Let’s embark on a journey that began in the year 2000, one that was greeted with joy, now is shunned by investors and called a ruin. A process called Fracking was discovered in mid 2000s with which US created Shale wells and once a country hugely dependent on crude oil imports plummeted to lowest level of crude imports since 1967. Federal Reserve’s decision to keep interest rates about zero percent in 2007 further bolstered the shale business and lured investors with capital in exchange of promising lucrative returns and stable growth. How could they have known that the energy with which shale boomed could also be doomed!

In 2014, oil prices crashed, there was heavy crude sell – off, embedded options on oil prices which were considered safe resort were no safer and they kept spiralling down until February 2016! Shale producers revamped the production at the expense of their longevity, depleted their long term reserves to maximise their current production and now are under the gun by investors. Even though oil prices rose considerably from its lowest in 2016, Capex remains 25 – 35% lower than what it had in 2012 – 2014. According to Dealogic, companies raised about $22bn from equity and debt financing in 2018, less than half the total in 2016 and almost one third of what they raised in 2012.

Shale industry has had negative cash flows since its beginning and as Denning pointed out it has not posted a return on capital above 10 percent any year since 2006 and IEA estimated cumulative negative free cash flow of over $200bn between 2010 – 2014. Many however, overlooked the fact that McLean highlighted in the book ‘Saudi America’ which said, “The ability of oil and gas exploration companies to tap into underground formations is a result not only of technology but just as important of cheap capital. The fracking boom has been fuelled mostly by overheated investment capital, not by cash flow.” WSJ phrased this as, “A feature of shale, not a bug.”

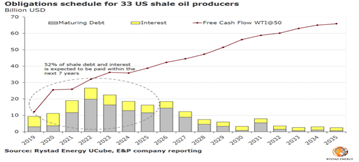

McLean further indicated that the very structure of shale business had fault lines. “For all the hoopla about the surge in US oil and gas production from fracking, most people overlook an important feature of the boom: The average shale well produces most of its oil or gas in first two years. That means oil companies must keep drilling new wells to keep production steady. To maintain production of 1 million barrels per day, shale requires up to 2,500 wells while production in Iraq can do it with fewer than 100.” Now, shale companies are under the radar and investors demand them to either be self – supporting or to return their invested cash. They find themselves straddled with depleting reserves and stalling gains from shale exploration productivity. Rystad Energy Senior Analyst Alisa Lukash said in her statements that, “E&P struggles to please equity investors and reduce leverage ratios simultaneously. Despite a significant deleverage last year, estimated 2019 free cash flow barely covers operator obligations, putting E&Ps on thin ice as future dividend payments in question.” Rystad finds that over half of the total debt pile for 33 companies it analysed is due within next seven years. Ultimately the industry will have to erase $4bn promised dividend payments.

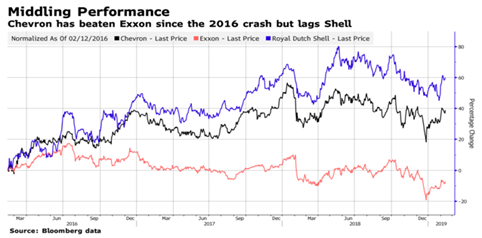

Amid dark clouds, the two big players ExxonMobil and Chevron remain optimistic. ExxonMobil recently said that its oil and gas reserves rose nearly 23 percent last year driven mainly by increases from holdings in US Shale (Permian basin), offshore Guyana and Brazil. US crude oil production has hit a milestone in August when it exceeded 11 million barrels for the first time according to Federal Energy Information Administration. When the survival of small shale companies is on the edge, many investors argue that M&A activity where the big multinationals absorb small shale companies could be profitable for everyone with big companies keeping more shale basins and small with continued operations.

West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures hit the highest level in February since November with a barrel for March delivery at $55.93. The rally is driven by political uncertainty, OPEC cuts and worries about slowdown in shale production is seeing a rush out from short positions. Hedge funds abandoned their short selling bets in January after oil had its best month in three years.

I would end this journey by quoting McLean, “Even today, it is unclear if we look back and see fracking as the beginning of a huge and lasting shift or if we wistfully realizing that what we thought was transformative was merely a moment in time.”

with Inputs from Apra Sharma

Two words – debt refinancing.

Ps: would love to look at rystad energy report. At current rate of production and growth, thought reserves would start to be exhausted in 8-10 years. But they seem to be projecting very large jump in cash flows even 10years out – how?