By Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen

on July 17, 2020

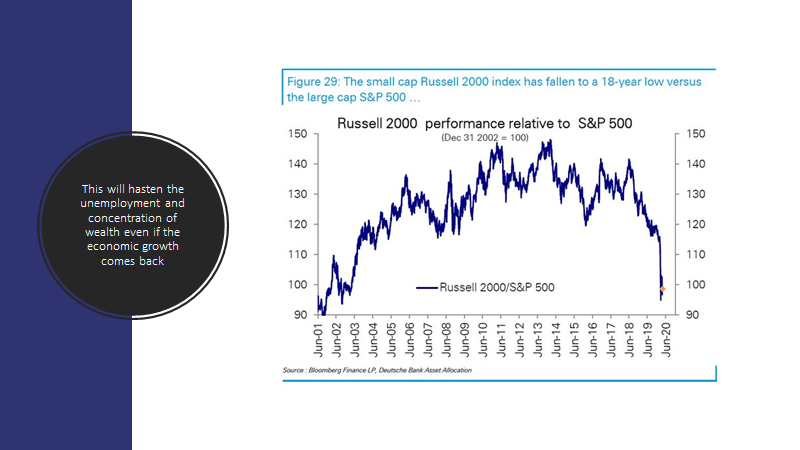

In many respects this recession is unique. Most recessions result from developments inside the economy, but an external shock—the public health crisis—caused this one. To avoid getting sick, people have curtailed working, shopping, and attending school. Whatever the cause, the coronavirus recession, like all recessions, is imposing heavy costs. Many workers have lost jobs and income, and many business owners’ financial survival is at risk. The economy’s extraordinarily rapid decline earlier this year—as well as the sharp but incomplete rebound following the first steps toward reopening—reflect this recession’s unusual source. In addition, the sectors suffering most differ from past recessions. The heaviest blows have fallen on service industries that involve close personal contact (including retail trade, leisure and hospitality, and transportation) rather than, as is more typical, on the housing, capital investment, and durable goods sectors. Lower-paid workers, as well as women and minorities, are over-represented in the most-affected sectors, and thus have borne a disproportionate share of the job and income losses. And, the virus has affected almost every country, with potentially devastating consequences for trade and international investment.

Because this recession is unprecedented in so many ways, forecasting the recovery is difficult. The course of the pandemic itself is by far the most important factor. As long as people fear catching a potentially deadly illness from other people, they will be cautious about resuming normal activities, even after state and local governments lift lockdowns. Thus, controlling the spread of the virus must be the first priority for restoring more-normal levels of economic activity—but, more importantly, for saving possibly tens of thousands of lives. Members of Congress, local leaders, and other policymakers need to do all they can to support testing and contact tracing, medical research, and sufficient hospital capacity, and they must work to ensure that businesses, schools, and public transportation have what they need to operate safely. Both authors of this testimony are serving on state re-opening commissions, which has provided us insight into the substantial challenges to safe re-opening.

If the pandemic comes under better control, economic recovery should follow. However, the pace of the recovery could be slow and uneven, for several reasons. First, in the face of ongoing uncertainty, households and businesses may remain cautious for a time. They may increase saving and reduce spending, hiring, and capital investment. The longer the recession lasts, the greater the damage it will inflict on household and business balance sheets and the longer it will take to repair the damage. Second, the depth of the recession may leave scars—business closures and the deterioration of unemployed workers’ skills—that will affect growth for several years. Third, depending on the course of the virus, some restructuring of the economy may be needed. For example, people and resources will need to be redeployed out of the sectors most damaged by the pandemic, and business operations will need to be reorganized to protect workers and customers. All of that will take time and money. Fiscal and monetary policies must aim to speed the recovery and minimize the recession’s lasting effects.

ACTIONS BY THE FEDERAL RESERVE

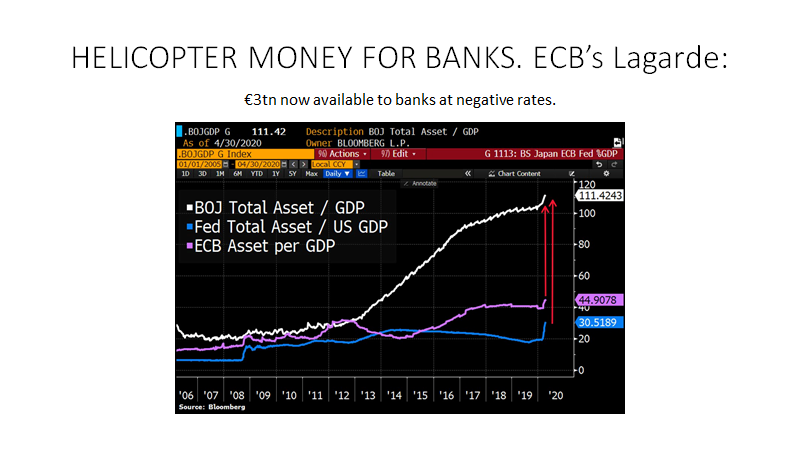

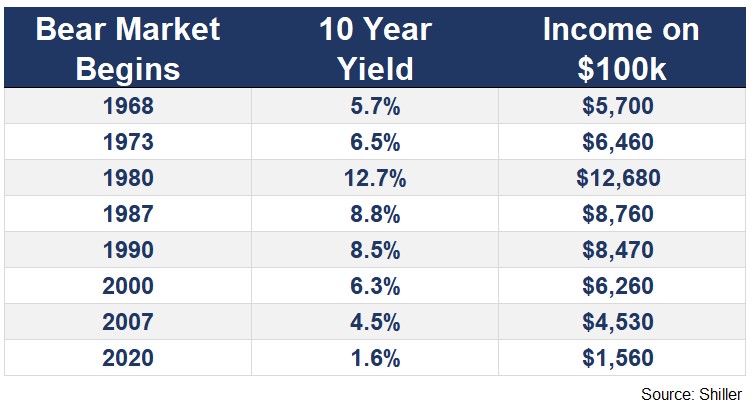

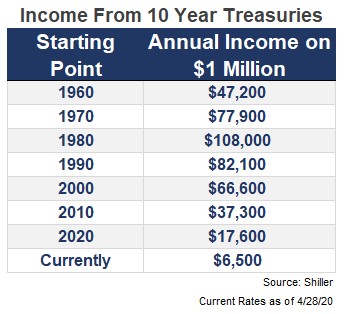

The Federal Reserve has moved swiftly and forcefully in this crisis. It eased monetary policy in March by lowering the federal funds rate, the overnight interest rate on loans between banks, nearly to zero and indicating that it plans to keep rates low for several years. Low interest rates probably had limited economic benefits in the spring. Lockdowns prevented people from spending or working more. However, we expect low rates will spur spending in sectors like housing as the economy reopens. And the Fed may well do more in coming months as re-opening proceeds and as the outlook for inflation, jobs, and growth becomes somewhat clearer. In particular, to maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) likely will provide forward guidance about the economic conditions it would need to see before it considers raising its overnight target rate. And it likely will clarify its plans for further securities purchases (quantitative easing). It is possible, though not certain, that the FOMC will also implement yield-curve control by targeting medium-term interest rates. It could, for example, target two-year rates by announcing its willingness to buy two-year Treasury notes at a fixed yield. The completion of the Fed’s internal review of its tools and framework in coming months will help guide these decisions.

The Fed also has been active beyond monetary policy.

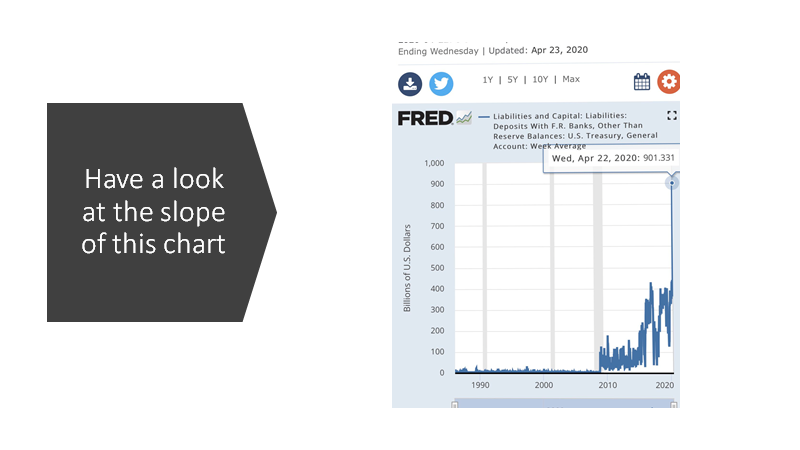

First, the Fed has served as market maker of last resort by acting to stabilize critical financial markets when capital or other regulatory constraints have interfered with normal market-making or arbitrage. The Fed has served this role for repurchase agreements (repos) since September, when intermittent liquidity shortages led to spikes in repo rates. Banks did not provide liquidity to offset these spikes, as they normally would, citing balance sheet limits and other constraints. Because repo markets are critical to the functioning of broader financial and credit markets, as well as for the transmission of monetary policy, the Fed has restored more-normal function in repo markets by conducting large-scale repo operations and by steadily increasing the quantity of reserves in the banking system.

An even larger shock occurred in March, when uncertainty about the pandemic led hedge funds and others to scramble to raise cash by selling longer-term securities. The upsurge in the supply of longer-term securities, including Treasuries, was more than dealers and other market-makers could handle. Key financial markets, including for Treasury securities, experienced substantial volatility. To stabilize these markets, which like the repo market play a critical role in our financial system, the Fed purchased large quantities of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, again serving as market maker of last resort. It also set up a new repo facility to allow foreign official institutions to borrow dollars, using their Treasury reserves as collateral, thus avoiding the need to sell those Treasuries. Although risk and liquidity premiums in these key markets have returned closer to normal, at some point the Fed and the Treasury will need to review why the market-making facilities in place before the pandemic hit did not work more efficiently.

Second, the Fed has served as lender of last resort to the financial system, a classic function of central banks. Banks and other financial intermediaries typically borrow short and lend long—that is, they rely heavily on short-term funding to finance long-term loans and investments. If they lose their short-term funding—because their funders lose confidence or for other reasons—they can be forced to sell their assets in fire sales, restrict credit to customers, and, in extreme cases, become insolvent. Central banks can short-circuit that dangerous dynamic by lending to financial institutions against good collateral, replacing the lost liquidity. In the 2007-2009 crisis, which centered on the financial system and included a global financial panic, the Fed as lender of last resort took many actions to provide liquidity to financial institutions, with the goal of stabilizing the system and preserving the flow of credit to the economy.

Fortunately, the financial system is in much better shape today than in was during the financial crisis. Banks in particular are strong, with much higher levels of capital and liquidity. The Fed nevertheless has once again taken steps to ensure that the financial system has sufficient liquidity. Largely replicating our playbook from the crisis era, the Fed has eased terms on the discount window (which provides short-term loans to banks); re-established the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (which lends to broker-dealers); and established a facility that lends indirectly to money market mutual funds, ensuring that the funds can meet depositor withdrawals. In a novel step, the Fed also created a facility that lends to banks, without recourse, against Payroll Protection Program loans, ensuring that banks have sufficient funds to make those loans.

Under the heading of lender of last resort to the financial system, establishing currency swap lines with fourteen foreign central banks was one of the most important actions the Fed took in the 2007-2009 crisis. The Fed has revived this program. Currency swap lines allow foreign central banks (who assume all the credit risk) to lend dollars to banks in their jurisdictions. The broad availability of dollar liquidity is essential because most global banks do substantial borrowing and lending in dollars, including lending within the United States. The swap lines sustain the flow of dollar credit and reduce volatility in dollar-based markets, to the benefit of the U.S. economy.

Third, the Federal Reserve, with the support of the Congress and the Treasury, has also served during the current crisis as a lender of last resort to the non-financial sector, backstopping key credit markets facing the prospect of severe disruption from the pandemic. To take on this role, the Fed invoked its emergency lending powers under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Since those powers require that the Fed’s lending be well secured, it has had to rely on funds appropriated by the Congress and allocated by the Treasury to cover possible losses. Using these authorities, the Fed revived financial crisis-era facilities to stabilize commercial paper and asset-backed securities markets. Going beyond the financial crisis playbook, the Fed has also added new facilities to lend to corporations and state and local governments and to buy outstanding corporate bonds.

These programs have not extended much credit, so far, but that does not mean they have not succeeded. By establishing the programs, the Fed gave private investors the confidence to re-engage by reassuring them that the government would not allow these critical markets to become dysfunctional. Indeed, the corporate and municipal bond markets largely stabilized after the announcements, before any loans were made. Of course, if these markets seize up again, the Fed’s programs can extend credit.

The Fed also established the Main Street Lending Program to lend (through banks) to medium-sized companies. It is too soon, however, to judge its performance. This program is very different from anything the Fed has attempted before and poses difficult technical challenges. Although the Fed took many public comments while setting up the program, and made substantial changes, questions remain about how many banks and borrowers will participate. The Fed and Treasury may have to further ease terms for borrowers and increase incentives for banks for this program to have the desired effect. Or, the Fed and Treasury could add a new facility, along the lines of funding-for-lending programs run by the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, that simply subsidize banks for making additional loans to qualifying borrowers (for example, businesses below a certain size). That approach leaves the underwriting decision completely with the banks, while the size of the subsidy can be adjusted as needed to achieve the desired level of lending.

Finally, the Fed has also taken actions as a bank regulator—for example, encouraging banks to work with borrowers hobbled by the pandemic. It decided recently, based on stress test results, to bar stock buybacks by banks and to limit—but not eliminate—their dividends. Based on our experience in the global financial crisis, we think the Fed may find it needs to go further. Although banks are currently strong, it is possible the pandemic will so damage the economy that credit losses mount rapidly. For a successful recovery, the banking system must remain strong and able to lend.

Is there more the Fed could do? As we noted, the Fed likely will provide more clarity about its monetary policy plans, and it may need to adjust the terms or borrower eligibility requirements of its various lending facilities. Broadly speaking, though, the Fed’s response has been forceful, forward-looking, and comprehensive. But, as Chair Powell often notes, the Fed’s authorities allow it to lend, not spend. Some households and firms will need subsidies or grants, rather than loans, and spending is, of course, the province of the Congress.

WHAT FISCAL POLICY MIGHT DO

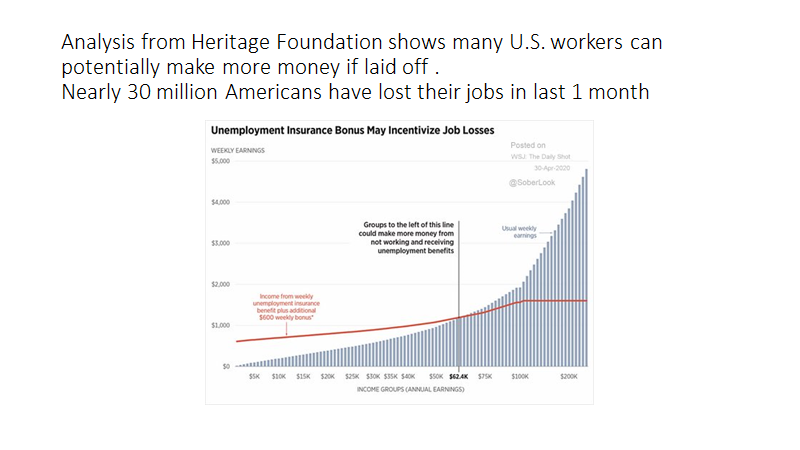

The fiscal response to the pandemic has thus far been quite effective. Enhanced unemployment insurance and the Paycheck Protection Program have helped unemployed workers and their families, together with many businesses, survive the spring shutdowns. The fiscal support for the Fed’s lending programs likely will help preserve credit availability, possibly with only a portion of the allocated funds being spent.

However, some programs authorized by the Congress are ending, and new actions are necessary. Our recommendations for further fiscal action are:

First, Congress should develop a comprehensive plan to support medical research; increase testing, contact tracing and hospital capacity; make available critical supplies; and support state and local efforts to safely open businesses, schools, and public transportation.

Nothing is more important for restoring economic growth than improving public health. Investments in this area are likely to pay off many times over.

Second, with unemployment still very high, enhanced unemployment insurance should be extended, and complementary programs like food stamps should be adequately funded. Unemployment insurance could be restructured to deal with the incentive problems that some have noted, for example, by capping total payments at a fixed percentage of regular income. Rather than making a one-time appropriation, the Congress should create an automatic stabilizer by tying supplementary unemployment insurance and other support programs to the national unemployment rate or state unemployment rates. Under this approach, supplementary support will flow if conditions worsen, without further congressional action, and will automatically decline as conditions improve. This approach would provide people with aid when they most need it and would also help stabilize the economy as a whole by supporting income and stimulating spending automatically when the unemployment rate is high.

Third, Congress should provide substantial support to state and local governments. These governments are on the front line in providing critical services, including first responders, public health, education, and public transportation. State and local governments have been leading the way in designing a safe re-opening of the economy. The enormous loss of revenue from the recession, together with the new responsibilities imposed by the pandemic, has put state and local budgets deeply in the red. With limited capacity to run deficits, these governments will have to lay off workers and limit essential services unless they get federal help. As we learned after the financial crisis, fiscal contraction at the state and local level slows the national economy and offsets the benefits of federal action. To allow state and local governments to continue to provide essential services, and to avoid the recessionary effects of major state and local spending cuts, federal support should be substantial and without overly restrictive conditions on the aid.

Following our advice would further increase the already record-level federal budget deficit. With interest rates extremely low and likely to remain so for some time, we do not believe that concerns about the deficit and debt should prevent the Congress from responding robustly to this emergency. It remains important to use national resources wisely, with well-designed and effective programs. And, at some point, we will have to think through how to ensure the long-run sustainability of federal finances. The top priorities now, however, should be protecting our citizens from the pandemic and pursuing a strong and equitable economic recovery.

My view

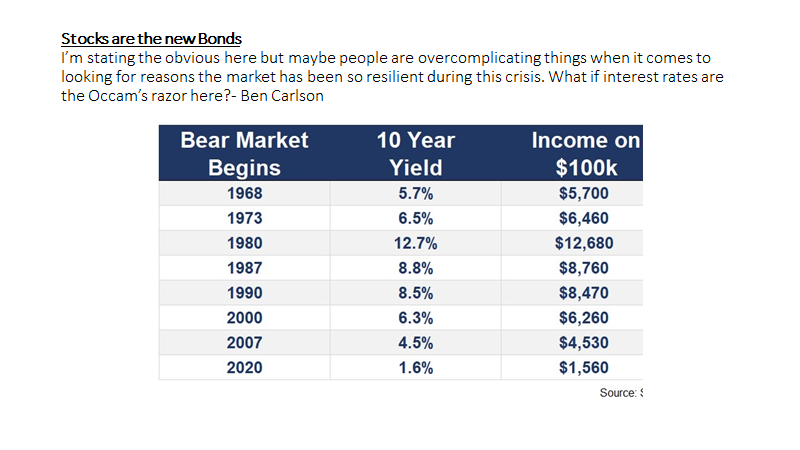

Everything written above in essay will lead to lower dollar and higher inflation along with higher asset prices of securities which will benefit from this strong cocktail of Monetary and fiscal policy with added support from capping of bond yields. US is following the path of post world war II when they capped the bond yields and nominally defaulted on their bond obligations. This way they were also able to reduce their debt burden