by John authors via Zerohedge

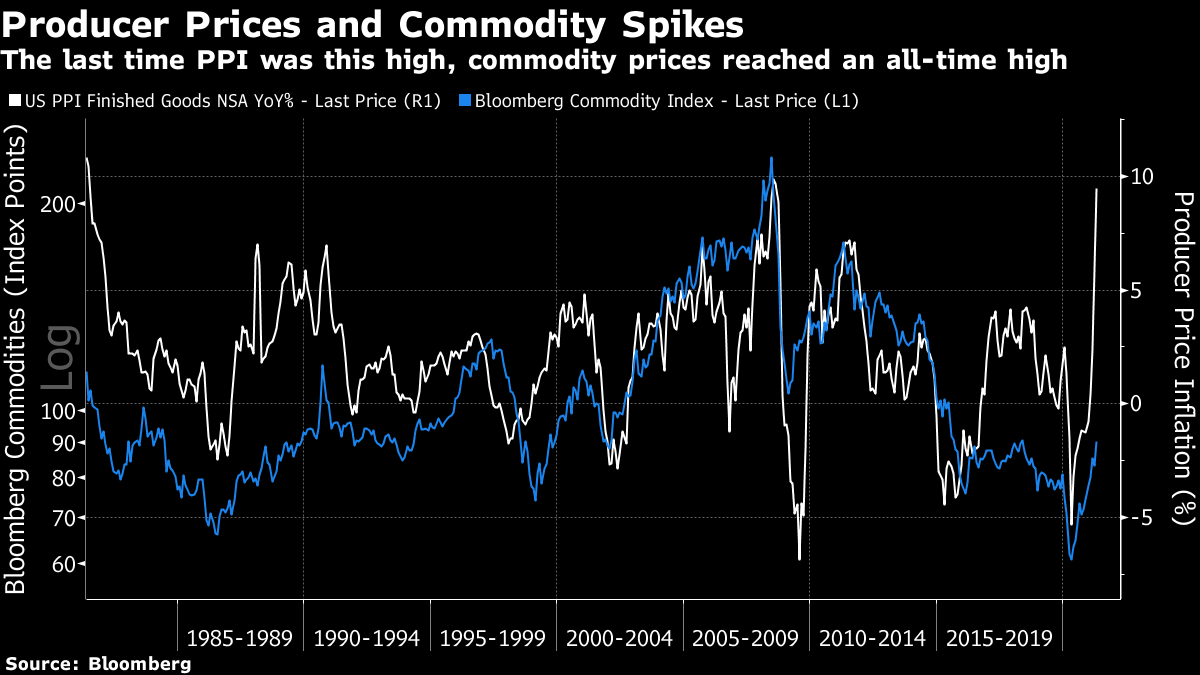

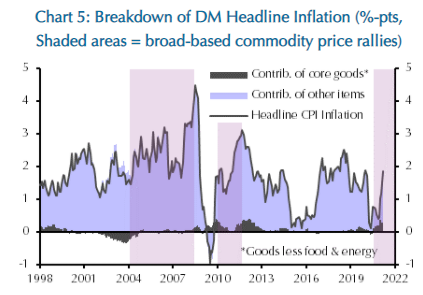

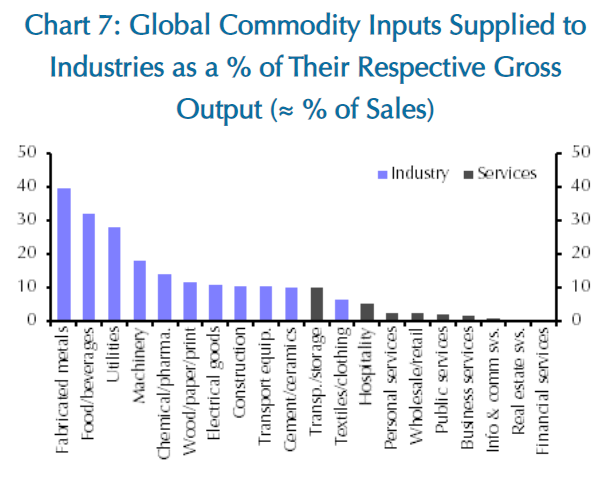

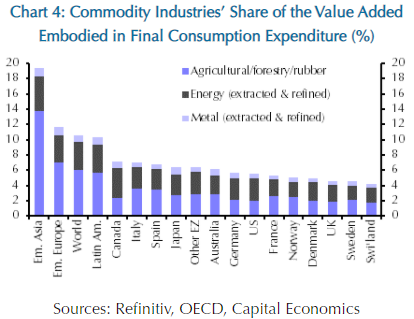

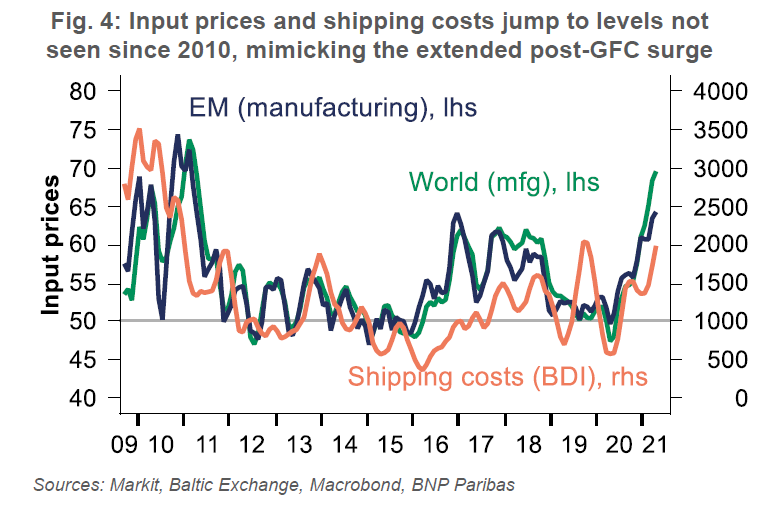

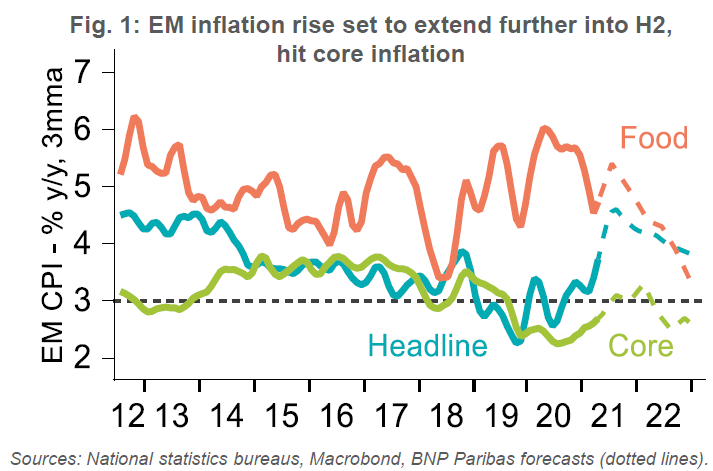

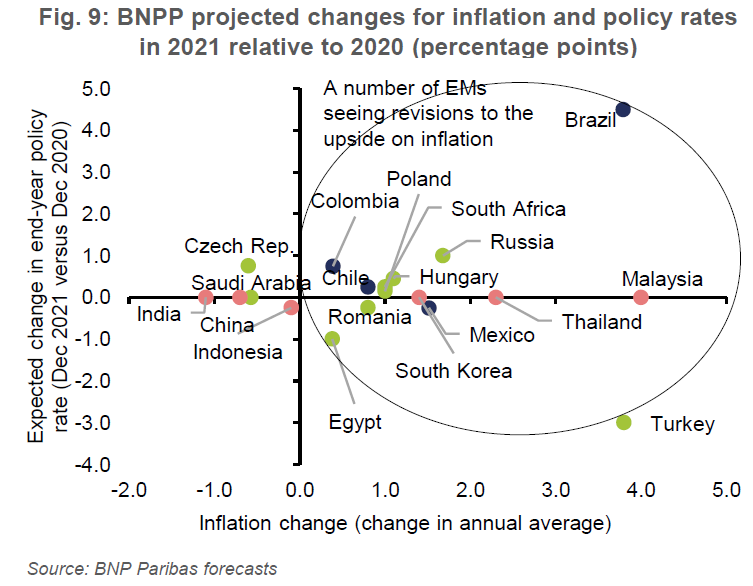

An Emerging Problem Commodity prices are much higher than they have been for a while. Inflation in the U.S. is much higher than it has been for a while. How much are these things related, and what do they portend for the future? There’s certainly some relationship between the commodity complex and companies’ input prices. Producer price inflation provided another unpleasant surprise on Thursday, coming in at its highest in four decades, bar a brief peak in the summer of 2008 ahead of the global financial crisis — which uncoincidentally is when Bloomberg’s broad commodities index hit an all-time high:  The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher: The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher:  The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics: The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics:  But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent: But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent:  One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over: One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over:  This raises the disquieting prospect of social unrest in the emerging world. The spark that lit the Arab Spring revolts of 2011 was a protest in Tunisia over high food prices. As Jason DeSenna Trennert of Strategas Research Partners puts it: Only in a rich nation could one exclude nourishment and staying warm as anything other than “core.” Commodity price inflation can thus be very politically destabilizing, especially in countries without strong and flexible systems of governance. It should be remembered that in the last financial crisis, America experienced both a significant decline in home prices (an event that hadn’t happened since the 1930s) as well as $150 oil simultaneously. Sadly, riots for food in countries like India, Egypt, and Indonesia became commonplace. With America’s twin deficits approaching 20% of GDP, it is difficult to get bullish about the U.S. dollar, especially against commodities and hard assets. In this way, the dollar is, as Treasury Secretary John Connally once said, “our currency and your problem.” So while stronger commodity prices aren’t in themselves too dangerous for inflation in developed countries, they could be profoundly destabilizing in the emerging world. Problems affording food would only exacerbate the pain for the countries like Brazil and particularly India that are currently suffering grievously from the pandemic. Food makes up 29.8% of consumer expenditures in India (and as much as 59% in Nigeria), and only 6.4% in the U.S. Food inflation feeds much more directly into headline inflation in emerging markets, and this will push headline and core inflation upward, according to BNP’s estimates: This raises the disquieting prospect of social unrest in the emerging world. The spark that lit the Arab Spring revolts of 2011 was a protest in Tunisia over high food prices. As Jason DeSenna Trennert of Strategas Research Partners puts it: Only in a rich nation could one exclude nourishment and staying warm as anything other than “core.” Commodity price inflation can thus be very politically destabilizing, especially in countries without strong and flexible systems of governance. It should be remembered that in the last financial crisis, America experienced both a significant decline in home prices (an event that hadn’t happened since the 1930s) as well as $150 oil simultaneously. Sadly, riots for food in countries like India, Egypt, and Indonesia became commonplace. With America’s twin deficits approaching 20% of GDP, it is difficult to get bullish about the U.S. dollar, especially against commodities and hard assets. In this way, the dollar is, as Treasury Secretary John Connally once said, “our currency and your problem.” So while stronger commodity prices aren’t in themselves too dangerous for inflation in developed countries, they could be profoundly destabilizing in the emerging world. Problems affording food would only exacerbate the pain for the countries like Brazil and particularly India that are currently suffering grievously from the pandemic. Food makes up 29.8% of consumer expenditures in India (and as much as 59% in Nigeria), and only 6.4% in the U.S. Food inflation feeds much more directly into headline inflation in emerging markets, and this will push headline and core inflation upward, according to BNP’s estimates:  This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course. This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course.  Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge. Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge. |