By Akash Prakash | 30/07/2019

We have recently seen significant selling of Indian

equities by foreign portfolio investors. In July, the selling has touched

almost $2.5 billion, and is now seems to be accelerating. Consequently, India

has had a very tough year on a relative basis. While the markets globally are

hitting new highs, we are struggling to stay in positive territory. Indian

mid-caps and small-caps continue to get decimated — downdouble digits for the

year. In a ranking of the top 50 equity markets, in terms of performance

year-to-date, we are ranked 43rd. What is surprising is that we are doing

poorly despite what one would think is a very favourable backdrop.

The government that investors wanted has come back with a

much stronger-than-forecast mandate. Oil prices are stable, and seem to be in a

range: The top end of the range does not seem to be a level which will disrupt

our economy. The rupee is very stable, it has, in fact, appreciated post the

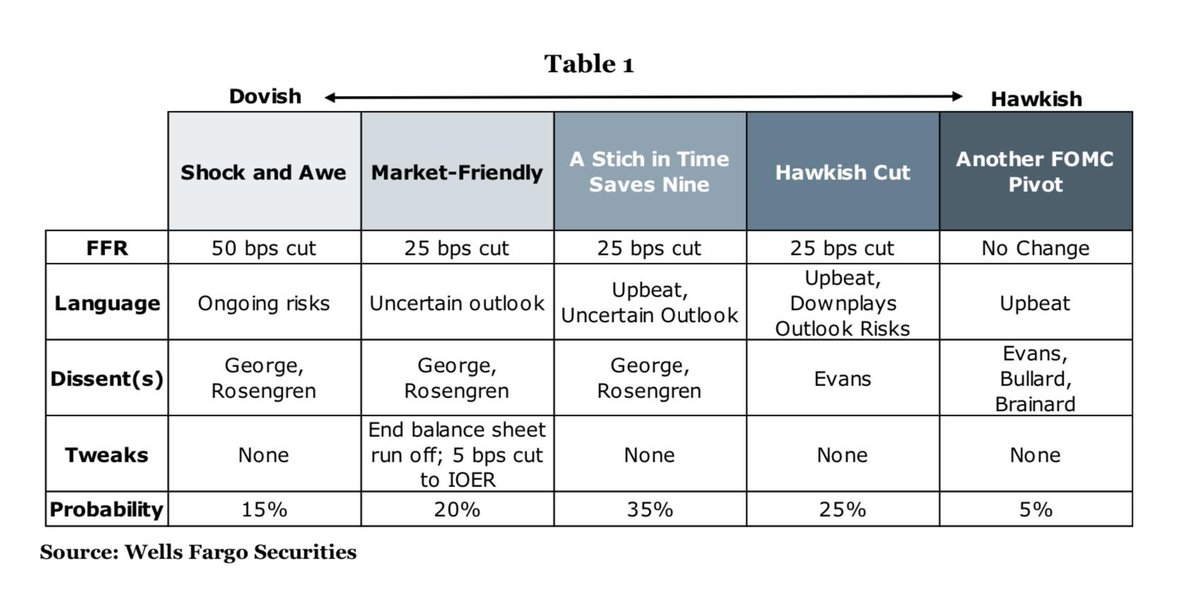

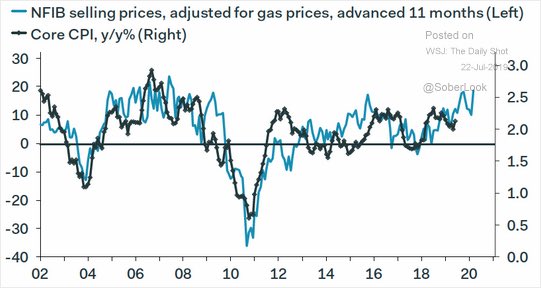

Lok Sabha election. Globally, liquidity is very easy and rates are declining

everywhere. We are on the verge of starting another round of central bank

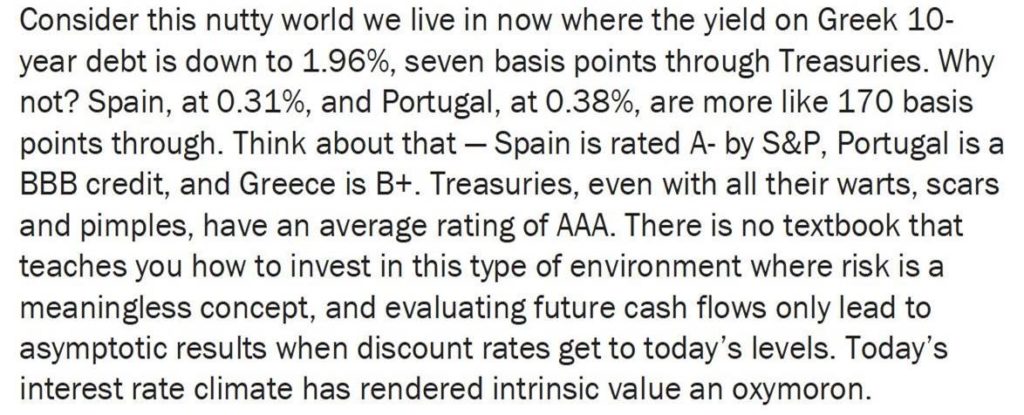

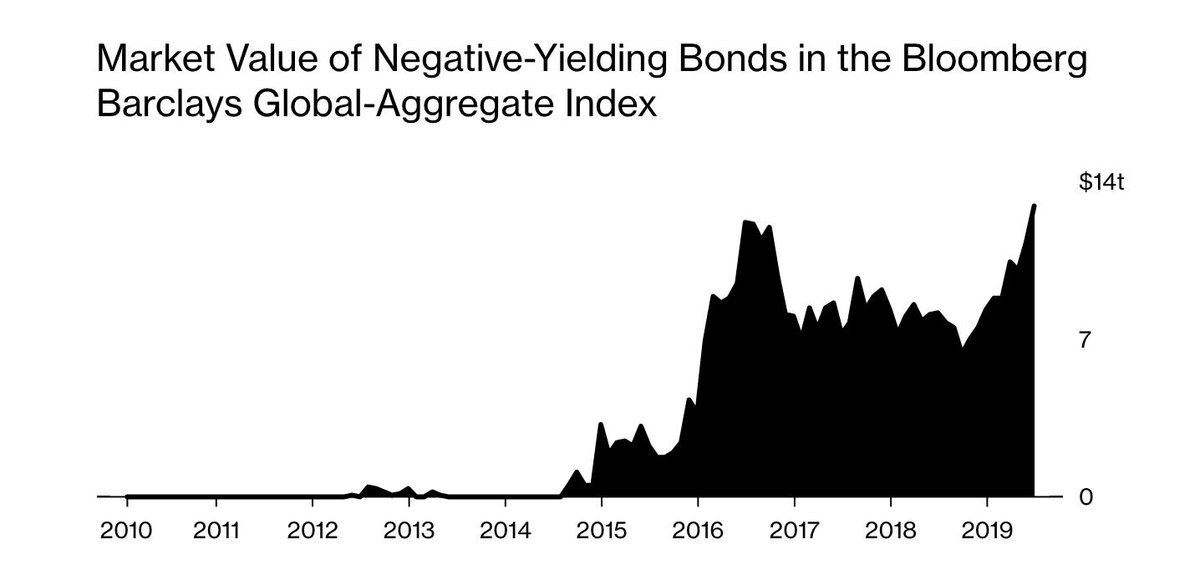

easing, led by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. Amazingly,

nearly 25 per cent of all investment-grade paper globally (both corporate and

government combined) is now trading at negative yields. We are seeing bond

yields for Greece (till recently a basket case) decline to below equivalent US

treasuries. An odd environment!

With yields so low and falling, growth should be at a

premium. India has always been seen as the one economy offering long-term,

secular and sustainable growth. Demographics, low starting point, the catch-up

effect, etc. No one really doubts that India will be the fastest-growing major

economy over the coming decades and definitely grow faster than China. With

growth scarce, India should be bid up. Yet, despite the very favourable

backdrop, the Indian markets are struggling. Why?

There are many reasons, but according to me, these are

the most important ones.

There is total frustration with the lack of corporate

earnings growth. This has been the single-biggest disappointment in Indian

equities over the last eight years. Few people realise that back in 2008, the

share of corporate profits/GDP in India and the US was basically the same at

about 7 per cent. Today, these ratios are near 10 per cent in the US and just

over 2 per cent in India. There has been a total collapse in corporate

profitability in India. We have compounded earnings at less than 5 per cent

over the last eight years. There are various reasons for this earnings

recession. The corporate bank NPA clean up, higher taxes, technological

disruption, economic shocks, no private investment, an overvalued rupee, etc.

Be as it may, the fact remains that no one has been able to forecast the turn

in corporate profitability. No one can explain when and why earnings will

accelerate, beyond the obvious point that corporate profits cannot keep

dropping as a share of GDP. We are already at all-time lows. This has to bottom

out! Given the current weakness in the

economy, this will be another year of an earnings disappointment. The phase of

multiple expansion for our markets is over. Thus, despite bond yields dropping

by almost 100 basis points, the markets are still falling. It is unlikely that

the markets can resume a sustained uptrend in the absence of strong earnings

growth. Most investors, tired of waiting for the earnings inflexion, will now

only increase India allocations once earnings are delivered. On current

earnings, the markets are simply too expensive.

Illustration: Ajay Mohanty

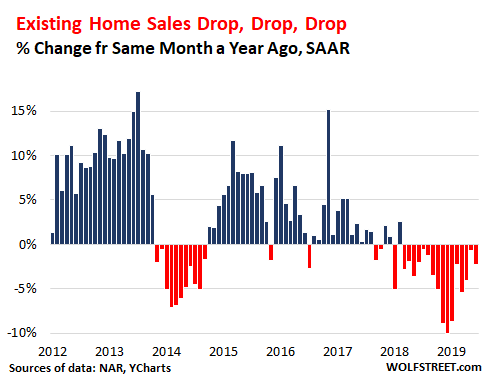

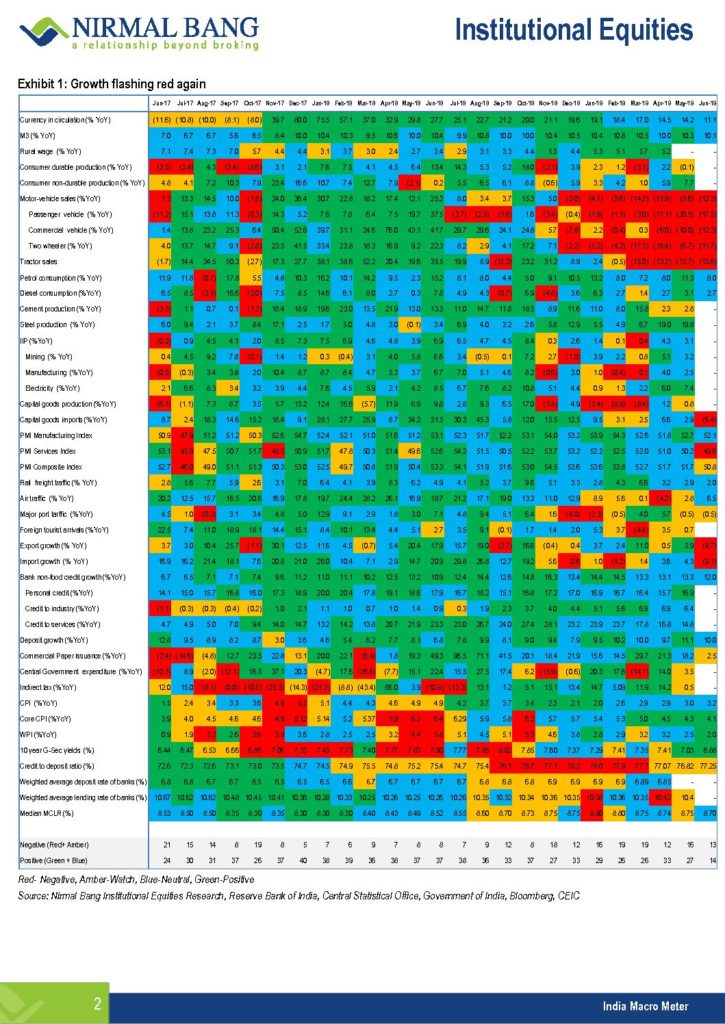

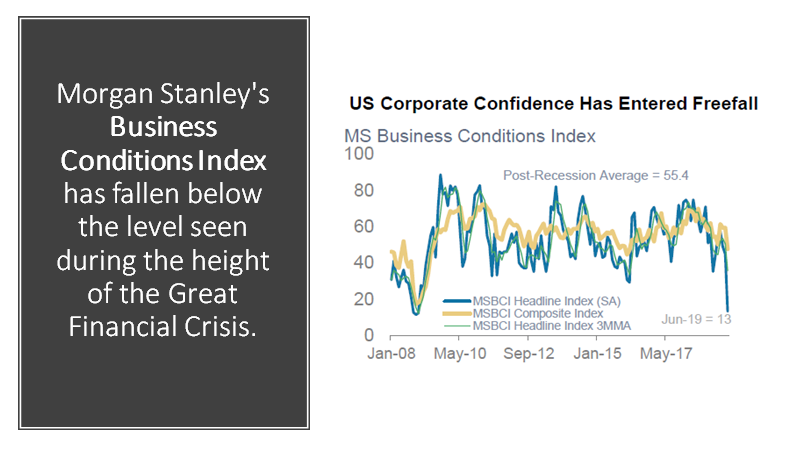

Second, the economy is genuinely weak. I have not seen

corporate sentiment this bad for years. Investors hear a barrage of negative

news when they interact with companies. Animal spirits seem absent. Everyone

just talks of deleveraging and hoarding liquidity, and there is no interest in

setting up new capacity. Demand seems to have hit a wall. Non-banking financial

companies (NBFCs) are in survival mode. Many businesses have no access to

credit. Business confidence gets even

more shaken when states, like Andhra Pradesh, attempt to renegotiate signed

contracts. The government to its credit has tried to lower rates in the

economy, and thus boost consumption and investment. This will help, but in

addition to easing monetary policy, investors would have liked to see more

attempts to push the next generation reforms in land, labour and judiciary, and

make India an easier place to do business. The government, obviously, has an

economic game plan, to get us out of this funk. There has to be a better

articulation of the government’s economic philosophy, priorities and game-plan

for the next five years.

Third, there is also a perception that India may have

moved more to the Left in the economic policy than most investors expected. No

one can deny that we need to spend as much as possible in improving the basic

quality of life of the average Indian. This government won a landslide victory

as it was able to put in place basic infrastructure in rural India, providing

roads, housing, electricity, and cooking gas with very effective execution.

Much more needs to be done. It will need money.

The present approach seems to be to focus on the existing

narrow tax base to get the required resources. This is killing animal spirits.

So is fear. There has undoubtedly been huge abuse of the system by Indian

industrialists. Just look at the NPA crisis. Many should be punished. However,

every large Indian industrialist is not a crook. Ultimately, it will be the

private sector that will create jobs.

We need to find a way to broaden the tax base and be far

more aggressive in monetising government assets to get the money needed. Given

the need for resources in rural India, we cannot afford to give bailouts of

lakhs of crores to PSUs, be it the

banks, Air India or BSNL/MTNL.

In addition, the required returns to make an investment

in India are also rising. Risk premiums will rise when you have judgments like

the recent NCLAT judgment on Essar Steel, or the Andhra fiasco. Taxes also

raise the pre-tax returns needed to justify allocating capital to the country.

If risk premiums rise, the markets have to be cheap enough to deliver the

higher expected pre-tax returns. Public equity markets are currently not cheap

enough.

Sentiment in India is very poor at the moment, among both domestic investors and industrialists. This negativity is now affecting the global investor base. It is unlikely global investors will pre-empt the domestics. We need to see the domestic sentiment turn. For that, we need to see a concerted attempt to make India an easier place to do business. Be it taxes, regulations, reforms, etc.

The writer is with Amansa Capital

The article was originally published in Business Standard

https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/why-are-fpis-selling-119073000001_1.html