It’s their move now. They can win if they really want to.By John AuthersFebruary 25, 2021, 10:43 PM MST

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

What Just Happened?

Something big just happened in world markets. That I can prove. So I’ll start with the easy part of going through the remarkable events of the week, culminating in Thursday’s great drama, and showing that they’re a big deal. Then will come the much harder questions of why they happened, what might happen next, and what we should all do about it.

The bond market has been at the center of the drama. Yields are rising, especially in the often overlooked “belly” of the curve, between the closely observed two- and 10-year maturities. An unsuccessful auction of seven-year Treasuries certainly didn’t help, but the trend through the day was inexorable. This is what happened to the five-year Treasury yield:

Beyond the belly, however, which saw most action on Thursday, there has been a move away from duration, the technical term for bonds whose returns are most sensitive to changes in interest rates. Austria’s “century bond” issued in 2017 and not repaying its principal until 2117 is widely taken as the ultimate benchmark for duration; this is what has happened to its price:

While Treasuries, the world’s biggest bond market, understandably command the most attention, this isn’t just an American event. Before the market opened on Monday, Christine Lagarde of the European Central Bank stated that the bank was monitoring longer bond yields, causing them to fall sharply. That reversal didn’t last long. German bund yields are now higher than they were before she intervened (although as they remain negative it’s still a little hard to see why a central banker would feel they were too high):

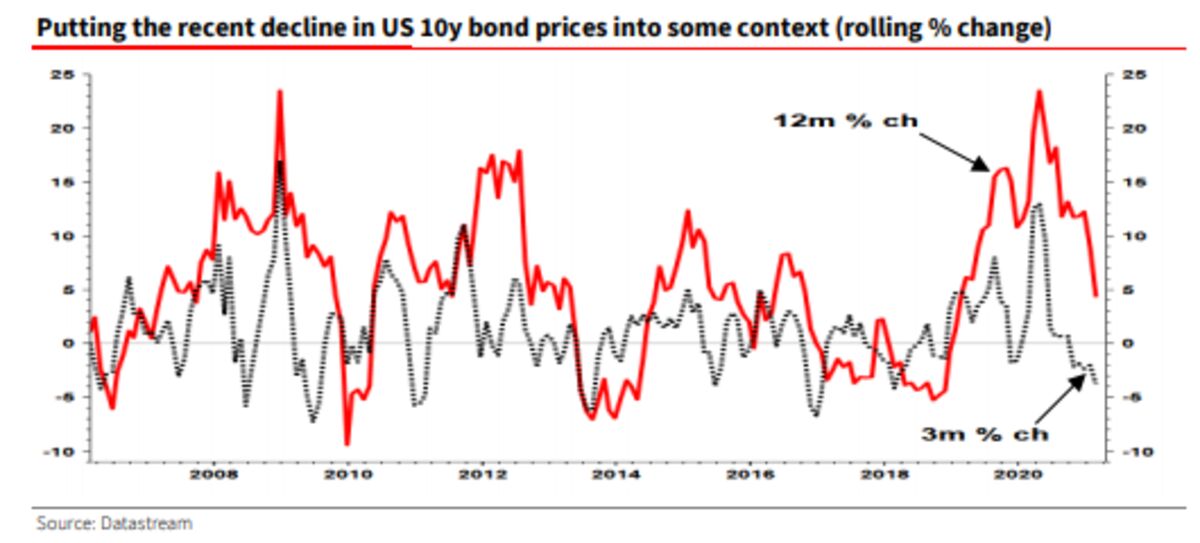

Serious moves are afoot, then. But it’s worth pointing out that there have been big falls in bond prices before during the post-crisis era. The following chart comes from Albert Edwards of Societe Generale SA:

This is a significant move for the bond market. It needn’t in its own right be anything unprecedented or game-changing.

Volatility

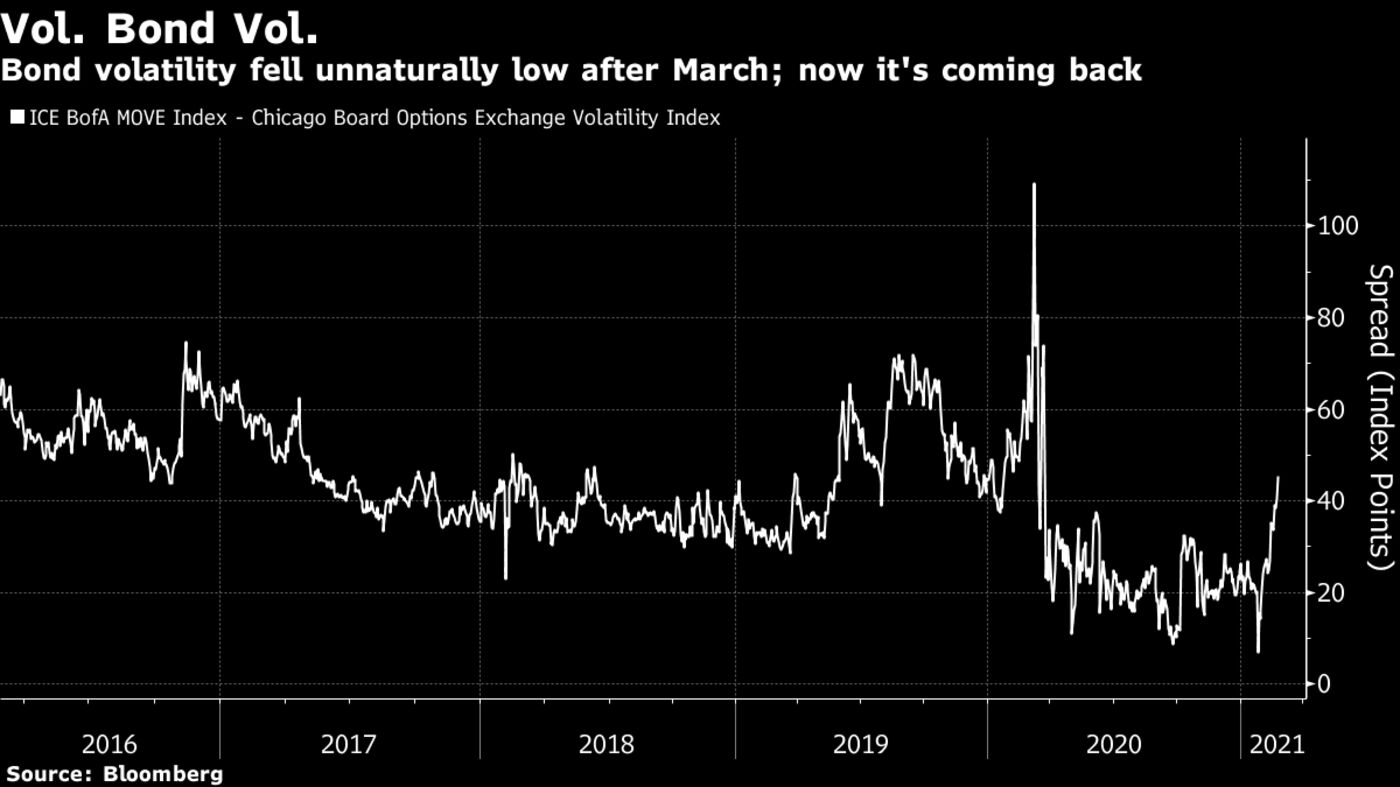

Bond volatility is also back. Following the brief but terrifying financial crisis that accompanied the onset of the pandemic in March last year, central banks succeeded in effectively anaesthetizing the bond market while measures of stock market volatility remained elevated. This shows up clearly in the spread of the CBOE VIX index of stock volatility over the MOVE index of bond volatility:

More fromStartups Sometimes Stretch the TruthU.S. Strikes Against Iran Sent the Right MessageDjibouti Is a Flashpoint in the U.S.-China Cold WarEtsy Is No Pandemic Flash in the Pan

It isn’t evident that central banks need be too uncomfortable with yields at current levels, which remain low. But their success in quashing seemingly all activity in the bond market seems to be over.

Mortgages

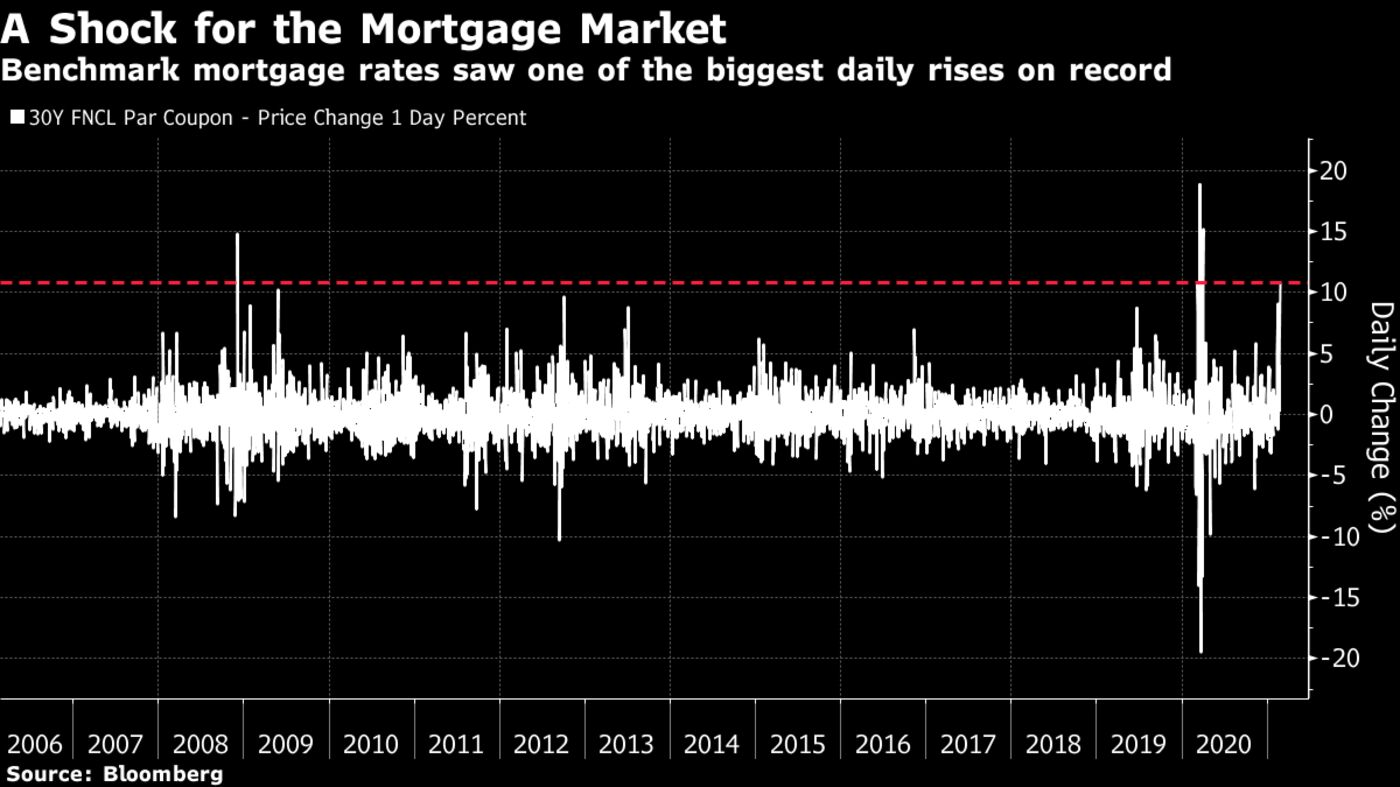

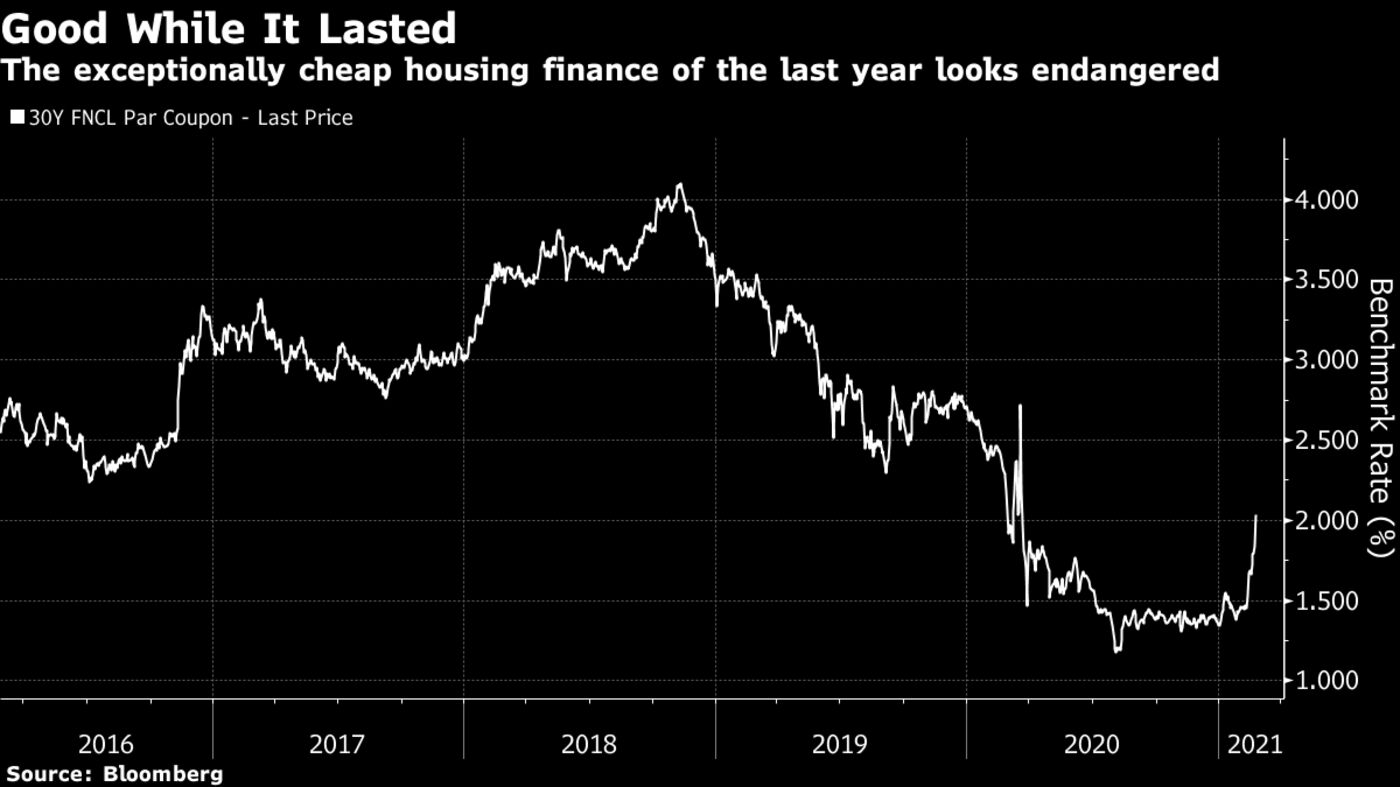

Why does this matter? There are a number of reasons. First, the bond market is central to setting interest rates for Americans’ mortgages. In proportionate terms, the shock to the Fannie Mae 30-year mortgage generally used as a benchmark for U.S. home loans was truly historic. Outside of one day during the worst of the 2008 crisis, and two days during the Covid shock last spring, it was the biggest percentage rise in mortgage rates on record:

To be clear, the sharp proportionate increase is enabled by the current low rates, although these have been the norm for a while. The rise could still endanger the U.S. housing recovery, a critical reason for optimism about the economy, if it continues:

Currencies

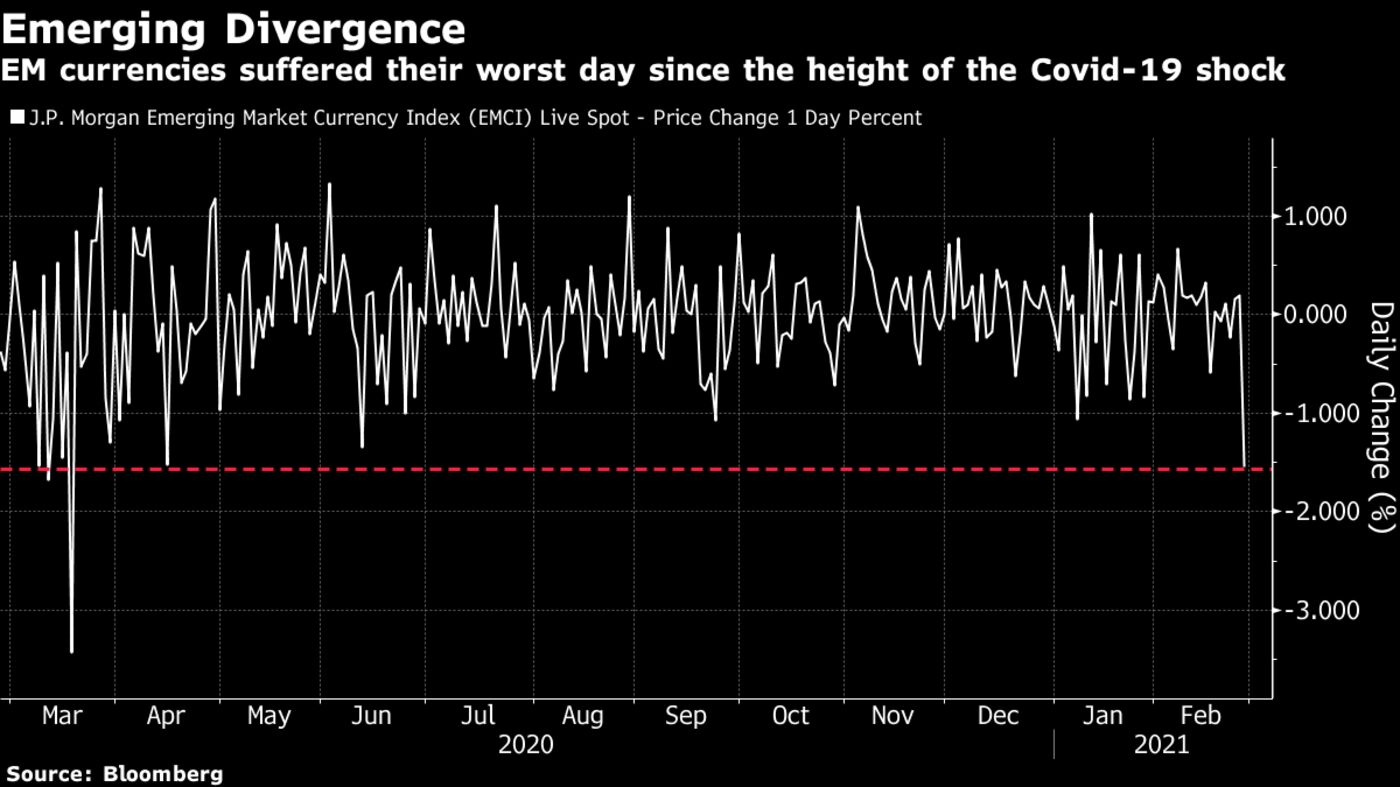

Higher U.S. rates are generally held to be bad news for emerging markets, as they attract flows away from the sector, and also tend to strengthen the dollar. That in turn can weaken emerging markets that are particularly reliant on dollar-denominated debt. Emerging market currencies had been enjoying a resurgence of late — until Thursday, when rising yields in the U.S. triggered their worst fall since March last year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s widely used benchmark:

Stocks

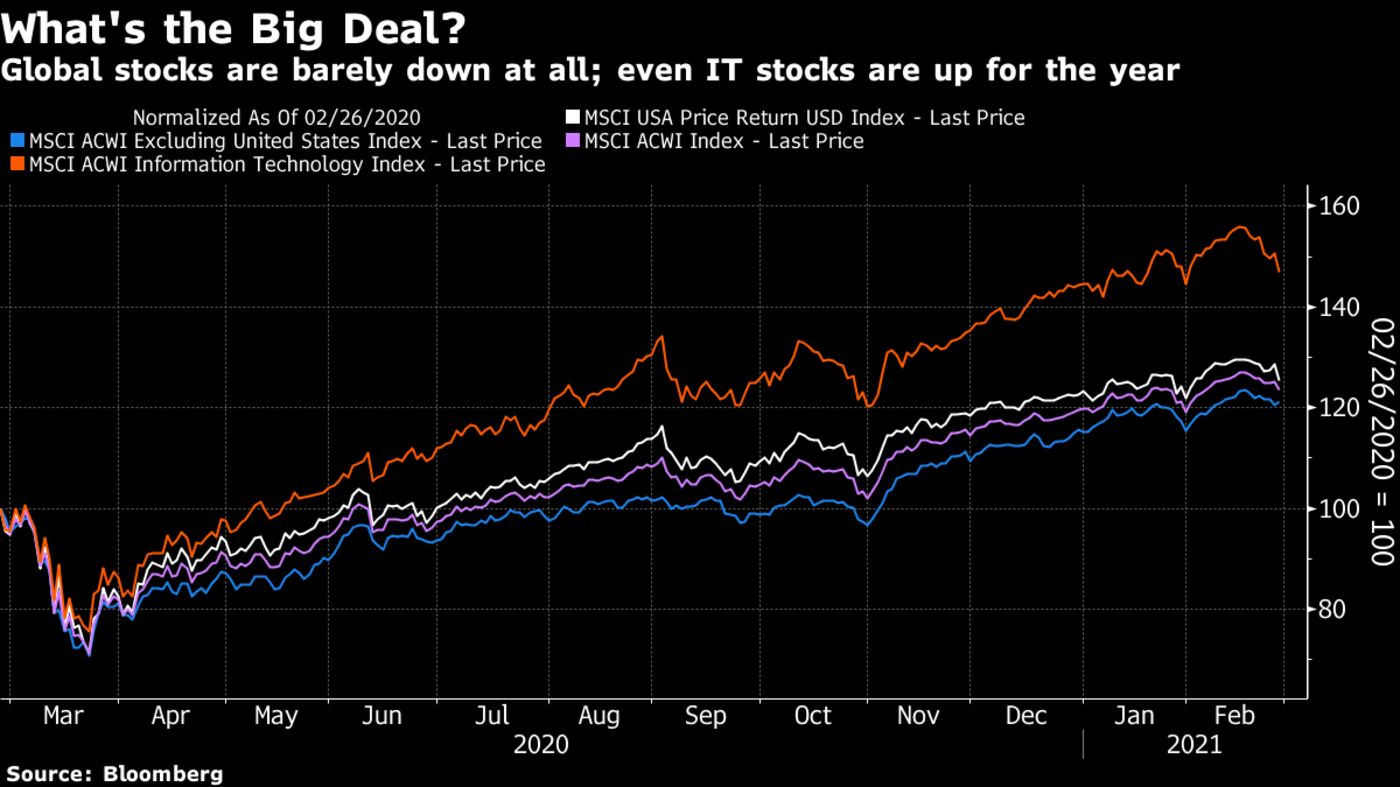

Last, and deliberately so, we come to stocks. As a whole, taking in all global stock markets, this isn’t yet much of a deal. MSCI’s index of global stocks excluding the U.S. actually rose slightly on Thursday. Even tech stocks, which are under undoubted pressure, are still up for 2021 so far after a great 2020:

Of all the main asset classes, stocks are the least scathed thus far. They’ve still commanded plenty of attention. That is because they matter most to politicians, and the Fed is (in perception at least) ultimately dedicated to making sure they don’t suffer a big fall. This was put beautifully by my late colleague Richard Breslow in the last column he wrote for Bloomberg in October last year:

As far as equities are concerned, they are the golden child. It’s really the only market the authorities care about. It pains me to admit, but they must be your first priority. Ugh.

The critical question at what point bond yields become too high for stocks to bear, and cause them to fall. The mantra for the last year, as equities have enjoyed their remarkable post-Covid rally, is that stocks remain cheap compared to bonds. This is true, but the people excitedly buying stocks on this basis might be forgetting that the situation can also be corrected by a fall for bonds, and not just by a rise for equities. The rally in stocks has run out of steam for now, but compared to long bonds (proxied by the relative performance of the popular SPY and TLT exchange-traded funds) their outperformance has now exceeded 100% since last March’s nadir.

Betting on stocks to beat bonds has been a good and well-supported bet. It doesn’t mean we can be guaranteed a stonking equity bull market into the middle distance. It might instead mean watching stocks follow bonds into a vicious bear market. That is the risk of over-reliance on equities’ cheapness compared to bonds when choosing to buy them despite their extreme high valuations compared to their own fundamentals. Just saying.

That risk, to be clear, hasn’t transpired as yet. It might never. Which brings us to the need to explain why all of this is happening.

Tantrums in Store

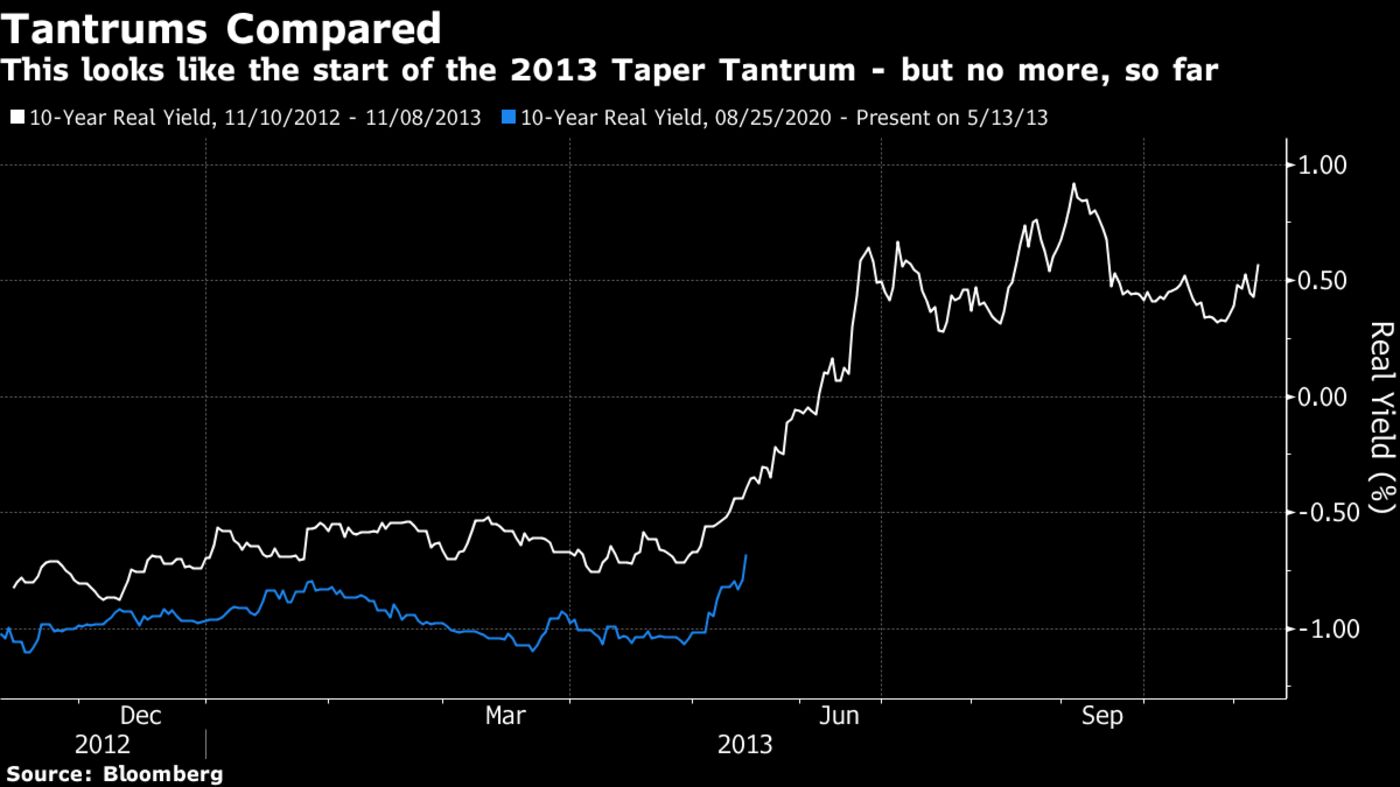

The great concern is the impact that further rises in bond yields could have on other asset classes, especially U.S. equities and emerging markets. There is one great prior example of a bond market “tantrum,” which followed comments by then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke about “tapering” bond purchases in May 2013. The effect on real yields, unprecedentedly negative at the time, was immediate. The following graph compares 10-year real yields in that incident with 10-year real yields over the last six months:

The pattern is obviously very similar to the pattern in May 2013 — but we have far further to go to match the tantrum of eight years ago.

What would cause this tantrum to go further? Plainly, the market is discounting a lot of reflation ahead, given the strength of the economic recovery that has already been priced in by stocks. All else equal, we would expect bond yields to go up and bond prices to fall, as the expansion to back up these high equity valuations comes to pass. The reason yields aren’t much higher already is that markets assume central banks will act to keep them under control. Lagarde, Jerome Powell and a battalion of other central bank governors have all made that clear over the last week.

For the remainder of this year, and with the market left to its own devices, the trajectory of bond yields depends above all on the course of the pandemic and the vaccination program to combat it. But for now, the issue to the exclusion of all else is to find out what central banks will do to back up their words on keeping yields low. The following comments from a note by Deutsche Bank AG’s currency strategist George Saravelos put it well:

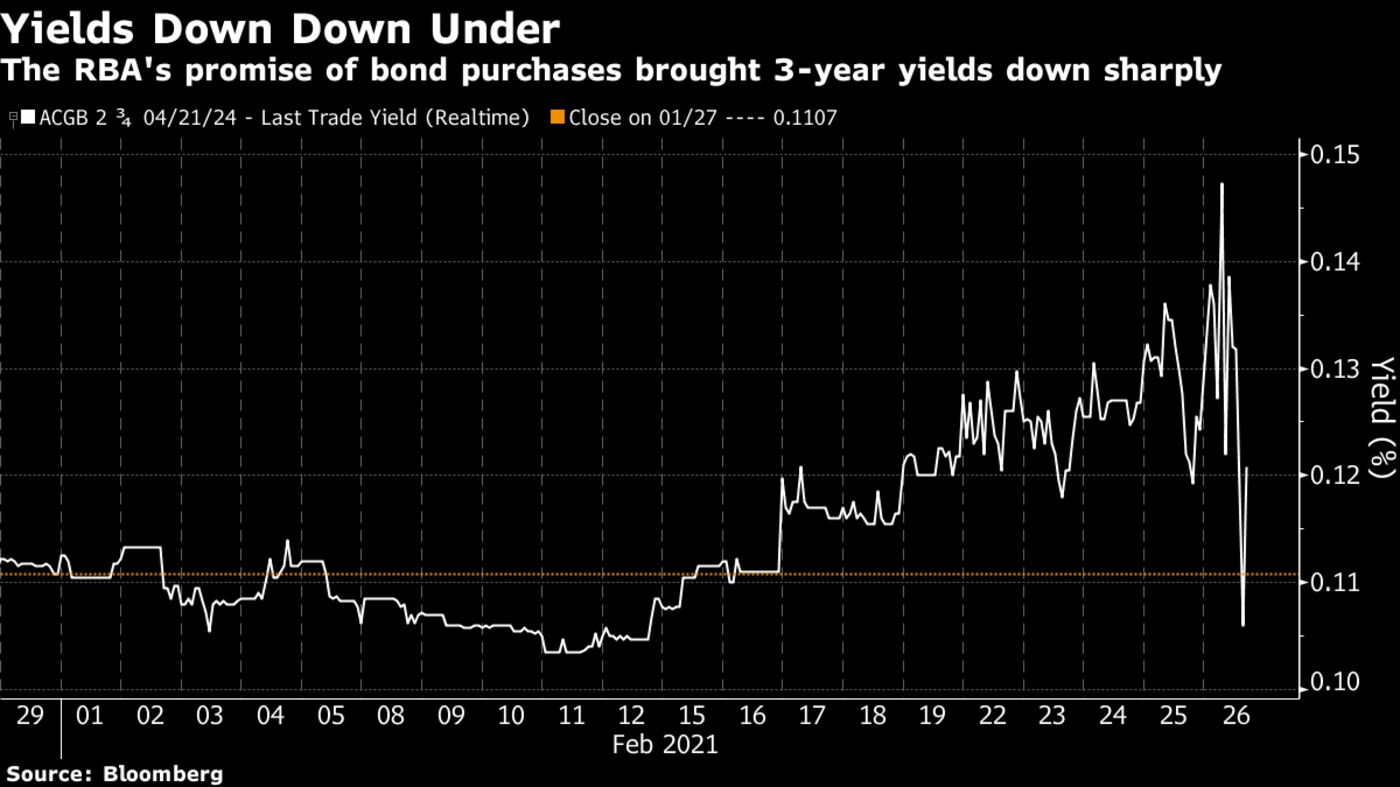

central banks are not impotent. This is not an attack on a currency peg with a self-fulfilling depletion of foreign currency reserves. Central bank pockets are literally infinitely deep in their own currency. The most straightforward response to today’s price action would be for the Reserve Bank of Australia to come in even more aggressively overnight to defend its 3-year yield target. [Which is exactly what has happened.] Similarly, for the ECB, where we have already seen the three most influential executive board members expressing concern. Even for the Fed, it is worth remembering that guidance is couched in terms of current QE of at least $120bn per month, providing in-built flexibility for an increase.

The current volatility – unaccompanied by improving inflation expectations and directly challenging central bank reaction functions – resembles a VaR shock for the market and risks leading to a broader tightening of financial conditions. How much it runs will ultimately be determined by how deep into their pockets central banks are willing to reach. We will find out over the next few days.

To illustrate Saravelos’s prediction about Australia’s central bank, which has already come true, the RBA announced that it would buy A$3 billion ($2.35 billion) of bonds to keep the three-year security to its targeted yield. This is what has happened to that yield, with an initial sharp reaction followed by a rebound. The test is ongoing, but central banks can win it if they really want to:

Emerging Markets

The 2013 taper tantrum had a minimal impact on developed market stocks. It had a briefly cataclysmic effect on emerging market currencies, particularly those of the five large countries with big deficits that went by the now long-forgotten acronym of the BIITS — Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa. This chart shows why the impression has taken hold that emerging markets need very low Treasury yields to prosper, comparing real 10-year yields to the relative performance of MSCI’s emerging and developed market stock gauges:

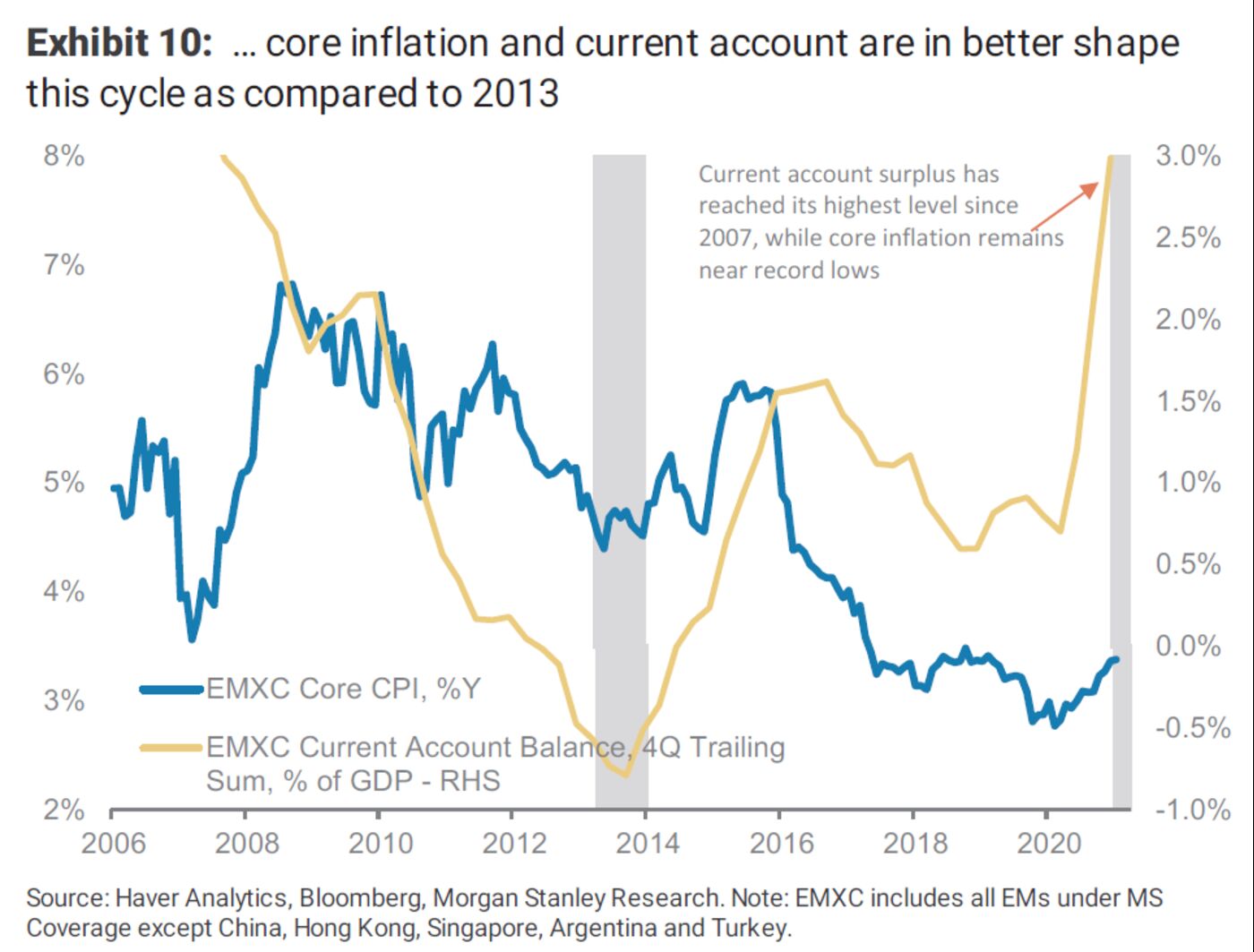

Could this happen again? Thankfully for emerging markets, there is evidence that it won’t, or at least not with full force. The following chart from Morgan Stanley shows core inflation and current account deficits for the emerging markets excluding China since 2006. The tantrum came just as they looked vulnerable; on both measures they look far more resilient now:

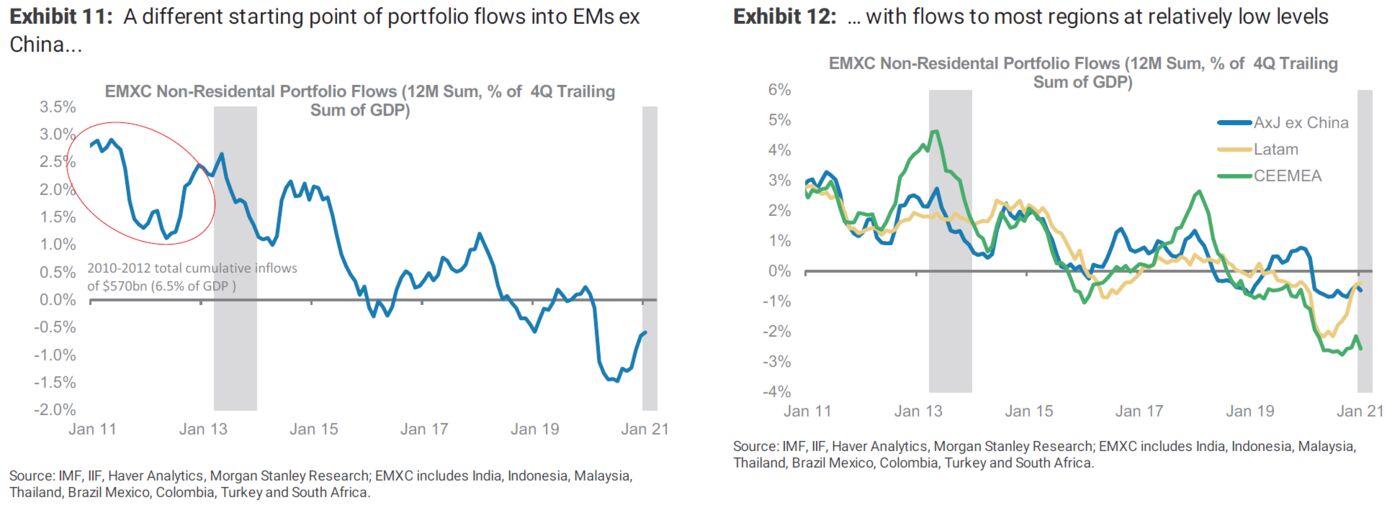

Another critical point is that the 2013 tantrum came shortly after the peak of a historic bull market for emerging markets that brought capital flowing in. There was plenty of foreign money ready to exit, and it did. This time the opposite is true:

The sell-off in emerging markets foreign exchange on Thursday shows that EM investors are on the alert for another tantrum. This isn’t good news for emerging markets. But the stakes are nowhere near as high as they were eight years ago.

Developed Stocks

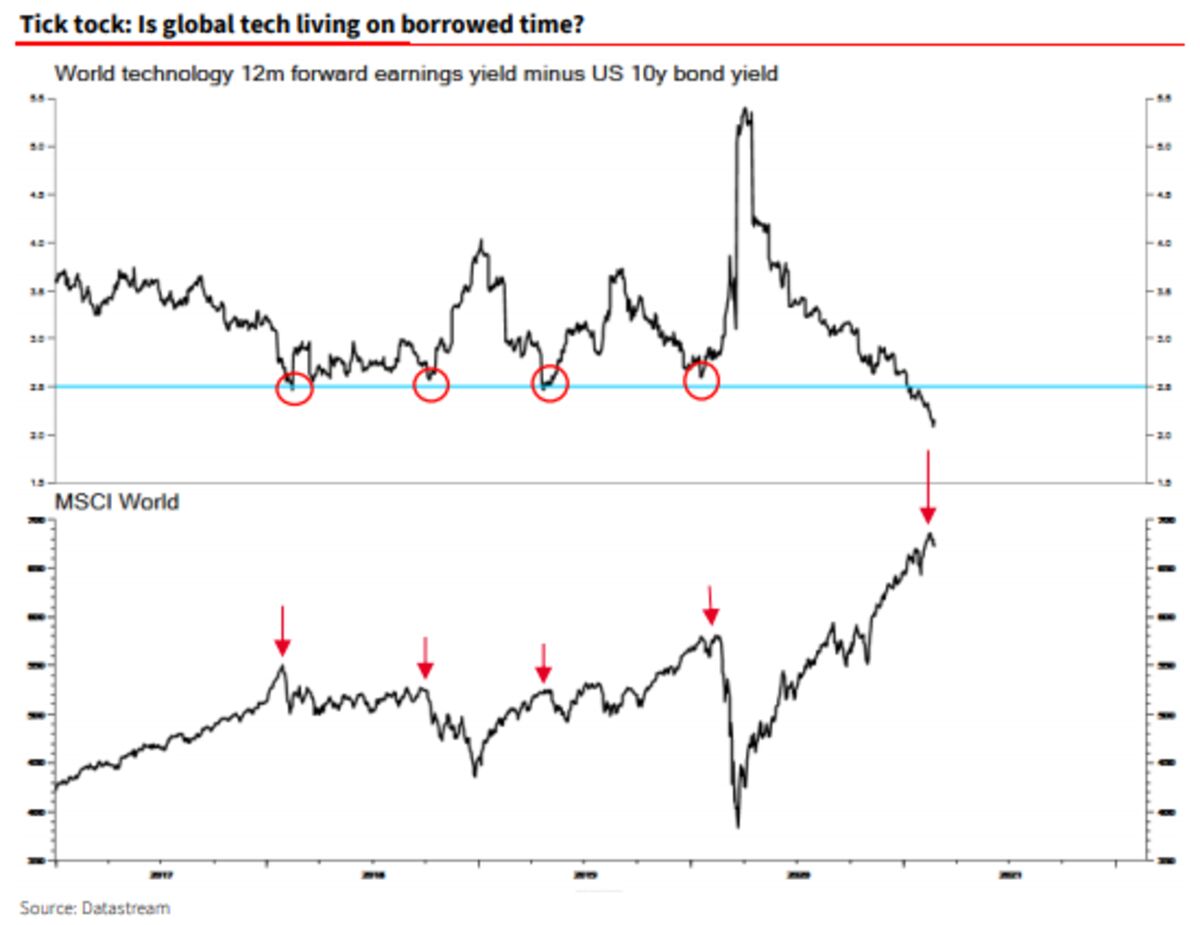

For developed stock markets, the question is whether a spike in bond yields can upset valuations. Tech, which has benefited tremendously from the conditions of the last year, is obviously the source of greatest concern (although to be fair, investors are sitting on fat profits in the sector). SocGen’s Edwards, a well-known bearish commentator, offers this chart, which is an update of research by Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research. Over the last five years, the MSCI World as a whole has shown a tendency to hit a plateau and decline when tech earnings yields drop too far compared to 10-year Treasury yields. That choke point was passed a week ago, and has been followed with this week’s exciting events:

This is decent evidence that bond yields have reached a high enough level to thwart further advances in the stock market. It isn’t yet clear that they would on their own drive a major fall.Opinion. Data. More Data.Get the most important Bloomberg Opinion pieces in one email.EmailBloomberg may send me offers and promotions.Sign UpBy submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

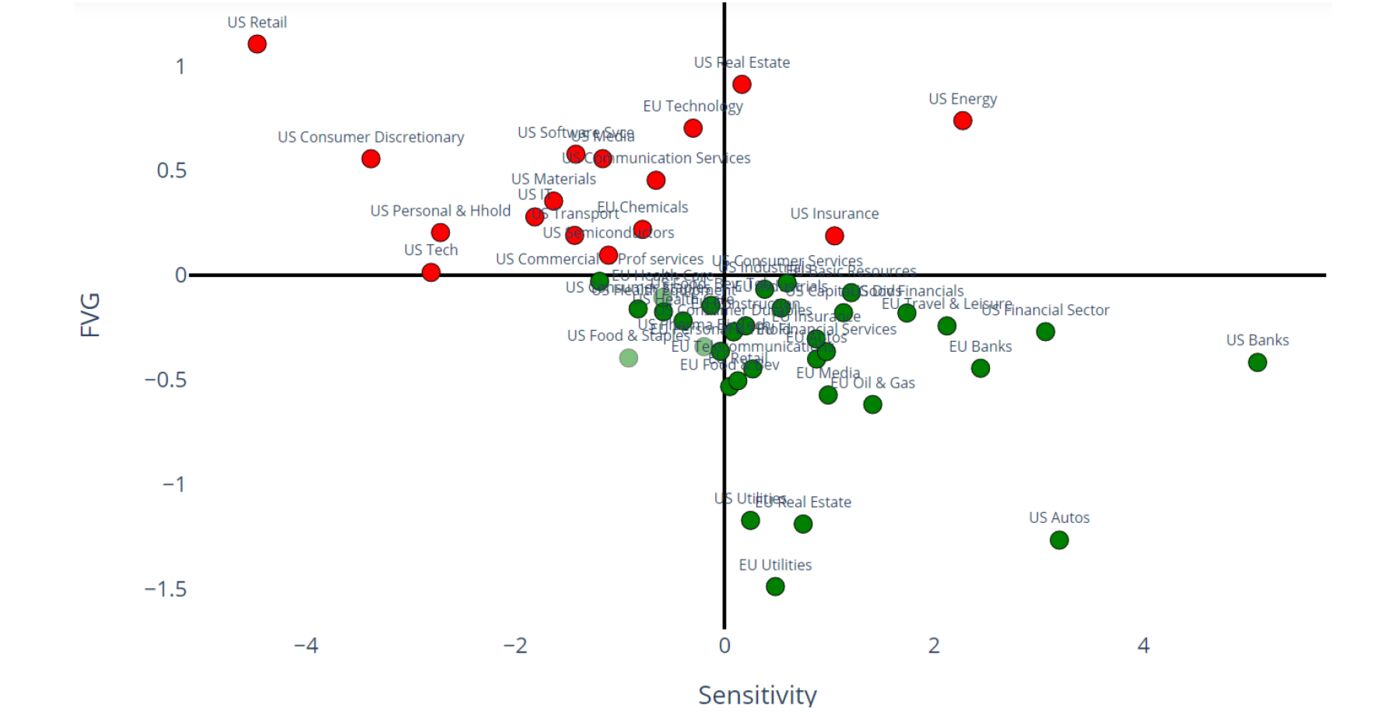

Which sectors are most sensitive? The following work by Quant Insight sheds some interesting light. The vertical axis shows their measure of whether a sector is over-or under-valued compared to current macroeconomic conditions. The lower on the chart, the cheaper. The horizontal axis shows sensitivity to higher yields; the further to the right, the better news high rates will be. You want to avoid anything in the top left quadrant, which is expensive and due to be harmed by higher bond yields.

On this basis, investors might want to fill up on U.S. banks, U.S. automakers, and European utilities. Banks in particular are already doing well. U.S. retail is, by a country mile, the sector you most want to avoid. This chart was produced before Thursday’s excitement but investors seem to be acting in line with its suggestions so far.

Those, I think, are the best guidelines for now. In the longer term, the questions over whether bets on reflation are justified will rest on fascinating and profound issues of macroeconomics (and epidemiology). A true bond tantrum could yet turn into the fixed-income bear market that many of us have been bracing for. For now, this is a big market test of the central banks. It’s their move next.

Survival Tips

I never even had the chance to mention that GameStop Corp. rallied again on Thursday. Plenty of you had suggestions for songs for Redditors who are long GameStop. Try Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying by Gerry and the Pacemakers, We are the Champions by Queen (because there’s “no time for losers”), Eve of Destruction by Barry McGuire, Crash by the Primitives (one of my favorites), and Stop in the Name of Love by the Supremes. Then there’s Debaser by the Pixies, and Working for the Clampdown, Revolution Rock and Should I Stay Or Should I Go by the Clash. There was also a vote for Life on Mars by David Bowie. I think we can infer from that playlist that Points of Return readers are skeptical about the continued buying interest in GameStop. I would also add as a useful warning It’s No Game, also by Bowie.

I hope you survive your Friday, which could be a very interesting one, and have a good weekend.

Treasury Bond Tantrum Is a Big Test of Central Banks’ Mettle – Bloomberg