In a CBB from a decade or so ago, I noted that at the commencement of WWII President Roosevelt marshaled an agreement from the major warring parties to avoid the bombing of civilian targets. It was not long, however, before civilians living near military installations were considered unfortunate collateral damage. And so began the incremental abandonment of the principle of safeguarding innocent noncombatants. By the end of the war, there were no limits – nothing too outrageous or deplorable: population centers, viewed strategically as even more valuable than military targets, were under unrelenting brutal bombardment. Hiroshima and Nagasaki suffered nuclear devastation.

“Money printing” and fiscal borrowing/spending viewed as unconscionable prior to 2008 are these days easily justified. The “nuclear option” is readily accepted as a mainstream policy response. A Wall Street economist appearing on Bloomberg even posited the current crisis is worse than World War II.

To challenge monetary and fiscal stimulus is almost tantamount to being unAmerican. After all, tens of millions of American citizens are hurting – millions of small businesses near the breaking point. They are deserving of support in these circumstances. Yet I don’t want to lose focus on analyzing and chronicling ongoing catastrophic policy failure. COVID-19 greatly muddies the analytical waters.

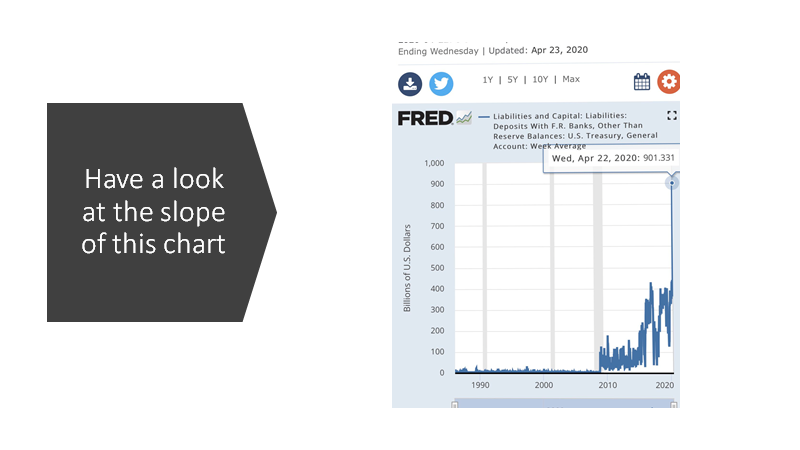

Federal Reserve Credit jumped another $146bn last week to $6.598 TN, pushing the eight-week gain to a staggering $2.453 TN. M2 “money supply” rose $365bn, with an eight-week rise of $1.727 TN. Institutional Money Fund Assets (not included in M2) rose another $76bn, boosting the eight-week expansion to $921bn.

The Fed this week expanded its new “main street” lending facility, raising limits to include companies with up to 15,000 employees and $5.0 billion in revenues. Our central bank, as well, broadened terms for its state and local government financing vehicle to include counties as small as 500,000 (down from 2 million) and cities of 250,000 (reduced from 1 million).

From the WSJ (Nick Timiraos and Jon Hilsenrath): “The Federal Reserve is redefining central banking. By lending widely to businesses, states and cities in its effort to insulate the U.S. economy from the coronavirus pandemic, it is breaking century-old taboos about who gets money from the central bank in a crisis, on what terms, and what risks it will take about getting that money back.” The article quoted Chairman Powell: “None of us has the luxury of choosing our challenges; fate and history provide them for us. Our job is to meet the tests we are presented.”

There has traditionally been an unwritten agreement – an understanding borne from historical hardship – that central banks would never resort to flagrant monetary inflation. Risk to “innocent civilians” would be much too great. “Open letters” challenged the Fed’s foray into QE, including one from 2010 signed by a group of leading economists: “We believe the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called ‘quantitative easing’) should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances. The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.”

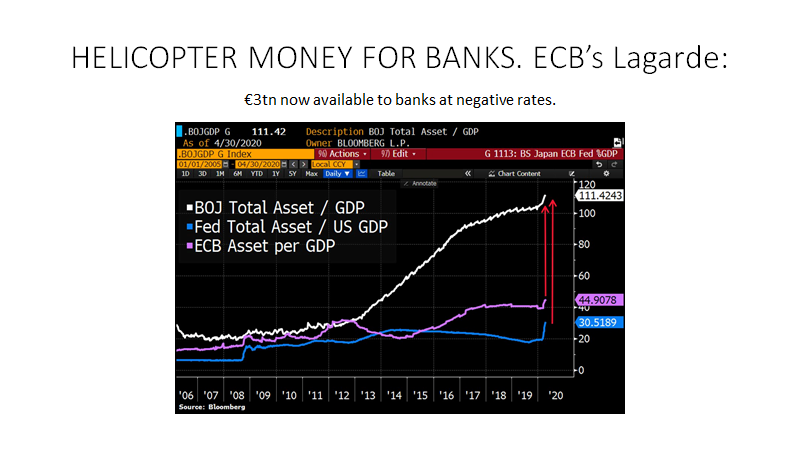

QE was to be a temporary crisis-management tool, employed to respond to the “worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.” The initial Trillion from late-2008 was to be reversed, returning the Fed’s balance sheet back near the pre-crisis $1.0 Trillion level. Somehow, QE was employed in 2019, with stocks at record highs and unemployment at 60-year lows. Last year’s monetary fiasco foreshadowed the 2020 nuclear option – a couple Trillion in a couple months. At this point, it’s gone so far beyond anything thought possible with “helicopter money” or even MMT stimulus. Don’t hold your breath awaiting “open letters” of protest. A Fed balance sheet briskly on its way to $10 TN seems just fine to most.

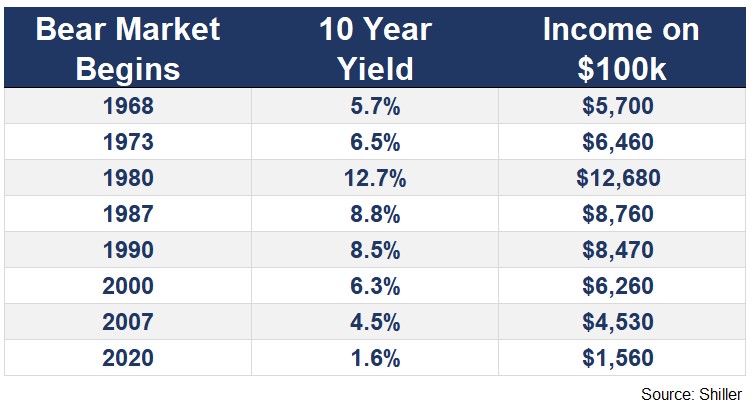

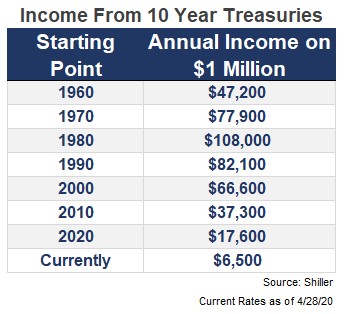

The Fed cut rates to zero (0-0.25%) in December 2008. The Fed then waited a full seven years for a single little “baby step” 25 bps increase. Nine years from the slashing to zero, rates were still only 1.25% (to 1.5%), before peaking at a paltry 2.25% (to 2.50%) with the Powell Fed’s final 25 bps increase in December 2018. Going into the 2008 crisis at less than $900 billion, the Fed’s balance sheet was still at $3.7 TN as of August 2019 (down from peak $4.5TN).

The Fed’s failure to retreat from aggressive monetary stimulus (aka “removing the punch bowl”) was a critical policy blunder that promoted destructive financial and economic excess. And in an unamusing Groundhogs Day dynamic, we are to believe that the current crisis will be resolved by only more egregious volumes of Fed liquidity and “loose money”. As master of the obvious, I will state categorically: “It’s not going to work.”

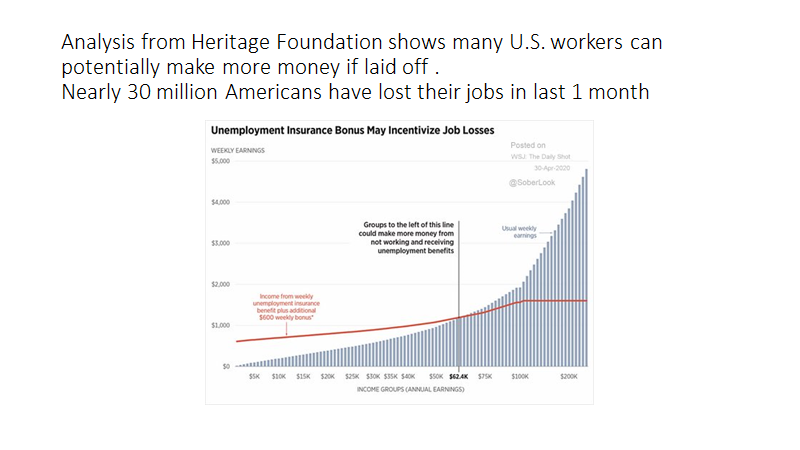

A question from Bloomberg’s Steve Matthews during Chairman Powell’s post-meeting press conference: “Do you worry that this recession is going to fall hardest on those workers who’ve struggled and just got job gains in the last year or two, and that it may take years from now before there are opportunities for them again?”

Powell: “…We were in a place, only two months ago, we were well into, beginning the second half of the 11th year is where we were. And every reason to think that it was ongoing. We were hearing from minority, low and moderate income in minority communities that this was the best labor market they’d seen in their lifetime. All the data supported that as well. And it is heartbreaking, frankly, to see that all threatened now. All the more need for our urgent response and, also, that of Congress, which has been urgent and large, and to do what we can to avoid longer run damage to the economy which is what I mentioned earlier. This is an exogenous event that, you know, it happened to us. It wasn’t because there was something wrong with the economy. And I think it is important that we do everything we can to avoid that longer-run damage and try to get back to where we were because I do very much have that concern.”

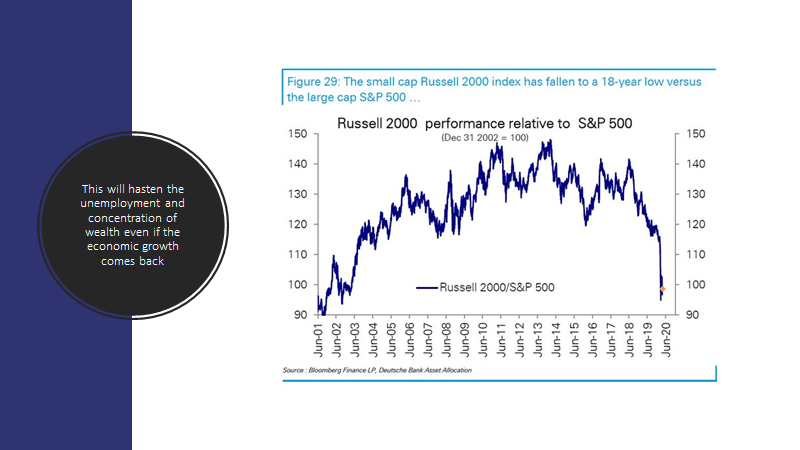

My comment: I understand the Fed’s attention to “community outreach” and its PR focus on minorities and low-income workers. Yet not even Trillions of lip service will change the reality that the Fed’s securities market policy focus promotes inequality and divisiveness. At its roots, QE is a mechanism of wealth redistribution. Zero rates transfer wealth from savers to borrowers and speculators.

Moreover, there are myriad costs associated with central banks nullifying the business cycle. The toll the unfolding crisis will inflict upon minority and low-income families will be horrendous. Federal Reserve policies of unrelenting monetary stimulus and market intervention ensure an especially problematic downturn. The business cycle is absolutely essential to the functioning of capitalistic systems. Policymaker intolerance for even mild market and economic corrections promotes cumulative excess and distortions that will culminate in extraordinarily deep and painful busts. I viewed chair Yellen’s employment focus as convenient justification and rationalization for delays to the start of policy “normalization.” Boom and bust dynamics do no favors for minorities and the working class. Monetary and financial stability should have been the Fed’s top priority. QE, low rates and market backstops reinforce instability and latent fragility.

The Associated Press’s Chris Rugaber: “You did talk about potential loss of skills over time. So, are you worried about structural changes in job markets that would keep unemployment high and, therefore, potentially beyond the ability of the Fed to do anything about, which was something that was debated, as you know, after the last recession?”

Powell: “So, in terms of the labor market, the risk of damage to people’s skills and their careers and their lives is a function of time to some extent. So, the longer one is unemployed, the harder it gets, I think, and we’ve probably all seen this in our lives, the harder it is to get back into the workforce and get back to where you were, if you ever do get back to where you were. So… longer and deeper downturns have had, have left more of a mark, generally, in that dimension with the labor force. And so, that’s why, as I mentioned, that’s why the urgency in doing what we can to prevent that longer-run damage.”

My comment: Central banks have for way too long encouraged the notion of deflation as the principal risk. I have argued Bubbles were instead the overarching systemic risk. Central bankers (along with Wall Street) have asserted that aggressive monetary stimulus has been necessary to counter deflationary risks. But if Bubbles were indeed the prevailing risk, this added stimulus would undoubtedly promote only greater maladjustment, systemic risk and fragility. After already contributing to inequality and divisiveness, monetary policymaking now places trust in the institution of the Federal Reserve in jeopardy. Flawed doctrine and a string of recurring missteps have ensured the worst of possible outcomes: a deep and prolonged downturn within a backdrop of heightened social and political instability.

Politico’s Victoria Guida: “…More broadly, you mentioned earlier this year that the federal debt was on an unsustainable path. And I was just wondering, for Republicans that are starting to get worried about how much fiscal spending they’re having to do in this crisis, you know, whether that should be a concern for them?

Powell: “In terms of fiscal concern…, for many years, I’ve been, before the Fed, I have long time been an advocate for the need for the United States to return to a sustainable path from a fiscal perspective at the federal level. We have not been on such a path for some time which just means that the debt is growing faster than the economy. This is not the time to act on those concerns. This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to do what we can to support the economy and try to get through this with as little damage to the longer run productive capacity of the economy as possible. The time will come, again, and reasonably soon, I think, where we can think about a long-term way to get our fiscal house in order. And we absolutely need to do that. But this is not the time to be, in my personal view, this is not the time to let that concern, which is a very serious concern, but to let that get in the way of us winning this battle…”

My comment: We’re in the endgame. There will be no turning back on either massive monetary or fiscal stimulus. Not surprisingly, Congress is already contemplating an additional Trillion dollars of spending. The floodgates have been flung wide-open, and at this point it will prove troublesome to ration stimulus. Meanwhile, deeply maladjusted market and economic structure will dictate unrelenting stimulus measures.

I would add that last year’s reckless Trillion dollar federal deficit was the upshot of years of experimental monetary policy. There was but one mechanism with the power to inhibit Washington profligacy: market discipline (i.e. higher Treasury yields). But market discipline was one of the great sacrifices to the Gods of QE and New Age monetary management. Stating that the Fed has been complicit in Washington running massive deficits (even throughout a market and economic boom period) is not strong enough.

Bloomberg’s Michael McKee: “And I know you said that this isn’t the time to worry about moral hazard, but do you worry, with the size of stimulus that you and the Congress are putting into the economy, there could be financial stability problems if this goes along?”

Powell: “In terms of the markets…, our concern is that they be working. We’re not focused on the level of asset prices in particular, it’s just markets are trying to price in something that is so uncertain as to be unknowable which is the path of this virus globally and its effect on the economy. And that’s very, very hard to do. That’s why you see volatility the way it’s been, market reacting to things with a lot of volatility. But… what we’re trying to assure really, is that the market is working. The market is assessing risks, lenders are lending, borrowers are borrowing, asset prices are moving in response to events. That is really important for everybody, including… the most vulnerable among us because, if markets stop working and credit stops flowing, then you see, that’s when you see… very sharp negative, even more negative economic outcomes. So, I think our measures have supported market function pretty well. We’re going to stay very careful, carefully monitoring that. But I think it’s been good to see markets working again, particularly the flow of credit in the economy has been a positive thing as businesses have been able to build up their liquidity buffers.”

My comment: It is the nature of contemporary Bubble markets that they are only “working” when they’re inflating. We witnessed again in March how quickly selling turns disorderly – how abruptly markets turn illiquid and dislocate. There were, after all, only nine trading sessions between February 19th all-time market highs and the Fed’s March 3rd emergency rate cut.

The Fed has for years nurtured the perception that the Federal Reserve was ready to backstop the markets in the event of incipient instability. The Fed “put” became deeply embedded in the pricing of various asset markets – certainly including stocks, corporate Credit, Treasuries, structured finance and derivatives. But this financial structure turns unsupportable the moment markets begin questioning the capacity of central banks to sustain inflated prices.

We observed the Fed being “trapped” dynamic in action: Market Bubbles had inflated to unparalleled extremes. When collapse began in earnest, unprecedented liquidity injections and interventions were required to reverse the panic. But this liquidity was then available to fuel disorderly markets on the upside, setting the stage for only more instability going forward. Fed officials are surely delighted their measures are proving instrumental in what will be record debt sales (Treasuries and corporates). But do today’s market yields make any sense heading into a major economic downturn with unprecedented debt and deficits? The Fed can claim it doesn’t focus on the level of asset prices, but the reality is the Fed is trapped in policies meant to sustain highly elevated asset markets.

Listening to Bloomberg Television Wednesday ahead of the Fed’s policy statement, I sat in disbelief at what I was hearing: one of our nation’s leading economists speaking utter nonsense. There is a long list of individuals that should have some explaining to do when this all blows up.

Bloomberg’s Tom Keene: “In the field of economics, there are people that are always excellent at mathematics and then there’s the truly excellent. I spoke with Randall Kroszner of Chicago and the Booth School earlier today – he’s one of those people. And another one is Narayana Kocherlakota, of course, the President of the Minneapolis Fed and now at the University of Rochester. He has been extremely aggressive about a Fed that needs a different and better dynamic… You have said that this Fed must be more aggressive. What is the next step for Chairman Powell?”

Kocherlakota: “I think that the Fed should really contemplate going negative with interest rates. I think that would send a powerful message about their willingness to be supportive of their price stability and employment mandates. Obviously, there’s a limited amount of room that you can go negative, because eventually banks and others will substitute into cash. But I think there is some room to go negative – 25, 50 bps below zero – and that makes all your other tools more effective – the forward guidance we’re going to see at some point down the road, asset purchases and yield curve control – all that becomes more effective if you can go further below zero.”

Bloomberg’s Scarlet Fu: “We’ve seen Europe, we’ve seen Japan go further below zero and it really hasn’t done what they wanted. In Japan’s case, the country then moved to yield curve control. We know the Federal Reserve has telegraphed yield curve control as an option, what’s the risk from the Fed just moving to targeting yields now and skipping over going to negative interest rates?”

Kocherlakota: “The risk, Scarlet, is you’re not doing enough. I think the Fed statement is exactly right. The ongoing public health crisis will weigh heavily on economic activity in the near-term – and poses considerable risk to the outlook over the medium-term… You want to throw every tool you got available at that. I’m not saying I’m opposed to yield curve control – I’m absolutely not. But I think going negative with interest rates is going to make that tool even more powerful – more effective than simply rolling it out on its own.”

Keene: “One of the great themes here… and this goes to the late Marvin Goodfriend of Carnegie Mellon, is the amount of negative interest rates. Ken Rogoff at Harvard also addressed it in his glorious book, ‘The Curse of Cash’. OK, so we tweak it a quarter point, a little bit here, a little bit here. Really, do we need to experiment with a boldness that forces the banking system into new actions?”

Kocherlakota: “One of the roles of economists like myself that are in academia, you mentioned Ken and Marvin who lead the way on this, is to really try to push us into a much better place. I really believe that fifty years from now people are going to look back – economists are going to look back – as the existence of cash much like we look back at the gold standard. We look back at the gold standard as a period which really hamstrung monetary policy and created huge amounts of unemployment as a result during the Great Depression. People are going to look back at the existence of cash and the zero lower bound – the inability to go much below zero with interest rates – in the same way, hamstringing the ability of central banks to provide sufficient support to the economy – and thereby creating excessive unemployment and robbing people of their jobs.”

Fu: “…You were out front in suggesting that the Federal Reserve cut interest rates before they actually did between meetings, I just wonder with this idea of negative interest rates are you in communication with anyone on the FOMC? Is there any slice of the members of the FOMC open to the idea of negative interest rates in any meaningful proportion?”

Kocherlakota: “I’m certainly not in communication with the FOMC, except hopefully they’re watching right now. What I learned during my time as a policymaker is that – I was a hawk for a while and then I became a dove. But I could never be dovish enough. There’s always this force within you as an economist that’s pushing you toward being a hawk – to be concerned about inflation or concerns about putting too much accommodation out there – too much monetary policy out there. What I learned at my time at the Fed was never to be concerned about that. So right now, I think the Fed is concerned about going negative. They feel that somehow that’s going to cause risk to the banking system or somehow be too much in terms of monetary policy. My own view is, and I hope I’m wrong on this, but I think they’ll learn as we have a slow recovery from where we are that they’ll have to do more. I think negative will come up… Down the road I think it will come up because I think they’ll need it.”

“The Fed must be more aggressive”? You gotta be kidding. And why such an ardent proponent of negative rates when there is little if any evidence from Europe or Japan that they are constructive? The “existence of cash” and the “zero lower bound” are the problems – similar to the gold standard? All nonsense. Our nation desperately needs some talented young, independent-minded economists to take the initiative to reform our deeply flawed economic doctrine. This week’s CBB was too heavy on quotes and light on analysis. But there was just a lot that needed to be documented.

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/