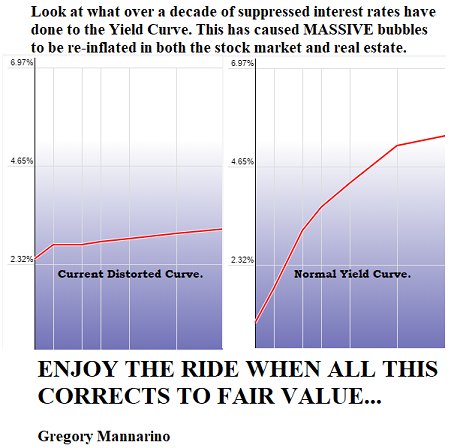

It’s not only the decade-long experiment with QE (with ultralow rates) that makes contemporary finance unique in history. As the key source of additional system “money” and Credit, banks and business investment were some time ago supplanted by market-based finance and leveraged securities/asset purchases. Contemporary (“digitalized”) finance expands virtually without constraint.

Meanwhile, finance entering the system to speculate on higher asset prices creates a very different dynamic than back when bank loans were financing capital investment. Excessive borrowing and investment placed downward pressure on profits, in the process reducing the incentive to borrow, invest and lend. In contrast, a system of unfettered “money” and Credit financing asset prices is acutely unstable. Expanding finance leads to higher asset prices and only greater impetus to borrow and speculate.

Going on a decade now, I’ve been chronicling the “global government finance Bubble.” It has not been ten years of systemic smooth sailing. History’s greatest Bubble stumbled in 2011 on fears of the Fed’s “exit strategy.” The Fed quickly backed off – and then proceeded to double its balance sheet again by 2014. Europe tottered badly in 2011 and 2012, inciting “whatever it takes” and a reckless ECB balance sheet gambit. Fed, ECB and global central bank liquidity stoked a historic boom throughout the emerging markets. China’s epic Bubble, pushed into overdrive with aggressive global crisis-period stimulus, inflated uncontrollably. All of it almost came crashing down in late-‘15/early-’16. But the Chinese adopted more stimulus, the ECB and BOJ boosted QE, and the Fed postponed “normalization.”

I believe the world over the past two years experienced a momentous speculative blow-off – in stocks, bonds, corporate Credit, real estate, M&A, art, collectibles, and so on. I would further argue that speculative melt-ups are quite problematic for contemporary finance. Surging asset prices spur rapid increases in speculative Credit, unleashing new self-reinforcing liquidity/purchasing power upon markets, financial systems and economies around the globe. The problem is it doesn’t work in reverse. The greater the price spikes, the more vulnerable markets become to destabilizing reversals. De-risking/deleveraging dynamics then see a contraction of speculative Credit, leading to problematic self-reinforcing destruction of marketplace liquidity.

As inflationism has demonstrated throughout history, QE was always going to be a most slippery slope. The notion of inflating risk asset markets with central bank liquidity has to be the most dangerous policy prescription in the sordid history of central banking. And, importantly, the longer central bankers held to this policy course the deeper were market structural distortions. Rather than attempting to rectify crucial flaws in contemporary finance, central bankers chose inflationism and market backstops as stabilization expedients. This was a monumental mistake.

The expansion of central bank balance sheets ensured a parallel expansion in global speculative leverage. Over time, there was an increasing multiplier effect on each new dollar/yen/euro/etc. of central bank “money.” The original Fed QE “money” program basically accommodated speculative deleveraging. In contrast, the past few years (in particular) incited an aggressive expansion of speculative leverage throughout global securities and asset markets.

In addition, the parabolic increase in central bank liquidity over recent years was instrumental in the parabolic ballooning of ETF assets and passive investment funds more generally. While not “leverage” in the conventional sense, the enormous growth in ETF/passive funds and associated risk misperceptions have amounted to a historic market distortion. Trillions flowed into risky stocks, bonds, corporate Credit, EM assets and derivative structures believing that these fund shares were a liquid store of (nominal) value. The phenomenon of perceived money-like ETF shares was integral to the global risk market speculative blow-off.

The problem with speculative blow-offs is that they inevitably reverse. Upon the reversal, the seriousness of the problem is proportional to the amount of underlying leverage, the degree of market misperceptions and the scope of associated market and economic structural maladjustment. The world now confronts one hell of a problem.

The unfolding de-risking/deleveraging dynamic is extraordinarily problematic from a liquidity standpoint. A powerful “risk off” dynamic – having unfolded following a global speculative blow-off instigated by massive central bank liquidity injections – leaves global “system” liquidity acutely vulnerable. Faltering global liquidity will now expose the misperception of “moneyness” for ETF and passive index products. As such, global markets are now at high risk to global de-risking/deleveraging fomenting a transformative change in risk perceptions. Past risk reassessments (that seem minor compared to what is now unfolding) have led to panic and dislocation.

Flawed central bank policies are directly responsible for both a decade-long global Bubble and the more recent speculative blow-off. Markets, meanwhile, cling to the belief that central bankers remain fully committed to doing “whatever it takes” to hold bear markets, recessions and crises at bay. There’s a disconnect. The harsh reality is that “whatever it takes” has failed. It was built on fallacious notions of inflationism, markets and finance, more generally. Most regrettably, a tremendous amount of market hopes, dreams and capitalization have been built on little more than fallacy.

Total global Credit growth has slowed dramatically. I would argue speculative (securities and derivative-related) Credit, having evolved into a key marginal source of total global Credit, is now in significant self-reinforcing contraction. This portends liquidity issues for markets, faltering asset values and trouble for economies. In the markets, Fear is supplanting greed. Risk aversion and waning liquidity now spawn powerful Contagion across markets.

Read More

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2018/12/weekly-commentary-perils-of-inflationism.html

Charts That Matter

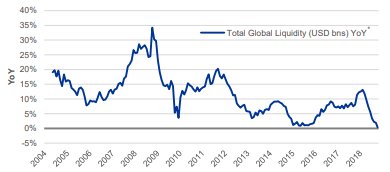

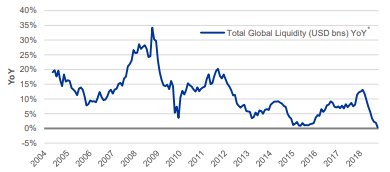

BlackRock estimate of Global Liquidity is also showing the lowest reading in their data series.

A picture is worth a thousand words…

CFOs are more focused on defensive strategies than they’ve been all cycle that’s why Capex is sacrificed for buybacks.

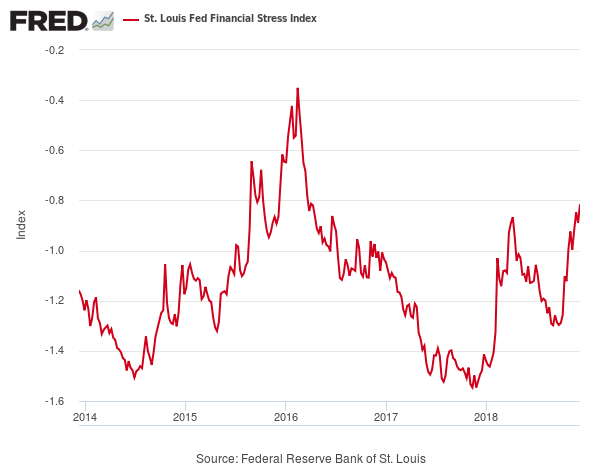

Financial stress in US is at a two and half year high. (capitalspectator.com)

Winning at the Great Game: Interview with Adam Robinson -Farnam Street

Farnam street did a fantastic interview with , Adam Robinson. If you don’t know who Adam is, let me give you a little background. He is the man who cracked the SAT before co-founding The Princeton Review and in fact, wrote the only test preparation book to become a New York Times best seller.

Adam is a rated chess master with a Life Title and was actually personally mentored by Bobby Fischer. He was an undergrad at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and later earned a law degree at Oxford University.

Here are a few highlights from our discussion:

The Great Game is life. We play many games in life. The game of job, or career, or starting a business, or the politics game, or the education game. Everything is a game. Games suggest something that’s not serious, but of course games are intensely serious. If you want to find someone who is ferociously intense and focused, watch someone playing a game, especially something competitive.

Constitutionally, I’m an introvert, and so the revelation of 2016, into 2017 and now 2018, has been that the real magic is connecting with others. That if you want to do anything in the world, and this is as true personally as well as professionally, it’s all about creating a vision for others to join.

Our views of the world are reflected back to ourselves by the internet, so we become more hardened in our own views, right? In fact, all we see is exactly what we expect to see. The internet and technology is one big confirmation bias engine.

By quantitative measures, people should be happier, and yet they’re not. It’s the exact opposite, right? The irony is that we have material wealth undreamt of. The average person today lives better than the average king a couple of centuries ago. And yet — we’re not happier.

One of the problems with self-help books is they rivet your attention on exactly the one thing it ought not to be focused on: yourself. You look at any of the great religious traditions, and the great philosophers, and the great poets, they all had the same message of focusing on others, and being of service to others. I think the people who are going on search to “find themselves,” will never find themselves. You find yourself only in the midst of others.

Here’s a clue that you’ve tapped into Truth with a capital T, and that your unconscious is speaking — it’s that the answer will surprise you. You’ll be startled by it.

When someone says, “It makes no sense that…” really what they’re saying is this: “I have a dozen logical reasons why gold should be going higher but it keeps going lower, therefore that makes no sense.” But really, what makes no sense is their model of the world, right? So I know when that happens, that there’s some other very powerful reason why gold keeps going lower that trumps all the “logical reasons.”

In America, we’ve deified “intelligence.” And the problem with “intelligence” is that it works against you. If you’re intelligent, you shouldn’t have to work too hard. Things should come pretty quickly, and if you aren’t intelligent, what’s the point? The better belief is that your success is determined by how hard you work. Then, it’s just a matter of choice. If you want something, work for it, and you will if you want it.

I think it’s important that parents let their children know, just to talk about parents for a sec, that learning is hard. You need to know that learning is hard. It’s not easy. Right? The reason you need to know it’s hard is that if you think it’s easy, as soon as you encounter difficulty, you’re going to think the problem is you. So you need to know it’s hard, going in.`

link for the Podcast

Macquarie: “We No Longer Live In Conventional Capitalism; There Are No Recognizable Cycles”

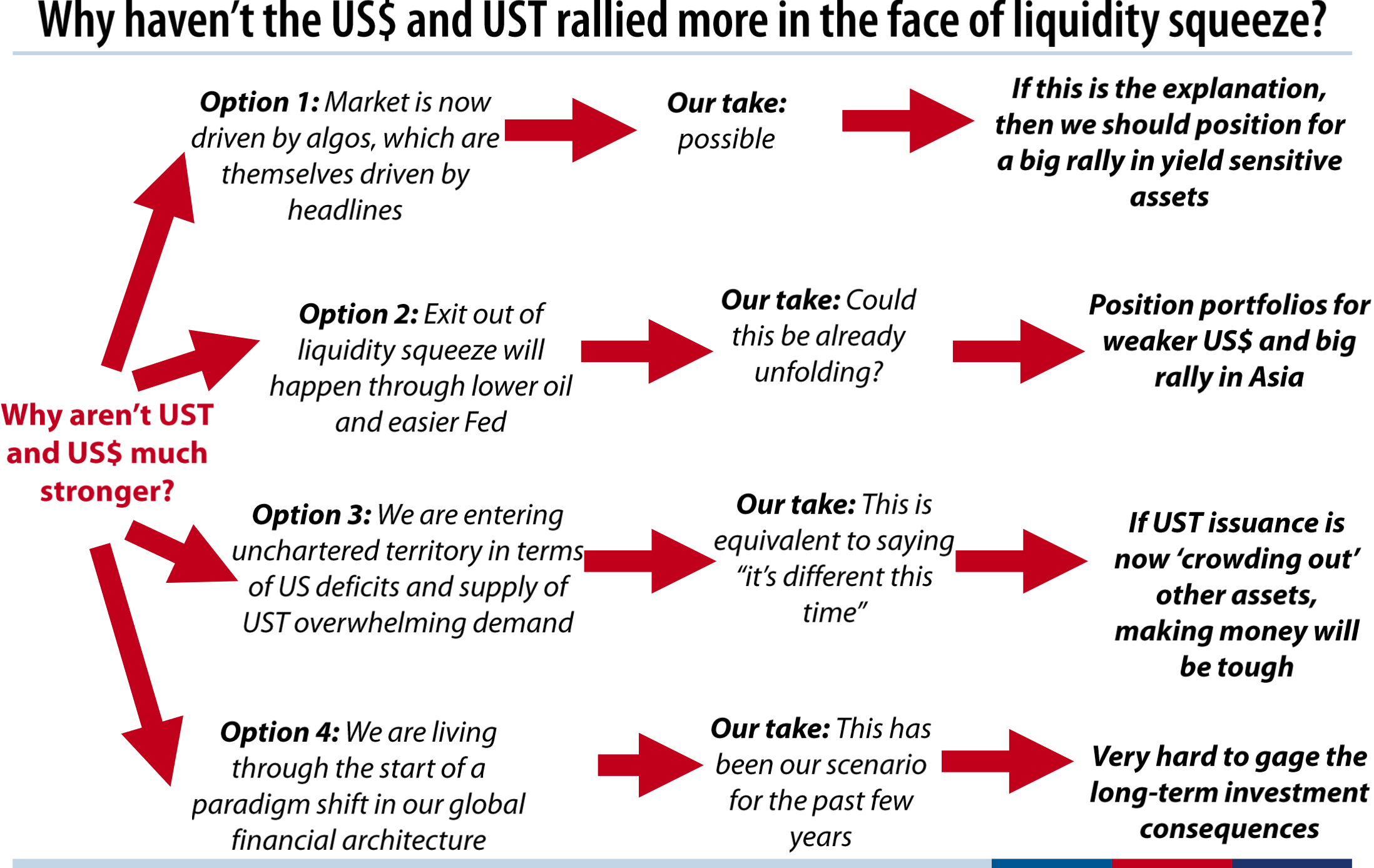

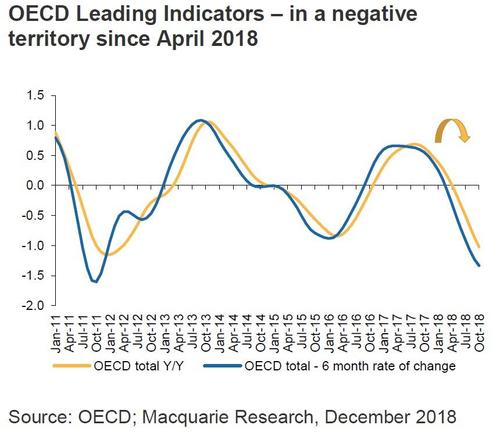

Victor Shvets writes ..Is the coast clear? It is not safe; too many sharks out there.As in ‘Jaws’, the question is whether it is safe to go back into water?A number of positive signals (China, Italy etc) are tempting investors back.

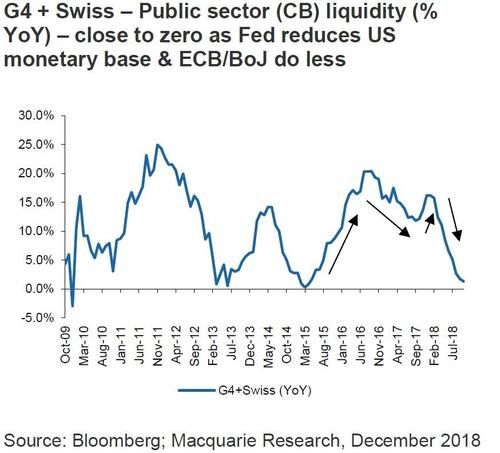

However, liquidity continues to drain and reflationary momentum is still weakening. It might all ‘turn on a dime’ but risks into ’19 remain high.

We never know what would break the camels’ back but…‘Well this is not a boat accident! It wasn’t any propeller! It wasn’t any coral reef! And it wasn’t Jack the Ripper! It was a shark!’ As in ‘Jaws’, investors are now trying to assess whether there are sharks out there in the dark waters ahead, and what signals should they watch? Is it trade, politics, CBs, extraditions, retaliations, fiscal stimuli, spreads, private equity (arguably the single most overvalued and least liquid asset class), FX, oil or other uncertainties that could sink the boat? Who is selling and what does it mean? As we saw in ‘97-98 or ‘08-09, trying to anticipate whether it would be Russia, LTCM, subprime or Lehman’s PN business that would change everything is a fruitless exercise. We will know when we do. The value of a single signal by itself is limited, and the headlines that ‘we have just discovered the signal’ are not worth much.

Having said that, there is an underlying ‘heart beat’ that tells investors whether the general direction is towards a greater disinflation or reflation. In a world dominated by asset prices, there is a need to generate more liquidity and debt than economies require. We no longer live in a conventional capitalism; there are no recognizable cycles, and late cycle arguments mean little, when public sectors determine their duration and strength.

In a modern economy, it is all about tax cuts, fiscal stimuli and manipulation of yield curves & rates. Indeed it makes sense, as generating excess liquidity & corralling volatilities is the only way to guide highly financialized economies. It does however lead to a Matrix world of random signals, turning what only days ago seemed solid into liquid.

…ultimately world does not work if liquidity drains & reflation slows

This brings us to the latest ‘signals’. First, we had Powell changing tune in space of less than eight weeks from ‘far from neutral’ to ‘just below neutral’, altering expectations of a tightening cycle, and pushing US$ lower. Second, we had a plethora of news regarding the trade war. China apparently agreed to buy a bit more US soybeans (~0.5m tons) and is willing to re-phrase and underemphasize its ‘China 2025 policy’. Third, it appears that the Italian populist Government is folding on its budget spending. It is enough to reflate sentiment and markets by lowering probabilities of more extreme outcomes.

Unless economies evolve in strongly positive or negative ways, it is this flow of random signals that drives markets, which in turn impacts economies in a complex and iterative process. However, at the end of the day, unless CBs reverse their contractionary stance, global liquidity would continue to drain, and unless China and US alter their policies, global reflationary momentum would weaken.

conclusion

The world cannot function unless China and the US see ‘eye to eye’ and Eurozone avoids implosion. It is possible that we might find a middle ground, but it would require a miracle; at least in the absence of a greater dislocation.

We maintain that while China would like to find a compromise, it can never give up its state-driven model and EU is still facing a revolution in ’19. There are also uncertainties of a divided Congress that could either lower or raise US$ (depending on whether US accepts slower growth or stimulates).

Despite recent relief, direction remains disinflationary; the coast is not clear

An important crossroad

Some fantastic set of charts on global markets by Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal

crossroadBlind to Luck

“Our tendency to see skill where there is just luck causes the successful to have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and the rest of us to be overly deferential to them. Very few people are luck egalitarians.”

Stumbling and Mumbling blog writes….In a good article on how graduating in a recession does long-lasting damage to one’s career, Tim Harford says “it’s easy to overlook luck.”

It is indeed. Evidence for this has been uncovered in experiments by Nattavudh Powdthavee and Yohanes Riyanto. They got students in Singapore and Thailand to bet upon tosses of a fair coin and found that people were willing to pay to back the bet of students who had correctly called previous tosses. “An average person is often happy to pay for what could only be described as transparently useless advice” they conclude.

This is startling. But it has been corroborated by other research: experiments in Barcelona have found exactly the same thing.

It’s also been found in the real world. This paper finds that investors:

fail to understand that, in large populations of mutual funds, a few will outperform by pure chance…In addition, investors do not sufficiently account for volatility and are thus likely to confuse risk taking with skill. In large mutual fund populations, this can lead to an over-allocation of capital to lucky past winners.

People over-estimate the signal-to-noise ratio in what is really volatile data, and so under-estimate the role of luck. A recent paper by economists at Elm Partners shows this. They asked people: how many tosses would you need to see to be 95% confident of distinguishing between a far coin and one with a 60% chance of coming up heads? The correct answer is 143. But most subjects answered 40 or less.

All this suggests people are indeed blind to the importance of luck and are too quick to see patterns: the technical term for this is apophenia.

The truth is, though, that luck is everywhere. William Goldman famously said that “nobody knows anything”, and that success is largely unpredictable. But nevertheless we laud those who are lucky enough to have backed success as if they know what they were doing. As Ed Smith writes in his lovely book, Luck: “randomness is routinely misinterpreted as skill.”

Why do people do this? I suspect it’s not just because of a lack of statistical literacy: many of the subjects in the experiments I’ve cited had taken statistics classes. It’s also because of two reinforcing biases. One is the outcome bias. We judge a performance by its result so if a team wins the game, or if a fund manager beats the market, we infer that they did well rather than got lucky. The other is the narrative fallacy. We are story-telling animals. We seek links between things and detailed explanations even if the truth is only that a bit of good luck happened, then a bit of bad. I suspect that most football punditry is like this.

All this is about how we attribute skill rather than luck to other people. But of course, we also do so to ourselves, and asymmetrically: good results are down to skill and bad to luck. A study of day traders has confirmed what you probably suspected:

Retail day traders in the forex market attribute random success to their own skill and, as a consequence, increase risk taking.

The upshot of all this is that the successful are apt to become bumptious arrogant prats because they attribute their success to their own talents rather than luck. And observers are apt to take them at their inflated self-estimation.

Why for example did the housing, communities and local government select committee ask Mike Ashley yesterday for his views on reviving high streets? Does Mr Ashley really know more than anybody else with years of working in retail? Or were MPs failing to see that companies can succeed in much the same way that some species do – because the environment selects for mutations which are in fact random and unintended? The mere fact the question is rarely asked (not just of Ashley) is itself significant.

This, of course, colours our whole social and political structure. Our tendency to see skill where there is just luck causes the successful to have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and the rest of us to be overly deferential to them. Very few people are luck egalitarians. This is one way – of perhaps many – in which inequality sustains itself.

https://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2018/12/blind-to-luck.html

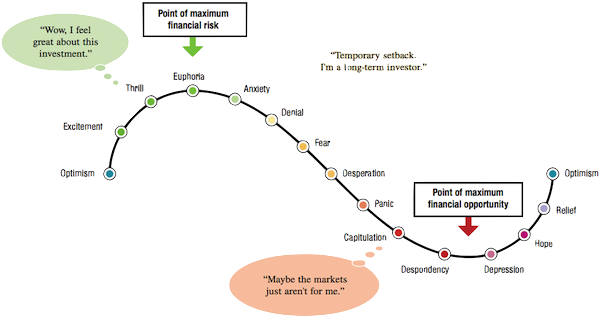

Where are we now in the investor cycle?

USAgold.com writes “Two months ago we warned of October being the month markets have been known to go bump in the night – 1907, 1929, 1987, 1997, 2007, 2008. Sure enough, on October 3 the Dow Jones Industrial closed at 26,828. By the end of the month, it stood at 25,116 – down over 1700 points and nearly 6.5%. Since then, stock market psychology has undergone a radical transformation – an abrupt reversal with important implications for the long term. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that “the investor trend that has helped buoy stocks over most of the past decade is showing signs of breaking down.”

So where would you put us now in the investor cycle depicted in the chart below?

We guesstimate that we are somewhere between “Euphoria” and “Anxiety” for stocks and “Depression” and “Hope” for gold and silver. In short, the time might be right for starting to leg-out of stocks and ladder-into gold. The last time we featured this chart in late September, we put stock market sentiment at somewhere between “Thrill” and “Euphoria” and gold somewhere between “Despondency” and “Depression.”

Read More