In matters of trade and manufacturing, the United States has not been the naive victim of cunning Chinese masterminds. We asked for this.

BY

MICHAEL LIND

MAY 19, 2020

On May 25, 2000, President Bill Clinton hailed the passage of legislation by the House of Representatives establishing permanent normal trade relations with China: “Our administration has negotiated an agreement which will open China’s markets to American products made on American soil, everything from corn to chemicals to computers. Today the House has affirmed that agreement. … We will be exporting, however, more than our products. By this agreement, we will also export more of one of our most cherished values, economic freedom.”

Two decades later, the chickens—or rather, in the case of the novel coronavirus that spread to the world from China, the bats—have come home to roost. In a recent press conference about the pandemic, Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York complained: “We need masks, they’re made in China; we need gowns, they’re made in China; we need face shields, they’re made in China; we need ventilators, they’re made in China. … And these are all like national security issues when you’re in this situation.”

We should not be shocked to discover that many essential items, including critical drugs and personal protective equipment (PPE), that used to be made in the United States and other countries are now virtually monopolized by Chinese producers. That was the plan all along.

Politicians pushing globalization like Clinton may have told the public that the purpose of NAFTA and of China’s admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) was to open the closed markets of Mexico and China to “American products made on American soil, everything from corn to chemicals to computers.” But U.S. multinationals and their lobbyists 20 years ago knew that was not true. Their goal from the beginning was to transfer the production of many products from American soil to Mexican soil or Chinese soil, to take advantage of foreign low-wage, nonunion labor, and in some cases foreign government subsidies and other favors. Ross Perot was right about the motives of his fellow American corporate executives in supporting globalization.

The strategy of enacting trade treaties to make it easier for U.S. corporations to offshore industrial production to foreign cheap-labor pools was sold by Clinton and others to the American public on the basis of two implicit promises. First, it was assumed that the Western factory workers who would be replaced by poorly paid, unfree Chinese workers would find better-paying and more prestigious jobs in a new, postindustrial “knowledge economy.” Second, it was assumed that the Chinese regime would agree to the role assigned to it of low-value-added producer in a neocolonial global economic hierarchy led by the United States, European Union, and Japan. To put it another way, China had to consent to be a much bigger Mexico, rather than a much bigger Taiwan.

Neither of the promises made by those like Clinton who promoted deep economic integration between the United States and China two decades ago have been fulfilled.

The small number of well-paying tech jobs in the U.S. economy has not compensated for the number of manufacturing jobs that have been destroyed. A substantial percentage of those well-paying tech jobs have gone not to displaced former manufacturing workers who have been retrained to work in “the knowledge economy” but to foreign nationals and immigrants, a disproportionate number of whom have been nonimmigrant indentured servants from India working in the U.S. on H-1B visas.

The devastation of industrial regions by imports from China, often made by exploited Chinese workers for Western corporations, is correlated in the United States and Europe with electoral support for nationalist and populist politicians and parties. The Midwestern Rust Belt gave Donald Trump an electoral college advantage in 2016, and the British Labour Party’s Red Wall in the north of England cracked during the Brexit vote in 2016 and crumbled amid the resounding victory of Boris Johnson’s Conservatives in 2019.

The second implicit promise made by the cheerful advocates of deep Sino-American economic integration like Bill Clinton was that China would accept a neocolonial division of labor in which the United States and Europe and the advanced capitalist states of East Asia would specialize in high-end, high-wage “knowledge work,” while offshoring low-value-added manufacturing to unfree and poorly paid Chinese workers. China, it was hoped, would be to the West what Mexico with its maquiladoras in recent decades has been to the United States—a pool of poorly paid, docile labor for multinational corporations, assembling imported components in goods in export-processing zones for reexport to Western consumer markets.

But the leaders of China, not unreasonably, are not content for their country to be the low-wage sweatshop of the world, the unstated role assigned to it by Western policymakers in the 1990s. China’s rulers want China to compete in high-value-added industries and technological innovation as well. These are not inherently sinister ambitions. China is governed by an authoritarian state, but so were Taiwan and South Korea until late in the 20th century, while Japan was a de facto one-party state run for nearly half a century by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was neither liberal nor democratic.

Even a democratic, multiparty Chinese government that sponsored liberalizing social reforms would probably continue a version of the successful state sponsorship of industrial modernization in order to catch up with, if not surpass, the U.S. and other nations that developed earlier. That is what China’s neighbors, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, all did following WWII. Indeed, when the United States and Imperial Germany were striving to catch up with industrial Britain in the 19th century, they employed many of the same techniques of national developmentalism, including protective tariffs and, in America’s case, toleration of theft of foreign intellectual property. (British authors visiting the U.S. often discovered that pirated editions of their works were as easy to purchase then as pirated Hollywood movies and knockoffs of Western brands are to obtain in Asia today.)

The question, then, is not why China pursued its own variant of classic state-sponsored industrial development policies in its own interest. The question is why the U.S. establishment did not retaliate against China’s policies for so long, given the damage they have done to American manufacturing and its workforce.

The answer is simple. American politics and policy are disproportionately shaped by the rich, and many, perhaps most, rich Americans can do quite well for themselves and their families without the existence of any U.S. manufacturing base at all.

We are taught to speak about “capitalism” as though it is a single system But industrial capitalism is merely one kind of capitalism among others, including finance capitalism, commercial capitalism, real estate capitalism, and commodity capitalism. In different countries, different kinds of capitalism are favored by different regimes.

Recognizing that there are, in fact, different kinds of capitalism, not only among nations but within them, allows us to understand that the different variants of profit-seeking can interact in kaleidoscopic ways. National economies can compete with other national economies or they can complement them.

The United States could decline into a deindustrialized, English-speaking version of a Latin American republic, specializing in commodities, real estate, tourism, and perhaps transnational tax evasion.

America’s economic elite is made up mostly of individuals and institutions whose sectors complement state-sponsored Chinese industries instead of competing with them. It is pointless to try to persuade these influential Americans that they have a personal, financial stake in manufacturing on American soil. They know that they do not.

The business model of Silicon Valley is to invent something and let the dirty physical work of building it be done by serfs in other countries, while royalties flow to a small number of rentiers in the United States. Nor has partial U.S. deindustrialization been a problem for American financiers enjoying the low interest rates made possible in part by Chinese financial policies in the service of Chinese manufacturing exports. American pharma companies are content to allow China to dominate chemical and drug supply chains, American real estate developers lure Chinese investors with EB-5 visas to take part in downtown construction projects, American agribusinesses benefit from selling soybeans and pork to Chinese consumers, and American movie studios and sports leagues hope to pad their profits by breaking into the lucrative China market.

For their part, many once-great American manufacturing companies have become multinationals, setting up supply chains in China and other places with low-wage, unfree labor, while sheltering their profits from taxation by the United States in overseas tax havens like Ireland and the Cayman Islands and Panama. Many of these so-called “original equipment manufacturers” (OEMs)—companies that outsource and offshore most of their manufacturing—are engaged as much in trade, marketing, and consumer finance as they are in actually making things.

We should not be surprised that multinational firms, given the choice, typically prefer to maximize profits by a strategy of driving down labor costs, replacing well-paid workers with poorly paid workers in other countries, rather than by becoming more productive through replacing or augmenting expensive labor with innovative machinery and software in their home countries. Labor-saving technological innovation to keep production at home is hard. Finding cheaper labor in another country is easy.

In short, the United States has not been the naive victim of cunning Chinese masterminds. On the contrary, in the last generation many members of America’s elite have sought to get rich personally by selling or renting out America’s crown jewels—intellectual property, manufacturing capacity, high-end real estate, even university resources—to the elite of another country.

A century ago, many British investors did well from overseas investments in factories in the American Midwest and the German Ruhr, even as products from protectionist America and protectionist Germany displaced free-trading Britain’s own unprotected manufacturing industry in Britain’s own markets. By building up China’s economy at the expense of ours, America’s 21st-century overclass is merely following the example of the British elite, which, like a bankrupt aristocrat marrying a foreign plutocrat’s daughter, sells its steel plants to Indian tycoons and state-backed Chinese firms, sells London mansions to Russian gangsters and Arab aristocrats, and sells university diplomas to foreign students including Americans and Chinese.

When asked whether the rapid dismantling, in a few decades, of much of an industrial base built up painstakingly over two centuries has been bad for the United States, the typical reply by members of the U.S. establishment is an incoherent word salad of messianic liberal ideology and neoclassical economics. We are fighting global poverty by employing Chinese factory workers for a pittance! Don’t you understand Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage?

Some of the profits made by rich Americans in the modern China trade are recycled as money flowing to universities, think tanks, and the news media. The denizens of these institutions tend to be smart and smart people know who butters their bread. Predictably, intellectuals and journalists who benefit from the largesse of American capitalists with interests in China are inclined to please their rich donors by characterizing critics of U.S. China policy as xenophobes who hate Asian people or else ignorant fools who do not understand that, according to this or that letter in The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times signed by 1,000 or 10,000 or 100,000 economics professors, free trade always magically benefits all sides everywhere all at once.

All of this idealistic verbiage about the wonders of free trade and the moral imperative of ending global poverty by replacing American workers with foreign workers cannot muffle the click of cash registers.

The dangerous dependence of the United States and other advanced industrial democracies on China for basic medical supplies has been exposed by the current pandemic. The U.S. and other industrial democracies now confront a stark choice. Western countries can continue to cede what remains of their manufacturing base and even control of their telecommunications and drone infrastructure to Beijing and specialize as suppliers of technological innovation, higher education, agriculture, minerals, real estate, and entertainment to industrial China. Or they can view Western economies as competitors of the Chinese economy, not complements to it, and act accordingly.

Rejection of the view that our economy should compete with, rather than complement, that of China in key sectors does not require us to endorse demagogic claims that the Chinese regime is a crusading ideological enemy hell-bent on world domination like Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. On the contrary, a strategy of U.S. industrial independence informed by sober realism would entail recognition of the legitimate interest of China, under any regime, in building up its own advanced industries—on the condition that China in return recognize America’s legitimate interests in preserving its own domestic supply chains in the same key industrial sectors.

Econ 101 to the contrary, the purpose of international trade should not be to maximize the well-being of global consumers by means of a global division of labor among countries that specialize in different industries, but to allow sovereign states to pursue industrial policies in their own long-term interest, as they define it. Trade, investment, and immigration policies should be subservient to national industrial strategy. The purpose of trade negotiations should be the modest one of reconciling different, clashing, and equally legitimate national industrial policies in a mutually acceptable way.

National industrial policies are like national militaries—essential local public goods provided by a sovereign government to a particular people. The model for trade negotiations should be bilateral and multilateral arms control, which are based on the premise that all parties have a perpetual right to their own militaries, rather than global disarmament, which seeks the utopian goal of eliminating all militaries everywhere.

All modern economies are mixed economies, with public sectors and private sectors, and all modern trade should be mixed trade, with wholly protected sectors, partly protected sectors with managed trade, and sectors in which free trade is not dangerous and is therefore allowed. In a post-neoliberal world, it would be understood that the legitimate self-interest of sovereign nations and blocs inevitably imposes strict limits on the acceptable flow of goods, money, and labor across borders. Institutions which limit the right of sovereign states to promote their own national industries as they see fit, like the World Trade Organization (WTO), should be reformed or abolished.

All major countries like the United States, China, and India and all major trading blocs like the EU should insist on having their own permanent domestic supply chains in medicine, medical gear, machine tools, aircraft and drones, automobiles, consumer electronics, telecommunications equipment, and other key sectors. They should have the right to create or protect these essential industries by any means they choose, at the expense of free trade and free investment if necessary.

If China and India want to have their own national aerospace industries in addition to the United States and European Union, more power to them—as long as the United States and European Union can intervene to preserve their own national aerospace supply chains on their own soil employing their own workers. If this approach means accepting that Western-based aerospace firms like Boeing and Airbus cannot hope to enjoy a permanent shared monopoly in global markets for large jets, well, too bad. Boeing and Airbus cannot claim in good times to be post-national global corporations to justify offshoring policies and then claim in bad times to be national champions when they need bailouts.

The alternative—deepening the complementarity among China’s industrial and America’s postindustrial economies—would be much worse for the United States. The same American overclass whose members have profited the most from transferring national assets to China in the last generation has also been far more insulated from the effects of imports from China, both manufactured goods and viruses. The United States, which has always had features of a Third World country as well as a First World country, could decline into a deindustrialized, English-speaking version of a Latin American republic, specializing in commodities, real estate, tourism, and perhaps transnational tax evasion, with decayed factories scattered across the continent and a nepotistic rentier oligarchy clustered in a few big coastal cities.

It would be ironic as well as tragic if the strategy of Sino-American economic integration which American elites in the 1990s hoped would turn China into another Mexico for the United States ends up turning the United States into another Mexico for China.

The China Question – Tablet Magazine

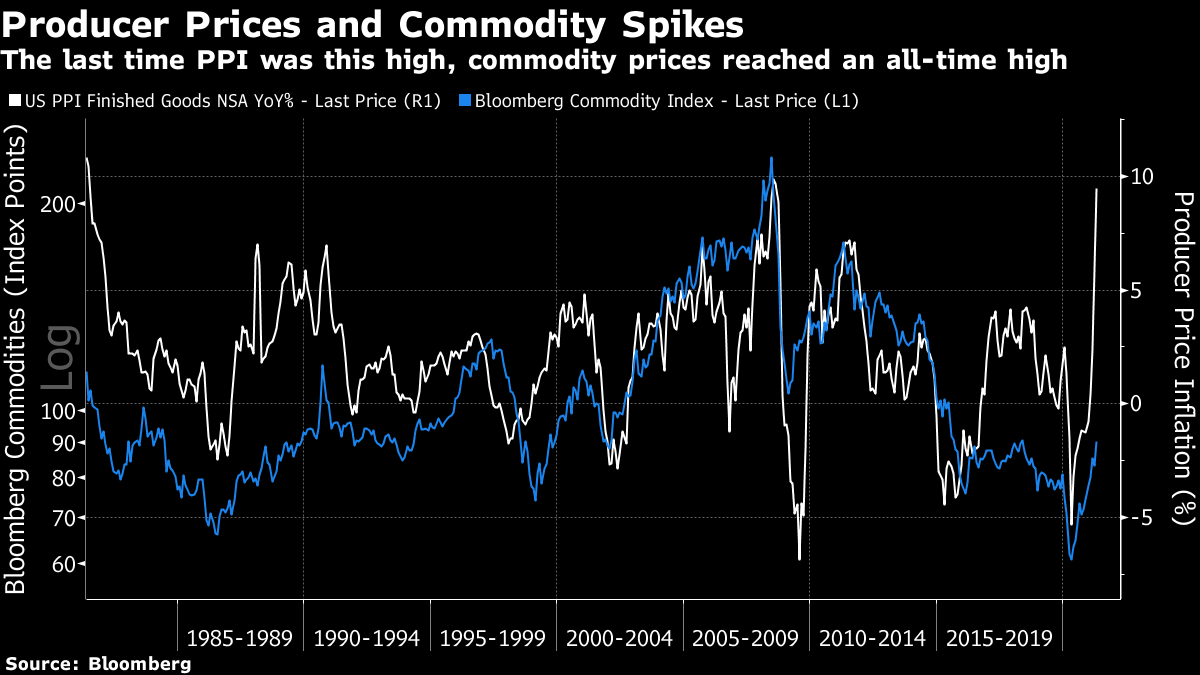

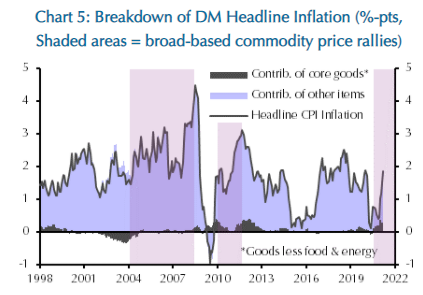

The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher:

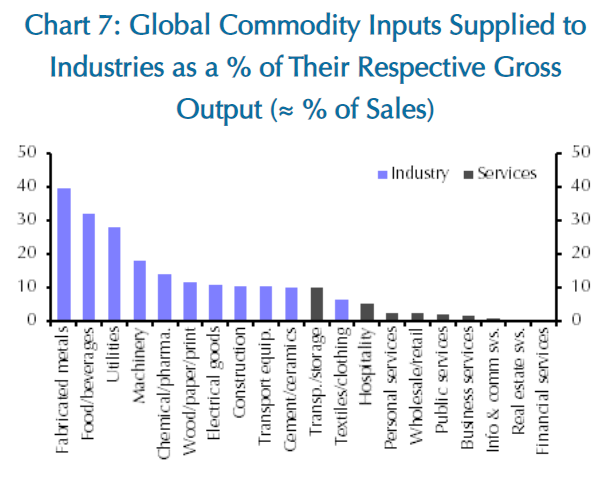

The 2008 price spike was driven by oil. There is nothing like such pressure now, although the latest 12-month increase for the Bloomberg index, at 48.4%, is the highest in four decades. However, in developed markets at least, the contribution of core goods — excluding oil and agricultural products — to inflation isn’t very significant. The following chart, from London’s Capital Economics Ltd., shows that the contribution is much lower than it was about 10 years ago, when the level of commodity prices was higher:  The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics:

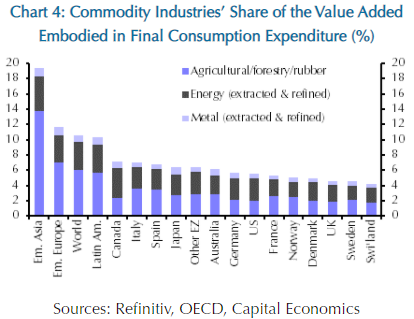

The steadily changing nature of the economy also makes basic commodity prices less important, They still matter greatly for the metals industry (obviously), and food business and utilities, but their contribution to the services that now dominate the economy is negligible. This chart is also from Capital Economics:  But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent:

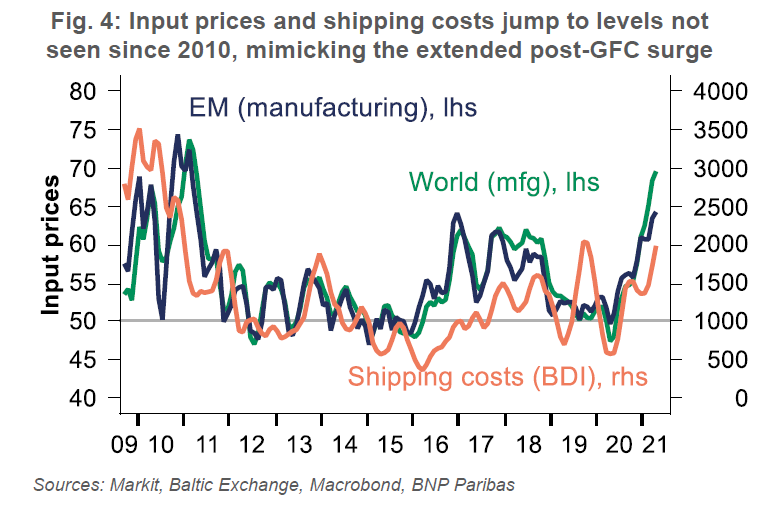

But while commodity inflation is no longer of such direct import to the developed world, it still has serious effects on emerging economies. When we look at commodities’ share of final consumption, we find that emerging Asia is far more exposed to commodity prices than Europe and North America. Sub-Saharan Africa, not shown here, is even more commodity-dependent:  One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over:

One further problem for the developing world is that rises in commodity prices tend to be sustained, and move in waves. BNP Paribas SA shows that input prices (as taken from the Markit ISM surveys) are rising sharply in emerging markets. The last time they reached these levels, in the wake of the GFC, prices stayed high for a couple of years before settling into the prolonged bear market that is now over:  This raises the disquieting prospect of

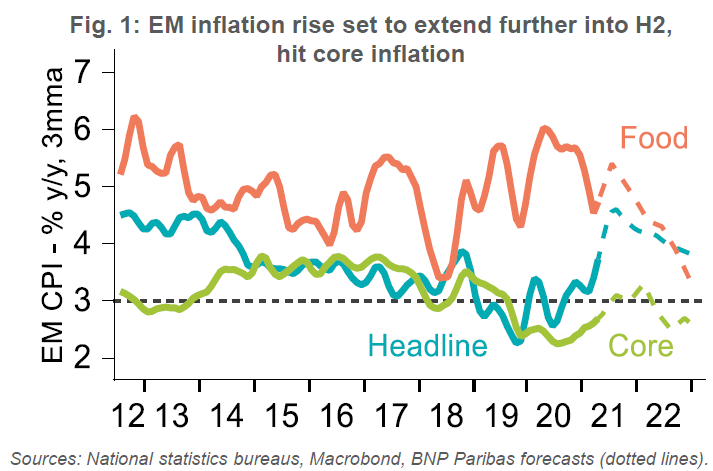

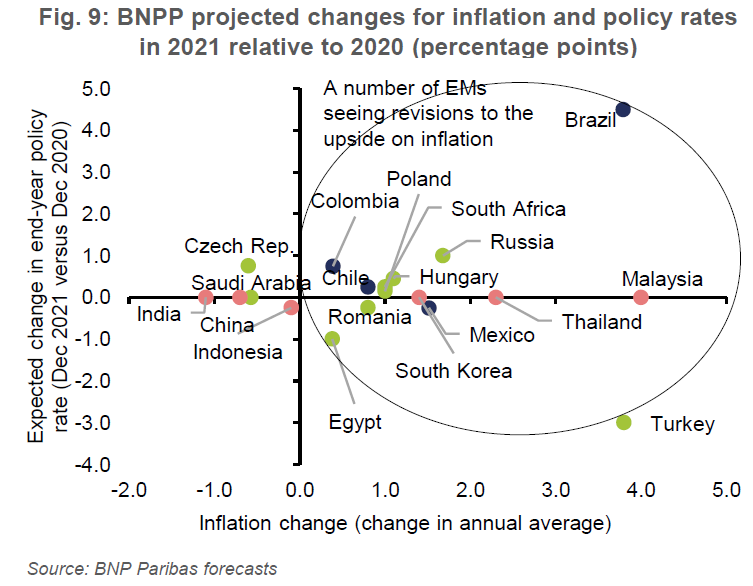

This raises the disquieting prospect of  This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course.

This could in turn force a number of countries into interest rate hikes at a point when their economies wouldn’t otherwise be ready for them. Brazil in particular looks set for sharp tightening, as well as increased inflation. In much of the rest of the developing world, BNP Paribas shows, the expectation is that countries will endure a rise in inflation without adjusting monetary policy from their previously planned course.  Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge.

Rising interest rates can be almost as unpopular as food price inflation in the developing world, particularly in a time of pandemics, so central banks will naturally try to avoid them. But this is where the most difficult inflationary challenges lie at present. In the developed world, the uptick in inflation might still prove a transitory quirk caused by reopening. In the emerging world, food price inflation is already forming a serious social and economic challenge.