By Doug Noland via creditbubble buletein

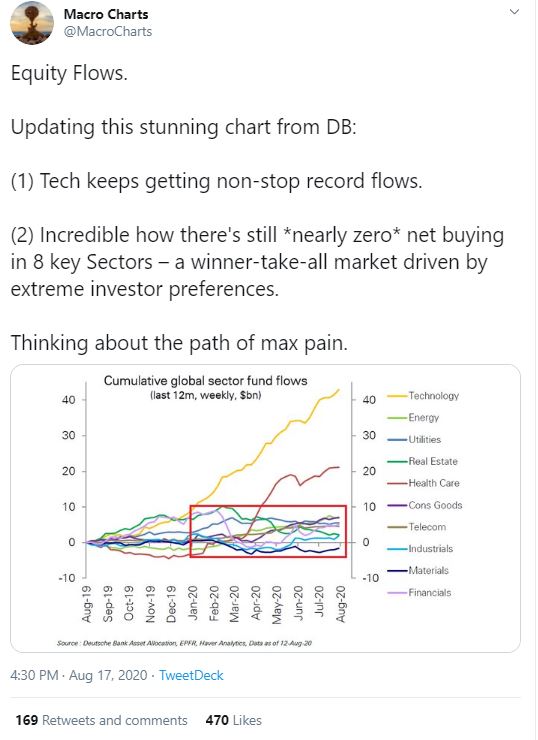

The Nasdaq100 (NDX) jumped another 3.5% this week, increasing 2020 gains to 32.3%. Amazon gained 4.3% during the week, boosting y-t-d gains to 77.8% – and market capitalization to $1.626 TN. Apple surged 8.2% this week, increasing 2020 gains to 69.4%. Apple’s market capitalization ended the week at a world-beating $2.127 TN. Microsoft rose 2.0% (up 35.1% y-t-d, mkt cap $1.612 TN). Google rose 4.8% (18.2%, $1.073 TN), and Facebook gained 2.2% (30.1%, $761bn). The NDX now trades with a price-to-earnings ratio of 37.4.

This era will be analyzed and debated for decades to come – if not much longer. Market Bubbles, over-indebtedness, inequality, financial instability and economic maladjustment – festering for years – can no longer be disregarded as cyclical phenomena. Ben Bernanke has declared understanding the forces behind the Great Depression is the “Holy Grail of economics”. It’s ironic. That the Fed never repeats its failure to aggressively expand the money supply in time of crisis is a key facet of the Bernanke doctrine – policy failing he asserts was a primary contributor to Depression-era financial and economic collapse. Yet this era’s unprecedented period of monetary stimulus is fundamental to current financial, economic, social and geopolitical instabilities.

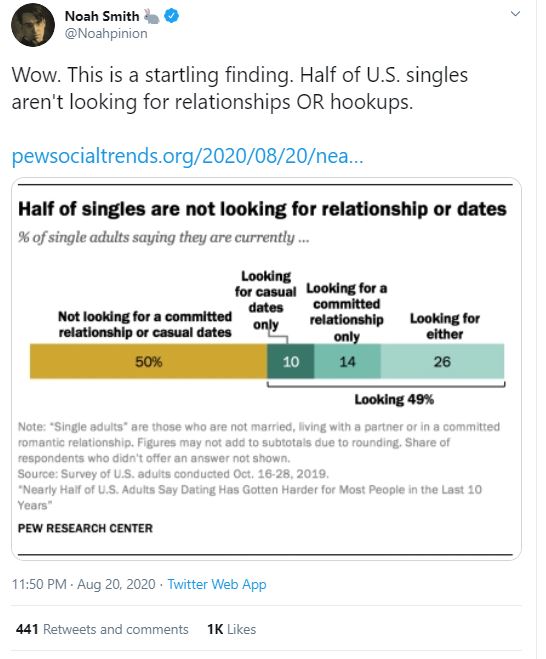

August 18 – Bloomberg (Craig Torres): “The concentration of market power in a handful of companies lies behind several disturbing trends in the U.S. economy, like the deepening of inequality and financial instability, two Federal Reserve Board economists say in a new paper. Isabel Cairo and Jae Sim identify a decline in competition, with large firms controlling more of their markets, as a common cause in a series of important shifts over the last four decades. Those include a fall in labor share, or the chunk of output that goes to workers, even as corporate profits increased; and a surge in wealth and income inequality, as the net worth of the top 5% of households almost tripled between 1983 and 2016. This fueled financial risks and higher leverage, the economists say, as poorer households borrowed to make ends meet while richer ones shoveled their wealth into bonds… ‘The rise of market power of the firms may have been the driving force’ in all of these trends, Cairo and Sim write in the paper.”

My analytical framework’s “money” and Credit focus is at times lacking in capturing non-monetary macro factors. To blame the Fed and global central banks for all that ails the world (while a valid starting point) represents a too simplified view of complex dynamics. To be sure, technological innovation and advancement along with “globalization” continue to exert momentous influence – arguably at an accelerated pace. Indeed, analysis with technological and globalization trends at its focal point could offer a plausible explanation of many macro developments – to the exclusion of policymaking and finance. As the above Fed research asserts, it is increasingly tempting to deflect blame for inequality upon monopoly power.

Isabel Cairo and Jae Sim’s Fed research paper, “Market Power, Inequality, and Financial Instability,”is a technical research piece: “A few secular trends have emerged in the U.S. economy over the last four decades… First, real wage growth has stagnated behind productivity growth over the last four decades and, as a result, the labor income share has steadily declined… Second, the before-tax profit share of U.S. corporations has shown a dramatic increase in the last few decades… Third, income inequality has been exacerbated over the last four decades… Fourth, wealth inequality has also been exacerbated during the last four decades… Finally, the rising household sector leverage has been coupled with rising financial instability…” “We develop a real business cycle model and show that the rise of market power of the firms in both product and labor markets over the last four decades can generate all of these secular trends.”

“In this paper, we quantitatively investigate the role of rising firms’ market power in both product and labor markets in explaining the six secular trends. In so doing, we are inspired by Kalecki (1971), who… predicted that the market power of the firms would increase over time and consequently, labor share would fall in the long-run.”

Understandably, Amazon lost money in its initial years. Losses mounted steadily from 1995, jumping to $720 million by 1999, $1.4 billion in the year 2000 and $567 million in 2001. The company posted a 2003 profit of $35 million on revenues of $5.3bn. Net Income jumped to $589 million in 2004 (pre-tax $365 million), earnings not exceeded until 2008’s $645 million (on revenues of $19.2bn). Amazon reported Net Income last year of $13.18 billion on Revenues of $280.5bn.

What impact did loose monetary policies have on Amazon’s evolution to an online retail juggernaut, crushing traditional retailers and online competitors alike? Enjoying limitless access to virtually free finance, there were no constraints on investment spending (or acquisitions). And as competitors increasingly struggled to retain profitability and affordable finance, there was nothing holding back Amazon’s rein of dominance.

Tesla’s stock price closed the week at $2,050, up almost 400% y-t-d, with a market capitalization of $390 billion, exceeding the combined capitalization of five global auto heavyweights (Ford $26.7bn, GM $41.0bn, Toyota $218bn, Honda $45.3bn, and Daimler $51.8bn). Tesla reported losses of $725 million in 2016, $1.8bn in 2017, $742 million in 2018 and $629 million in 2019. After reporting cumulative profits of about $450 million over the past four quarters, Tesla’s stock currently trades with a price/earnings ratio of 895.

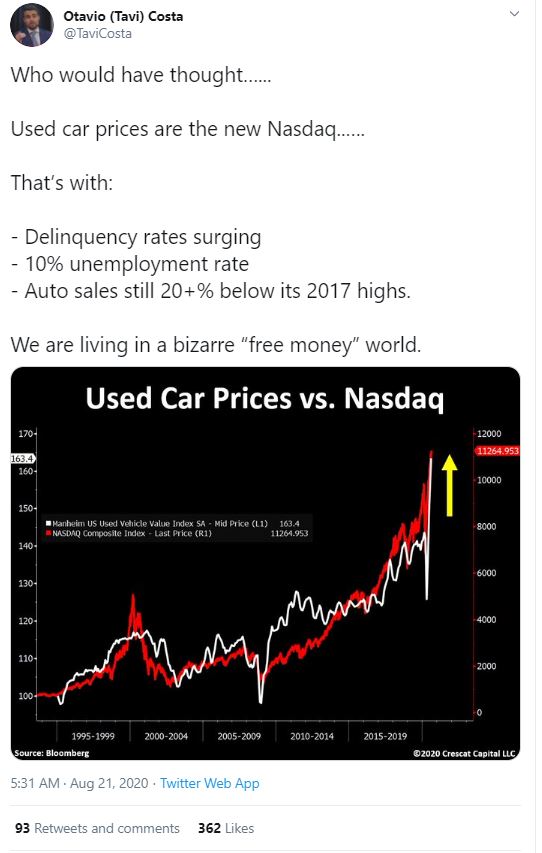

How would Tesla appear these days if not for ongoing aggressive Federal Reserve stimulus and the resulting loosest financial conditions imaginable? Would it have survived? I’m all for zero emissions vehicles – as well as a proponent for Schumpeter’s “creative destruction.” But zero rates, QE, mispriced finance and market Bubbles have created financial and economic distortions with momentous consequences. Years of ultra-cheap finance, booming securities markets, and a most elongated business cycle have created powerful industry behemoths. Pandemic crisis measures now cement monopoly power.

To be sure, whether it is Amazon, Tesla, Netflix, Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook or scores of other market darlings, a hot stock price is essential to achieving market dominance. For one, it provides a currency for acquisitions, purchases that often include fledgling competitors. And as these companies grow increasingly dominant in both the markets and real economy, surging stock prices ensure these heavyweights attract and retain the best and brightest talent (further cementing competitive advantage).

There is today no more powerful factor in exacerbating inequality than the stock market. A position (with stock grants) at one of the hundreds of market darlings is today a ticket to extraordinary riches. While tens of millions have lost their jobs and financial security over recent months, those fortunate to be riding the bull market wave have enjoyed spectacular wealth gains.

August 20 – Bloomberg (Liz Capo McCormick): “The unprecedented speed and scale of the Federal Reserve’s buying of Treasuries and mortgage debt to aid a severely impaired bond market has accomplished that without raising the specter of moral hazard, Federal Reserve Bank of New York researchers wrote… Pandemic-sparked volatility in March caused liquidity in the world’s biggest bond market to plunge to its worst since the 2008 financial crisis. The Fed responded with purchases of Treasuries and mortgage securities that peaked at more than $100 billion a day combined. It’s still soaking up about $80 billion of Treasuries and at least $40 billion of mortgage securities a month, and some bond veterans warn that the central bank’s involvement in the market could potentially be encouraging risky behavior, such as excessive borrowing. But a post… in the New York Fed’s Liberty Street blog argued against that. ‘The magnitude of the Desk’s purchase program in 2020 ‘to support the smooth functioning’ of the Treasury and agency MBS markets marked those purchases as highly unusual,’ wrote Kenneth Garbade, a senior vice president in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group, and Frank Keane, a senior policy advisor. But they also say that the tool has been used before and ‘the infrequency of Federal Reserve intervention suggests that relying on the Fed on those rare occasions when markets are in extremis has not materially exacerbated moral hazard.”

The Fed’s stunning pandemic response has greatly exacerbated at least two pernicious dynamics – Inequality and Moral Hazard. Only Fed economists could argue the Federal Reserve’s crisis response measures haven’t stoked risk-taking throughout the markets (and in the real economy). Indeed, any doubt that the Fed would invoke “whatever it takes” to support the securities markets has been allayed.

It is strangely flawed analysis deserving of a response. “The magnitude of the Desk’s purchase program in 2020 ‘to support the smooth functioning’ of the Treasury and agency MBS markets marked those purchases as highly unusual. From an operational perspective the speed and size of the program were unprecedented, yet as a policy response, as the three episodes discussed here show, it was not unique.”

The Fed economists point to three episodes as evidence recent Fed crisis measures were not unique: 1) Fed purchases of $800 million of Treasuries during September 1939, at the start of WWII. 2) Several hundred million Treasury purchases in response to disorderly markets in July 1958. 3) The buying of several billion Treasury securities in May 1970, in response to disorderly markets after President Nixon announced a military escalation with large-scale operations in Cambodia – along with anti-war protests and the Kent State tragedy. The analysis concludes with a bold assertion: “…The infrequency of Federal Reserve intervention suggests that relying on the Fed on those rare occasions when markets are in extremis has not materially exacerbated moral hazard.”

Arguably, the three highlighted historical interventions have little or no bearing whatsoever on today’s Moral Hazard Quagmire.

I would point to more than three decades of serial – and escalating – market interventions and bailouts – including Greenspan’s 1987 post-crash liquidity assurances; early ‘90’s aggressive rate cuts and yield curve manipulation; 1994 GSE quasi-central bank liquidity operations; the 1995 Mexican bailout; Greenspan’s pro-markets “asymmetric” policy responses; the ’98 LTCM bailout to safeguard global derivatives markets; Bernanke’s 2002 “helicopter money” and “government printing press” speeches; the Fed’s post-tech Bubble accommodation of rapid mortgage Credit growth as the primary system reflation mechanism – and the subsequent blatant disregard for mortgage finance and housing excesses; the post-Bubble $1 TN QE program, bailouts and various extraordinary crisis measures in 2008/09; the Bernanke Fed’s coercion of savers into the debt and equities markets; Draghi’s “whatever it takes” 2012 crisis response; Bernanke’s 2013 assurance that the Fed would “push back” against any market tightening of financial conditions (i.e. market corrections); the Bernanke and Yellen Feds’ decade-long aversion to policy normalization; the Powell Fed’s abrupt market instability-induced December 2018 abandonment of policy “normalization”; the September 2019 “insurance” rate cut and QE in the face of record stock prices and generally overheated securities markets.

“Moneyness of Credit” was an analytical focus of mine during the mortgage finance Bubble period. It was a historic Moral Hazard episode, with the government-sponsored enterprises, the Treasury and Federal Reserve all contributing to the perception that federal backing insured mortgage finance would remain safe and liquid (money-like) – irrespective of the risk profile of the underlying mortgages. The view that Washington would never allow a housing (or mortgage finance) bust was fundamental to egregious risk-taking and excess (in both the Real Economy and Financial Spheres).

I coined “Moneyness of Risk Assets” in 2009 upon recognizing that Bernanke was targeting rising equities and corporate Credit markets as the primary mechanism for post-Bubble system reflation. Epic Moral Hazard was unleashed. Markets accurately assumed the Fed had taken a giant leap with respect to market intervention and support – with the greater the degree of Bubble excess the more confident the marketplace became that the Fed wouldn’t risk pulling back.

In the realm of Moral Hazard, last autumn’s “insurance” monetary stimulus was a catastrophic policy blunder. Stress was building in leveraged speculation and within global derivatives markets – air was beginning to leak from the global financial Bubble. The Fed’s aggressive measures quashed the incipient market correction and stoked only greater speculative excess. This ensured the acute market fragility that contributed to March’s near-financial meltdown.

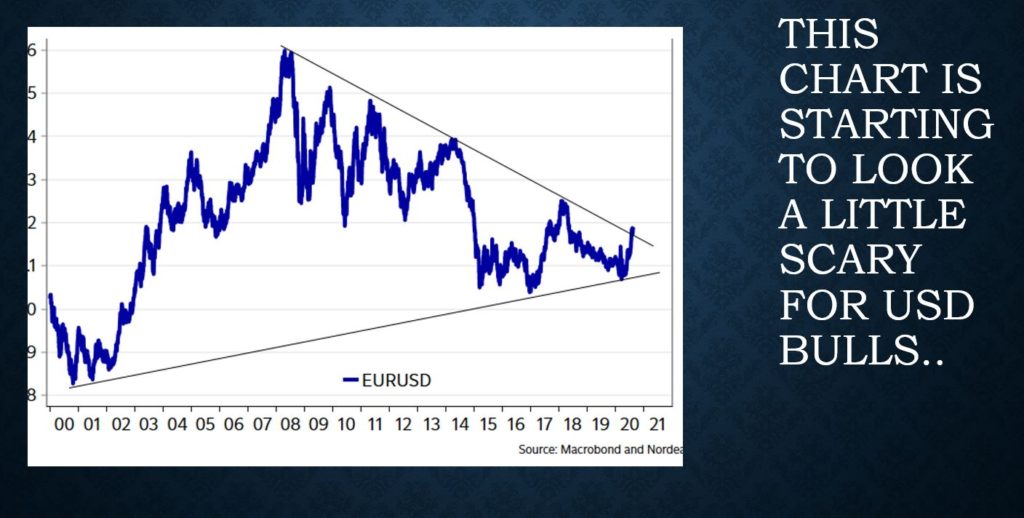

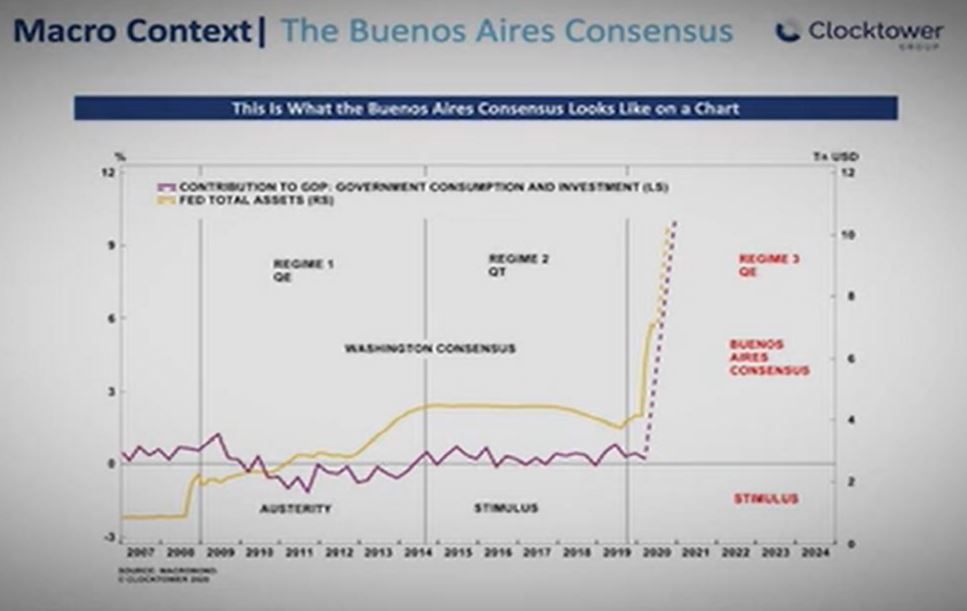

And the financial crisis spurred an unprecedented $3 TN expansion of Fed market liquidity. M2 money supply surged an unparalleled $2.9 TN in only six months, in an ongoing episode of historic Monetary Disorder. And when it comes to Moral Hazard, one cannot overstate the significance of the Fed’s giant leap to purchasing corporate bonds and even ETFs that hold junk bonds. With rates back to zero and the Fed now directly backstopping corporate Credit, “money” has flooded into perceived safe and liquid bond ETFs (in the face of the steepest economic downturn in decades). A debt issuance bonanza ensued.

Once more for posterity: “…The infrequency of Federal Reserve intervention suggests that relying on the Fed on those rare occasions when markets are in extremis has not materially exacerbated moral hazard.”

Rather than infrequent, Fed intervention has become incessant. Market “extremis” has turned commonplace. And any assertion that Fed policies have not materially exacerbated Moral Hazard completely lacks credibility. In fact, it’s foolish.

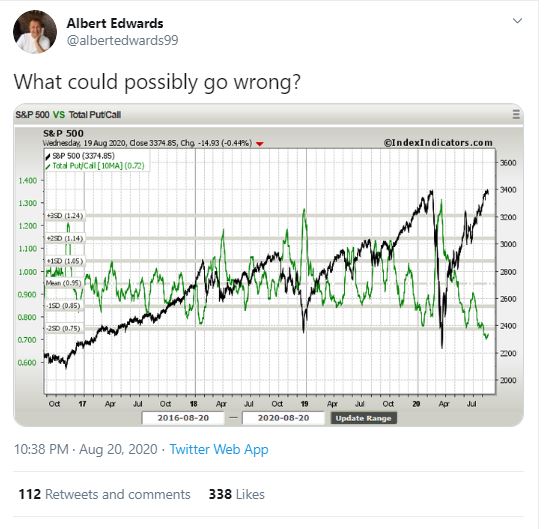

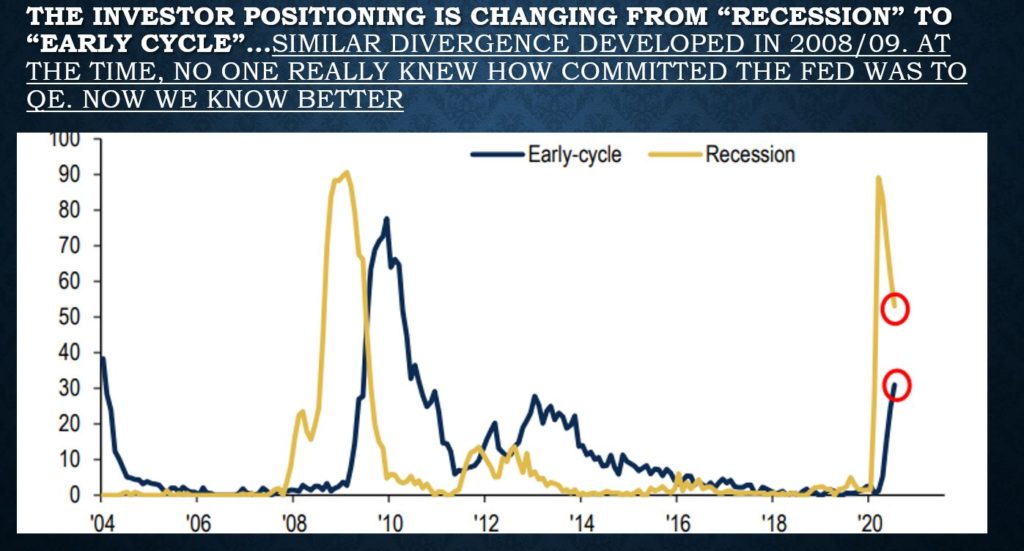

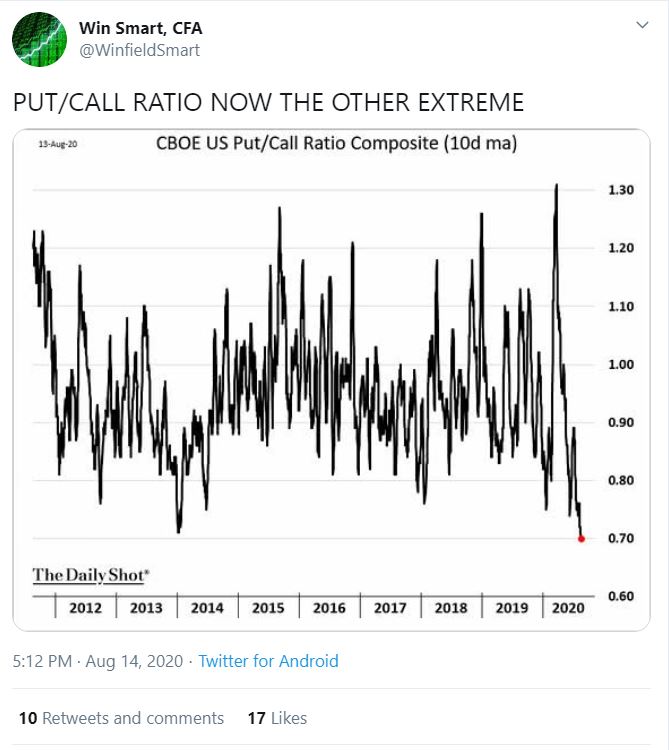

Friday afternoon from Bloomberg (Lu Wang): “Bears Are Going Extinct in Stock Market’s $13 Trillion Rebound.” “Skeptics are a dying breed in American Equities.” “Going by the short positions of hedge funds, resistance to rising prices is the lowest in 16 years… At the start of August, the median S&P 500 stock had outstanding short interest equating to just 1.8% of market capitalization, the lowest level since at least 2004…” “At 26 times forecast earnings, the S&P 500 was trading at the highest multiple since the dot-com era.” “Consider the internet frenzy 20 years ago. Back then, large speculators, mostly hedge funds, were net short on S&P 500 futures in all but five weeks in 1998 and 1999. Those mostly losing bets were completely squeezed out in 2000. That’s when the crash came.”

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2020/08/weekly-commentary-moral-hazard-quagmire.html