Doug Noland writes

“Money” challenged – and often confounded – economic thinkers for centuries. It functions as both as a “medium of exchange” and “unit of account.” Simple enough. Too often the focus has been how to use money to stimulate economic activity and achieve political gains. From my perspective, money’s importance lies with its fundamental roles as a “Store of Value” and the bedrock of financial systems. Unsound money has been a root cause of a lot of turmoil throughout history – including the monetary fiasco that collapsed in 2008. Yet concerns for the soundness of contemporary “money” these days are viewed as hopelessly archaic.

My thinking on contemporary “money” has been adapted from a much earlier focus on money’s “preciousness.” Traditionally, money was precious either because it was made of or backed by gold/precious metals. It retained preciousness only so long as its quantity remained carefully contained. Throughout history, the value of “paper money” has invariably moved inversely to the quantity issued – fits and starts, enthusiasm and revulsion and, too often, a path to worthlessness.

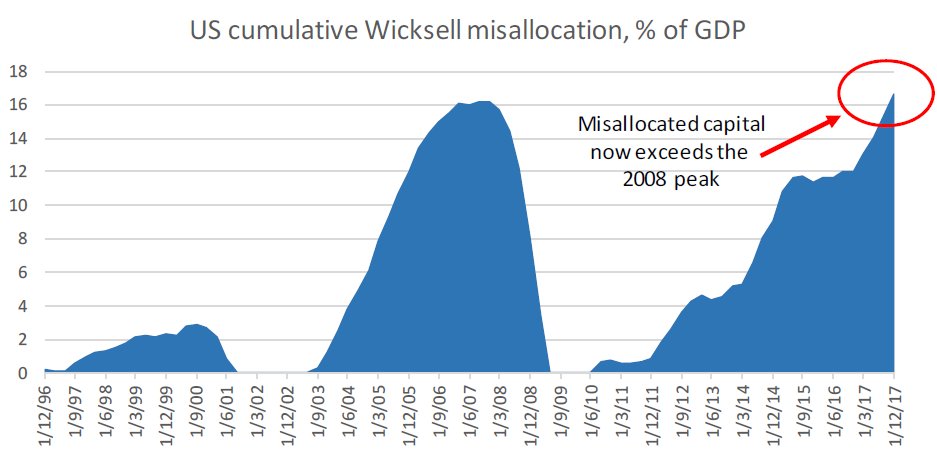

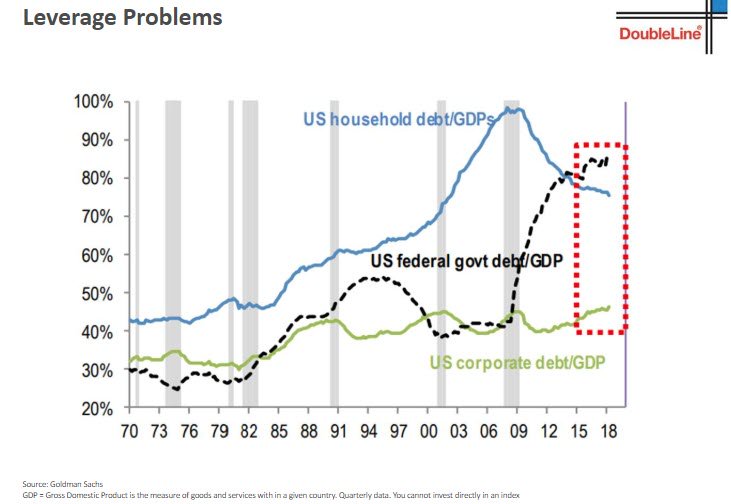

Today, “money” is largely electronic/digitized IOUs/Credit – but a special kind of Credit. Money is a perceived safe and liquid store of (nominal) value. This perception assures essentially insatiable demand. Unlimited demand creates a powerful propensity for over-issuance. Historically, monetary inflation ensured the Scourge of Inflationism. Monetary excess distorted flows to goods markets, setting in motion problematic inflationary dynamics in incomes, spending patterns and economic structure.

Despite money’s critical role within an economy, a consensus view on how best to define, monitor and manage the “money supply” escaped both the economics community and policymakers more generally. Too often, politics and ideology muddied already murky analytical waters. What is money these days, and how best to manage monetary matters? Does anyone even care – so long as the securities markets are strong?

If issues surrounding “money” aren’t confusing enough, how about this thing we refer to as “Liquidity.” As we wrap up a wild year in global markets, it would be fitting to label 2018 “The Year of Liquidity.” The year began with a bang, as liquidity inundated the emerging markets. It’s easy to forget that the Shanghai Composite jumped 5.3% in January. Brazil’s Ibovespa surged 11.1% in January and was up almost 15% by late February. The emerging market ETF (EEM) had jumped 10.5% by January 26th. South Korea’s KOSPI index rose 4.0% in January, and India’s Sensex gained almost 6%.

One could reasonably assert that “Liquidity” was in great abundance – in EM and global markets well into 2018. “Money” was flowing readily into the emerging markets, although it would be more accurate to state “finance” was flowing. Speculative Credit was most certainly expanding rapidly, as “carry trades” and a multitude of derivatives strategies funneled newly generated purchasing power into “developing” markets and economies. To be sure, the perception of a world awash in “Liquidity” ensured a problematic buildup of speculative leverage.

In general, free-flowing Credit is inherently self-reinforcing and validating (ongoing expansion supporting the perceived creditworthiness of the existing Credit structure) – hence unstable. Credit for securities speculation – speculative leveraging – is acutely unstable. The expansion of speculative Credit creates a flow of buying power, or Liquidity, that inflates securities prices and engenders only greater demand for speculative Credit. Resulting Liquidity abundance fosters confidence that markets will continue to boom skyward. “Money” everywhere.

The expansion of GSE Credit was key to the perception of Liquidity abundance early in the mortgage finance Bubble period. The expansion of GSE liabilities generated a powerful flow of buying power/Liquidity into the marketplace. Moreover, the ability and willingness to aggressively expand GSE Credit in the event of heightened market stress fostered the perception that a governmental quasi-central bank entity was available to backstop system liquidity when needed. By late in the cycle, a booming Credit expansion was creating such a prodigious flow of Liquidity that markets had little concern that fraud at the GSEs essentially eliminated their capacity to backstop market Liquidity.

Simplifying the analysis, we can consider four key – and interrelated – elements to market “Liquidity.” First, the actual purchasing power (i.e. deposits, money market funds, etc.) available to purchase securities. Second, the ease of availability of speculative Credit for the leveraging of securities. Third, the willingness and capacity of market-makers and operators to accumulate holdings in the face of intense selling pressure. And, fourth, the perception of Liquidity flows that could be injected into the system in the event of market instability and illiquidity risk (GSE backstop bid during the mortgage finance Bubble – and central bank QE throughout the global government finance Bubble).

M1 money supply ended last week at $3.736 TN, with M2 at $14.415 TN. M2 is a rather straightforward calculation adding Currency, Deposits (checking/saving/small time/other) and Retail Money Market Funds. The Federal Reserve in the past calculated M3, a broader measure of money (adding large time deposits, institutional money funds and repurchase agreements). Long arguing that broad “money” was analytically superior to the narrow aggregates, I nonetheless lost no sleep when the Fed discontinued publishing its M3 aggregate (still too narrow!). Our analytical frameworks should strive to incorporate the broadest view of “money,” Credit and “finance,” although the broader the view taken the more challenging the analysis.

I would posit that some time ago Liquidity completely supplanted the monetary aggregates as the key focal point of market flow analysis. Unfortunately, there is no quantity of “Liquidity” to measure and tabulate. I am not familiar with an adequate definition or even common understanding. The concept of contemporary “money” has proved highly problematic for the economics community. Yet Liquidity makes “money” appear quite straightforward. If it can’t be defined or calculated, it’s certainly not worthy of inclusion in econometric models.

Liquidity is an amalgam of real financial flows and intangible market perceptions. There is no aggregate that would signal whether Liquidity is either expanding or contracting. Even if overall Liquidity was viewed as either abundant or deficient, there would still be widely divergent Liquidity manifestations for individual sectors, markets, countries or regions. And how can seeming Liquidity overabundance so briskly transform into illiquidity?

“Money supply” was an invaluable tool for gauging system “Liquidity” back when bank liabilities (i.e. deposits) were the prevailing mechanism for money and Credit expansion. Analysis has changed profoundly with the globalized adoption of non-bank market-based Credit. I have argued that market-based Credit is highly unstable – speculative Credit perilously so. I would contend that “Liquidity” is typically steady but at times highly erratic. So long as the global Credit boom continues, speculative Credit expands, and markets remain stable, the perception of Liquidity abundance ensures ample purchasing power to sustain the bull market. But the Wildness Lies in Wait.

For years now, global central bank policies have been fundamental to the perception of uninterrupted Liquidity abundance. Chairman Bernanke’s zero rates and QE measures caused a historic flow of purchasing power (Liquidity) into stock and fixed-income funds. This evolved into a momentous shift of financial flows into “passive” risk market strategies (perceived as low-risk and, often, money-like). Ultra-low rates and the belief that central banks were backstopping market Liquidity fundamentally altered both the flow of Liquidity and, over time, the structure of the marketplace.

The flow of Trillions into ETF and other “passive” strategies changed the nature of global leveraged speculation. Not only were the leveraged speculators incentivized by near zero (and even negative) borrowing costs and confidence in the central bank Liquidity backstop, they were now emboldened by the predictability of huge “retail” flows into stock (domestic and international) and fixed-income funds. Booming flows into equities and bonds fundamentally loosened financial conditions on an unprecedented global basis.

Loose finance stoked asset inflation, booming M&A and buybacks, all conducive to economic expansion and surging corporate profits. Liquidity circulating briskly throughout both the Financial and Economic Spheres bolstered the perception of an endless Liquidity boom. Booming securities markets fueled U.S. consumption and ongoing huge trade deficits, dollar Liquidity flowing out to the world – only to be recycled right back into U.S. securities and asset markets (i.e. EM central bank purchases, hedge funds borrowing in offshore markets to leverage in U.S. securities, Chinese buying U.S. Treasuries and real estate, etc.). Meanwhile, booming global markets and the ease of “investing” passively through the ETF complex stoked unprecedented U.S. flows to global markets – once again generating a flow of global Liquidity that would be readily “recycled” back into U.S. markets.

Early CBBs introduced the concept of the “infinite multiplier effect.” Contemporary finance (largely devoid of capital and reserve requirements) left the old fractional reserve banking deposit “money multiplier” in the dust. The flow of purchasing power/Liquidity would circulate and recirculate, in the process fueling both unfettered Credit expansion and asset inflation. The global government finance Bubble period – with its zero rates, Trillions of new “money,” and central bank liquidity backstops – has seen the “infinite multiplier” at work on an unprecedented global scale. Liquidity created by the central banks, as well as through massive government debt expansion and leveraged speculation, has circulated freely on a global basis, inflating securities/asset prices, stoking economic expansion and promoting a self-reinforcing perception of endless Liquidity.

For the most part, contemporary market Liquidity is not real. It’s primarily a market perception. It’s based on the view that financial flows into markets will remain positive and, on those rare occasions when they’re not, central banks will step in and ensure “money” flows unabated into the financial markets. It’s based on confidence and faith – in contemporary central banking, in market structure, in the derivatives complex, in modern technologies and ingenuity. It’s based on the view that global Credit will continue to expand, premised on confidence that Beijing will ensure ongoing Credit expansion and that U.S. Credit is fundamentally robust. It’s based on the overarching belief that global finance is fundamentally sound, policymakers possess acumen and enlightenment, central bank power is boundless, and the global economy is on solid footing.

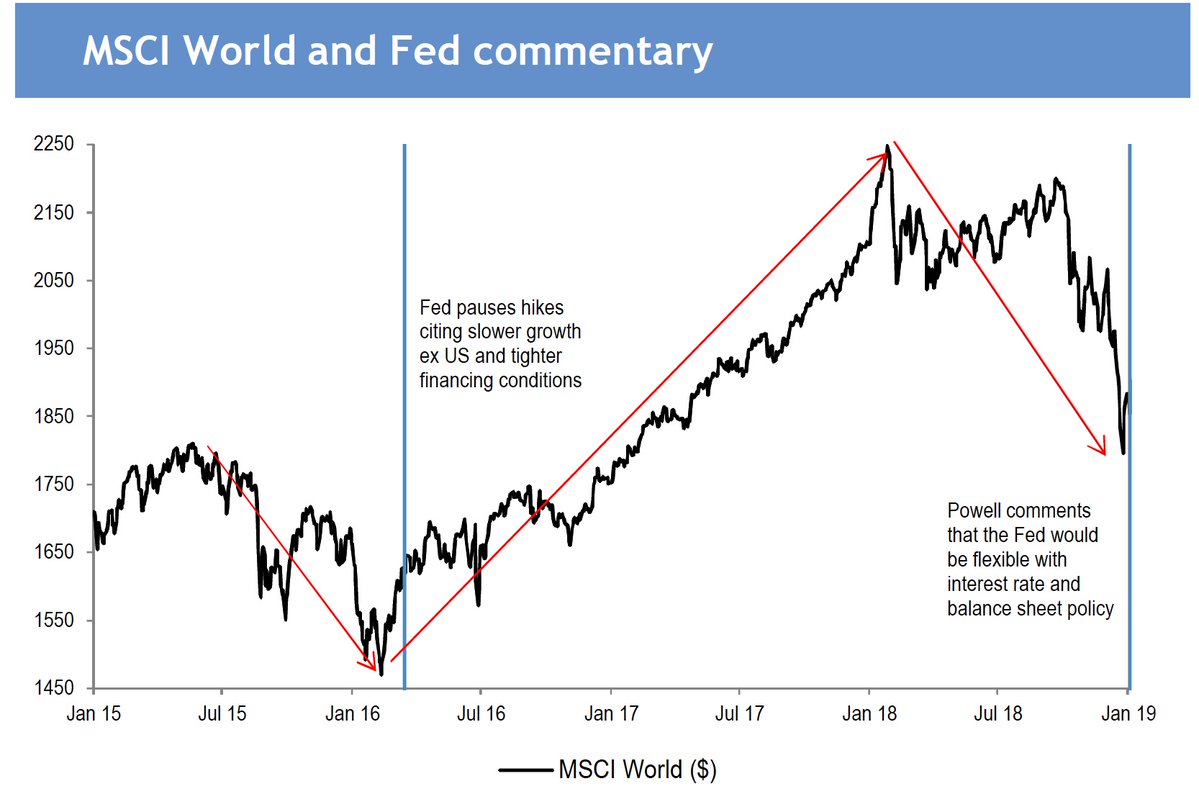

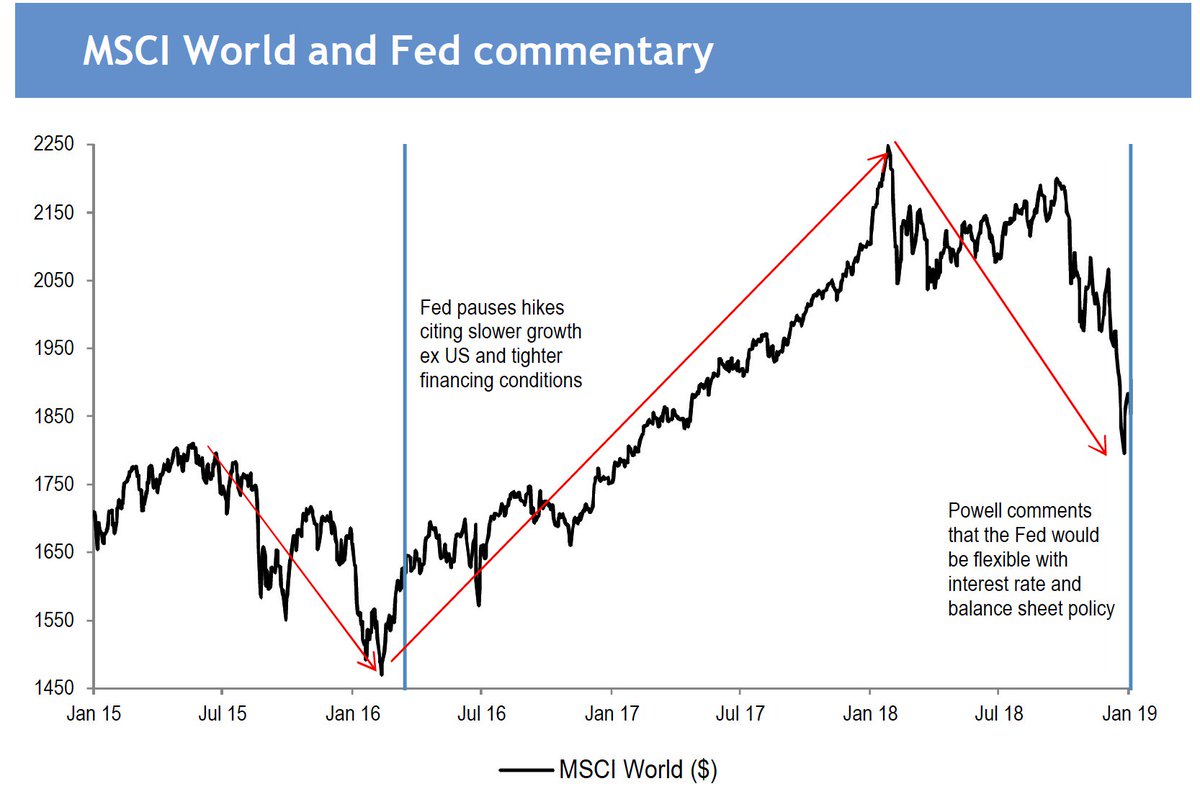

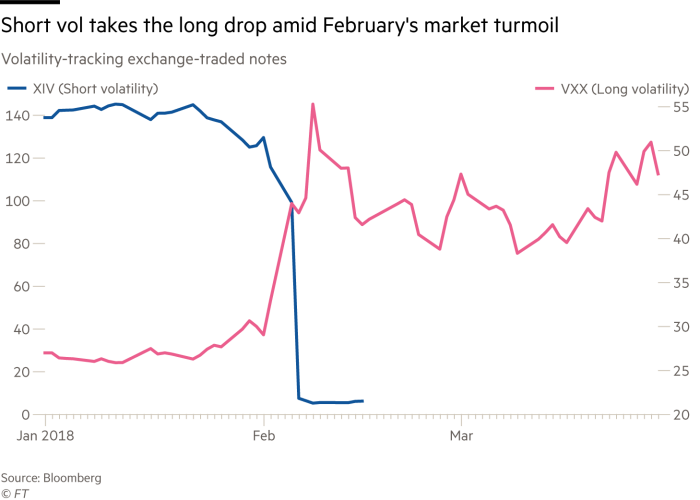

I believe the February blow-up of “short vol” strategies was a key initial crack in the global Bubble. Huge speculative excess had accumulated in a major market used for acquiring protection against market declines – writing “flood insurance” during a protracted central bank-induced drought. Abrupt market losses and illiquidity changed the risk/reward calculus for “selling” market “insurance” – reducing the supply and increasing the price of protection. Not long after, indications of fledgling risk aversion began to beset the global “Periphery.” EM Liquidity began to wane, an especially problematic dynamic following a speculative blow-off period. As EM flows reversed, de-risking/deleveraging dynamics took hold. Liquidity that seemed so abundant early in the year suddenly disappeared, replaced by faltering markets, dislocation and fear of expanding market illiquidity throughout the “Periphery.”

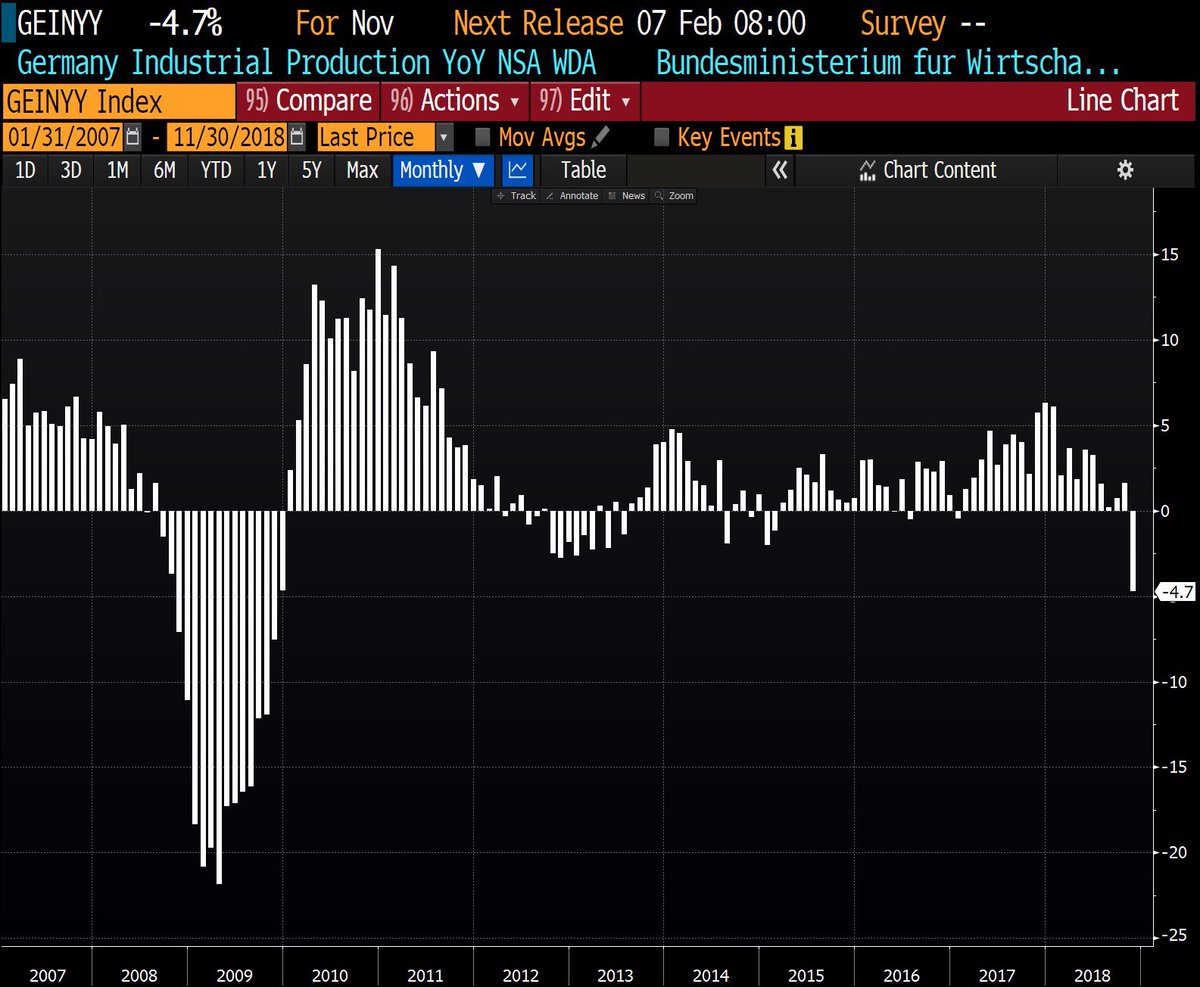

On a global basis, the Liquidity backdrop had changed momentously. For the first time in several years, a significant de-risking/deleveraging dynamic was unfolding without the benefit of huge central bank QE liquidity injections. Rapid currency collapses in Turkey and Argentina signaled a critical global Liquidity inflection point. And as de-risking/deleveraging gained momentum, Contagion became a major concern. China and Asia, the epicenter of Liquidity excesses over this cycle, saw their currencies, equities and bonds fall under significant pressure. Dollar-denominated debt, having so flourished during Liquidity abundance, was suddenly facing sinking prices and Liquidity issues. The shifting Liquidity backdrop was also manifesting in the colossal international derivatives markets (i.e. currency, swaps and fixed-income).

Market perceptions with regard to international Liquidity changed meaningfully. The same could not be said for the U.S. If anything, expectations for ongoing Liquidity abundance became only more deeply ingrained. Keep in mind that the Federal Reserve concluded QE operations in 2014. With the bull market having not missed a beat, it was widely believed that QE was irrelevant for the U.S. Not appreciated was the major role QE was having on international Liquidity, with “money” created by the ECB, BOJ and others finding its way into U.S. securities markets and the American economy. This year’s instability at the “Periphery” then initially exacerbated flows to “Core” U.S. markets, pushing already highly speculative markets into Melt-Up Dynamics.

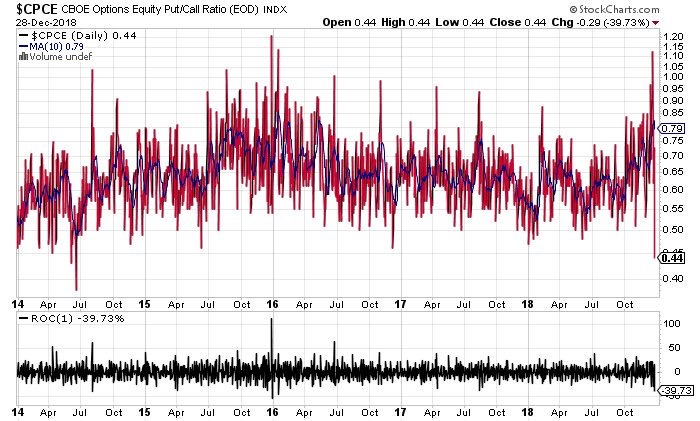

From a Liquidity perspective, speculative blow-offs are highly problematic. A bout of manic buying and leveraging culminates in highly elevated and unsustainable prices and financial flows. The perception of Liquidity abundance sows the seeds of its own destruction. When prices inevitably reverse, the onset of de-risking/deleveraging dynamics ensures a highly problematic Liquidity environment.

When the Crowd is fully on board, who is left to buy? When the leveraged speculating community reverses course, who but central banks have the capacity to accommodate deleveraging? If a significant segment of the marketplace moves to hedge market risk, where is the wherewithal to shoulder such risk? And let’s not overlook the critical issue of market risk shifting to speculators and traders expecting to dynamically-hedge option risk written/sold in the marketplace (planning, when necessary, to establish short positions in a declining marketplace). Current Market Structure ensures serious Liquidity issues upon the inevitable bursting of speculative Bubbles. Who wants to get in front of the algos?

Progressively more reckless central bank measures over the past decade have been necessary to promote the perception of ample and sustainable Liquidity. But with Crisis Dynamics having recently afflicted the “Core,” it is difficult for me not to see a Liquidity environment fundamentally altered. Confidence has taken a significant hit. I believe the leveraged speculating community has been impaired, with outflows and general risk aversion ensuring ongoing de-risking/deleveraging. Similarly, with confidence in “passive” (stock, fixed-income, international) ETF strategies now badly shaken, it is difficult to envisage a return to booming industry inflows. And with derivatives players stung by abrupt market losses and a spike in volatility (option premiums), I expect we’ve passed a critical inflection point in the pricing and availability of market protection.

The backdrop points to an inhospitable Liquidity backdrop. Serious market structural issues have bubbled to the surface, issues market participants either haven’t appreciated or simply believed would readily rectify by central banks before confidence was impacted. The orientation of powerful financial flows has been upset. Hedging and derivatives markets have dislocated. The great fallacy of “moneyness” for risky stocks, bonds and derivatives is being laid bare.

Importantly, I view speculative Credit as the marginal source of global Liquidity. I believe a historic Bubble in securities and derivatives-related Credit has been pierced. This Bubble was fueled by years of zero/negative rates and Trillions of central bank liquidity. As we saw this week, bear market rallies tend to be ferocious. And when a short squeeze and unwind of hedges is in play, surging prices will spur hope the sell-off has run its course and that Liquidity has returned to the markets.

It’s just not going to be that simple. Global markets face serious structural issues years and decades in the making. Hopefully markets can avoid crashes and make necessary adjustments over an extended period of time. For a while now, I’ve feared a scenario where illiquidity becomes a systemic global issue. From closely analyzing previous booms and bust episodes, things often prove even worse than I suspect.

Read Full article below

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2018/12/weekly-commentary-thoughts-on-liquidity.html